[There have been daily protests in Quebec for over a 100 days by hundreds of thousands of people. Starting over steep increases in student fees/tuition, accelerated by the citizen response to bill 78 which attempted to force students to get permits for any march over 50 people (and fines of 7,000 for student leaders and at least 25,000 for student groups that didn't do this), it has now become a broad based public protest of citizens (one nights march was app. 400,000 people). Watch this five minute video and see something amazing -- I think it is beautiful and ask myself, why does the Canadian government fear it ......? ]

by Jeremie Battaglia

More reports:

Riley Sparks: Large, peaceful night protest after talks break down: 'I hope it’ll go all summer'

"My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel--it is, above all, to make you see." -- Joseph Conrad (1897)

Wednesday, May 30, 2012

Jim McGovern: Rescuing "We the People"

Rescuing 'We, the People'

by Representative Jim McGovern (MA)

Huffington Post

Defenders of the Supreme Court decision in Citizens United and the ascendant corporate rights doctrine that underlies it must be getting nervous.

Why else would George Will resort to arguing, as he so outrageously does ("Taking a scythe to the Bill of Rights", May 6) that the bipartisan People's Rights Amendment I have introduced in the House is "comparable" to condoning infanticide?

A large majority of Americans believe that corporations exert too much influence on our daily lives and our political process. A Hart Research poll released last year found that nearly four in five (79 percent) of registered voters support passage of a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United. Resolutions calling for such an amendment have passed in several states and cities across the country. Eleven state attorneys general have written to Congress demanding action.

We are already witnessing the corrosive effects of Citizens United: an election system awash in a sea of millions of dollars in unregulated money, drowning out the voices of individual citizens. Politicians are increasingly beholden to wealthy special interests. A multi-national oil company that doesn't like a particular member of Congress can now simply write a big, undisclosed check to "Americans for Apple Pie and Puppies" and watch the negative advertisements work their magic.

But the effects of the corporate rights doctrine go far beyond campaign finance. A Vermont law to require that milk products derived from cows treated with bovine growth hormone be labeled to disclose that information was struck down as a violation of the First Amendment. A federal judge has found that tobacco companies have a free speech right that prevents the government from requiring graphic warning labels on cigarettes. A pharmaceutical corporation has claimed that their corporate speech rights protect them from FDA rules prohibiting the marketing of a drug for "off-label" uses.

As Justice Stevens rightly noted in his dissent in Citizens United (and contrary to what Mr. Will would have us believe), the majority ruling was "a radical departure from what has been settled First Amendment Law." These corporate "rights" are relatively new, appearing in the last few decades. They overturn centuries of established jurisprudence and national consensus. The Supreme Court used to repeatedly affirm that the elected governments of the states and the nation could regulate corporations. Chief Justice John Marshall described the corporate entity as "an artificial being ... existing only in contemplation of law." No less an authority than James Madison viewed corporations as "a necessary evil" subject to "proper limitations and guards." Thomas Jefferson wished to "crush in its birth the aristocracy of our moneyed corporations, which dare already to challenge our government to a trial of strength and bid defiance to the laws of our country."

To Read the Rest of the Commentary

by Representative Jim McGovern (MA)

Huffington Post

Defenders of the Supreme Court decision in Citizens United and the ascendant corporate rights doctrine that underlies it must be getting nervous.

Why else would George Will resort to arguing, as he so outrageously does ("Taking a scythe to the Bill of Rights", May 6) that the bipartisan People's Rights Amendment I have introduced in the House is "comparable" to condoning infanticide?

A large majority of Americans believe that corporations exert too much influence on our daily lives and our political process. A Hart Research poll released last year found that nearly four in five (79 percent) of registered voters support passage of a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United. Resolutions calling for such an amendment have passed in several states and cities across the country. Eleven state attorneys general have written to Congress demanding action.

We are already witnessing the corrosive effects of Citizens United: an election system awash in a sea of millions of dollars in unregulated money, drowning out the voices of individual citizens. Politicians are increasingly beholden to wealthy special interests. A multi-national oil company that doesn't like a particular member of Congress can now simply write a big, undisclosed check to "Americans for Apple Pie and Puppies" and watch the negative advertisements work their magic.

But the effects of the corporate rights doctrine go far beyond campaign finance. A Vermont law to require that milk products derived from cows treated with bovine growth hormone be labeled to disclose that information was struck down as a violation of the First Amendment. A federal judge has found that tobacco companies have a free speech right that prevents the government from requiring graphic warning labels on cigarettes. A pharmaceutical corporation has claimed that their corporate speech rights protect them from FDA rules prohibiting the marketing of a drug for "off-label" uses.

As Justice Stevens rightly noted in his dissent in Citizens United (and contrary to what Mr. Will would have us believe), the majority ruling was "a radical departure from what has been settled First Amendment Law." These corporate "rights" are relatively new, appearing in the last few decades. They overturn centuries of established jurisprudence and national consensus. The Supreme Court used to repeatedly affirm that the elected governments of the states and the nation could regulate corporations. Chief Justice John Marshall described the corporate entity as "an artificial being ... existing only in contemplation of law." No less an authority than James Madison viewed corporations as "a necessary evil" subject to "proper limitations and guards." Thomas Jefferson wished to "crush in its birth the aristocracy of our moneyed corporations, which dare already to challenge our government to a trial of strength and bid defiance to the laws of our country."

To Read the Rest of the Commentary

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

Inside Job Director Charles Ferguson: Predator Nation: Corporate Criminals, Political Corruption, and the Hijacking of America

"Inside Job" Director Charles Ferguson: Wall Street Has Turned the U.S. into a "Predatory Nation"

Democracy Now

Two years after directing the Academy Award-winning documentary, “Inside Job,” filmmaker Charles Ferguson returns with a new book, “Predator Nation: Corporate Criminals, Political Corruption, and the Hijacking of America.” Ferguson explores why no top financial executives have been jailed for their role in the nation’s worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. We also discuss Larry Summers and the revolving door between academia and Wall Street, as well as the key role Democrats have played in deregulating the financial industry. According to Ferguson, a "predatory elite" has "taken over significant portions of economic policy and of the political system, and also, unfortunately, major portions of the economics discipline."

Guest:

Charles Ferguson, the Academy Award-winning director of Inside Job, a documentary about the financial crisis. His film on the war in Iraq, No End in Sight, was nominated for an Academy Award. His new book is called Predator Nation: Corporate Criminals, Political Corruption, and the Hijacking of America.

To Watch the Interview

Part 2: “Predator Nation: Corporate Criminals, Political Corruption, and the Hijacking of America”

We continue our conversation with Charles Ferguson, director of the Oscar award-winning documentary, “Inside Job,” about the 2008 financial crisis. In his new book, “Predator Nation,” he argues “the role of Democrats has been at least as great as the role of Republicans” in causing the crisis. Ferguson notes the Clinton administration oversaw the most important financial deregulation, and since then, “we’ve seen in the Obama administration very little reform and no criminal prosecutions, and the appointment of a very large number of Wall Street executives to senior positions in the government, including some people who were directly responsible for causing significant portions of the crisis.” Ferguson also calls for raising the salaries of senior regulators and imposing stricter rules for how soon they can lobby for the private sector after leaving the public sector.

To Watch the Interview

Trailer for Inside Job

Watch Inside Job online for free at Film for Action

Democracy Now

Two years after directing the Academy Award-winning documentary, “Inside Job,” filmmaker Charles Ferguson returns with a new book, “Predator Nation: Corporate Criminals, Political Corruption, and the Hijacking of America.” Ferguson explores why no top financial executives have been jailed for their role in the nation’s worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. We also discuss Larry Summers and the revolving door between academia and Wall Street, as well as the key role Democrats have played in deregulating the financial industry. According to Ferguson, a "predatory elite" has "taken over significant portions of economic policy and of the political system, and also, unfortunately, major portions of the economics discipline."

Guest:

Charles Ferguson, the Academy Award-winning director of Inside Job, a documentary about the financial crisis. His film on the war in Iraq, No End in Sight, was nominated for an Academy Award. His new book is called Predator Nation: Corporate Criminals, Political Corruption, and the Hijacking of America.

To Watch the Interview

Part 2: “Predator Nation: Corporate Criminals, Political Corruption, and the Hijacking of America”

We continue our conversation with Charles Ferguson, director of the Oscar award-winning documentary, “Inside Job,” about the 2008 financial crisis. In his new book, “Predator Nation,” he argues “the role of Democrats has been at least as great as the role of Republicans” in causing the crisis. Ferguson notes the Clinton administration oversaw the most important financial deregulation, and since then, “we’ve seen in the Obama administration very little reform and no criminal prosecutions, and the appointment of a very large number of Wall Street executives to senior positions in the government, including some people who were directly responsible for causing significant portions of the crisis.” Ferguson also calls for raising the salaries of senior regulators and imposing stricter rules for how soon they can lobby for the private sector after leaving the public sector.

To Watch the Interview

Trailer for Inside Job

2010 Oscar Winner for Best Documentary, 'Inside Job' provides a comprehensive analysis of the global financial crisis of 2008, which at a cost over $20 trillion, caused millions of people to lose their jobs and homes in the worst recession since the Great Depression, and nearly resulted in a global financial collapse. Through exhaustive research and extensive interviews with key financial insiders, politicians, journalists, and academics, the film traces the rise of a rogue industry which has corrupted politics, regulation, and academia. It was made on location in the United States, Iceland, England, France, Singapore, and China.

Watch Inside Job online for free at Film for Action

Benjamin Shingler: Protesters finding creative ways around controversial new Quebec law

Protesters finding creative ways around controversial new Quebec law

by Benjamin Shingler

The Star

Only a day after becoming law, protesters were finding creative ways around Quebec’s controversial legislation aimed at restoring order in the province.

In an attempt to avoid hefty fines, one prominent student group took down its web page Saturday that listed all upcoming protests. Another anonymous web page with listings quickly popped up in its place — with a note discouraging people from attending.

The disclaimer is meant to evade new rules applying to protest organizers, who must provide an itinerary for demonstrations and could be held responsible for any violence.

The website also accepts submissions for future protests and suggests using software that blocks a sender’s digital trail.

Meanwhile, Montreal police were trying to figure out how to use the legislation without heightening tensions during the city’s nightly marches through the city.

Spokesman Ian Lafreniere said the force was still considering its options.

“I’ve got a lot of people working on it now,” Lafreniere said in an interview. “We don’t want to cause a commotion, we want to prevent one.”

Lafreniere said police would likely set up a website or email address where organizers could submit planned protest routes.

Bill 78 lays out strict regulations governing demonstrations of over 50 people, including having to give eight hours’ notice for details such as the protest route, the duration and the time at which they are being held.

Failure to comply could bring stiff penalties for the organizers, but the law could be difficult to enforce.

A late night protest has started in the same downtown square at 8:30 p.m. every night for nearly a month. There’s no clear organizer for the march, and the route is determined by the marchers on a street by street basis.

Still, the law says that student associations who don’t encourage their members to comply with the law could face punishment. Fines range between $7,000 and $35,000 for student leaders and between $25,000 and $125,000 for student unions or student federations.

To Read the Rest of the Article

by Benjamin Shingler

The Star

Only a day after becoming law, protesters were finding creative ways around Quebec’s controversial legislation aimed at restoring order in the province.

In an attempt to avoid hefty fines, one prominent student group took down its web page Saturday that listed all upcoming protests. Another anonymous web page with listings quickly popped up in its place — with a note discouraging people from attending.

The disclaimer is meant to evade new rules applying to protest organizers, who must provide an itinerary for demonstrations and could be held responsible for any violence.

The website also accepts submissions for future protests and suggests using software that blocks a sender’s digital trail.

Meanwhile, Montreal police were trying to figure out how to use the legislation without heightening tensions during the city’s nightly marches through the city.

Spokesman Ian Lafreniere said the force was still considering its options.

“I’ve got a lot of people working on it now,” Lafreniere said in an interview. “We don’t want to cause a commotion, we want to prevent one.”

Lafreniere said police would likely set up a website or email address where organizers could submit planned protest routes.

Bill 78 lays out strict regulations governing demonstrations of over 50 people, including having to give eight hours’ notice for details such as the protest route, the duration and the time at which they are being held.

Failure to comply could bring stiff penalties for the organizers, but the law could be difficult to enforce.

A late night protest has started in the same downtown square at 8:30 p.m. every night for nearly a month. There’s no clear organizer for the march, and the route is determined by the marchers on a street by street basis.

Still, the law says that student associations who don’t encourage their members to comply with the law could face punishment. Fines range between $7,000 and $35,000 for student leaders and between $25,000 and $125,000 for student unions or student federations.

To Read the Rest of the Article

Monday, May 28, 2012

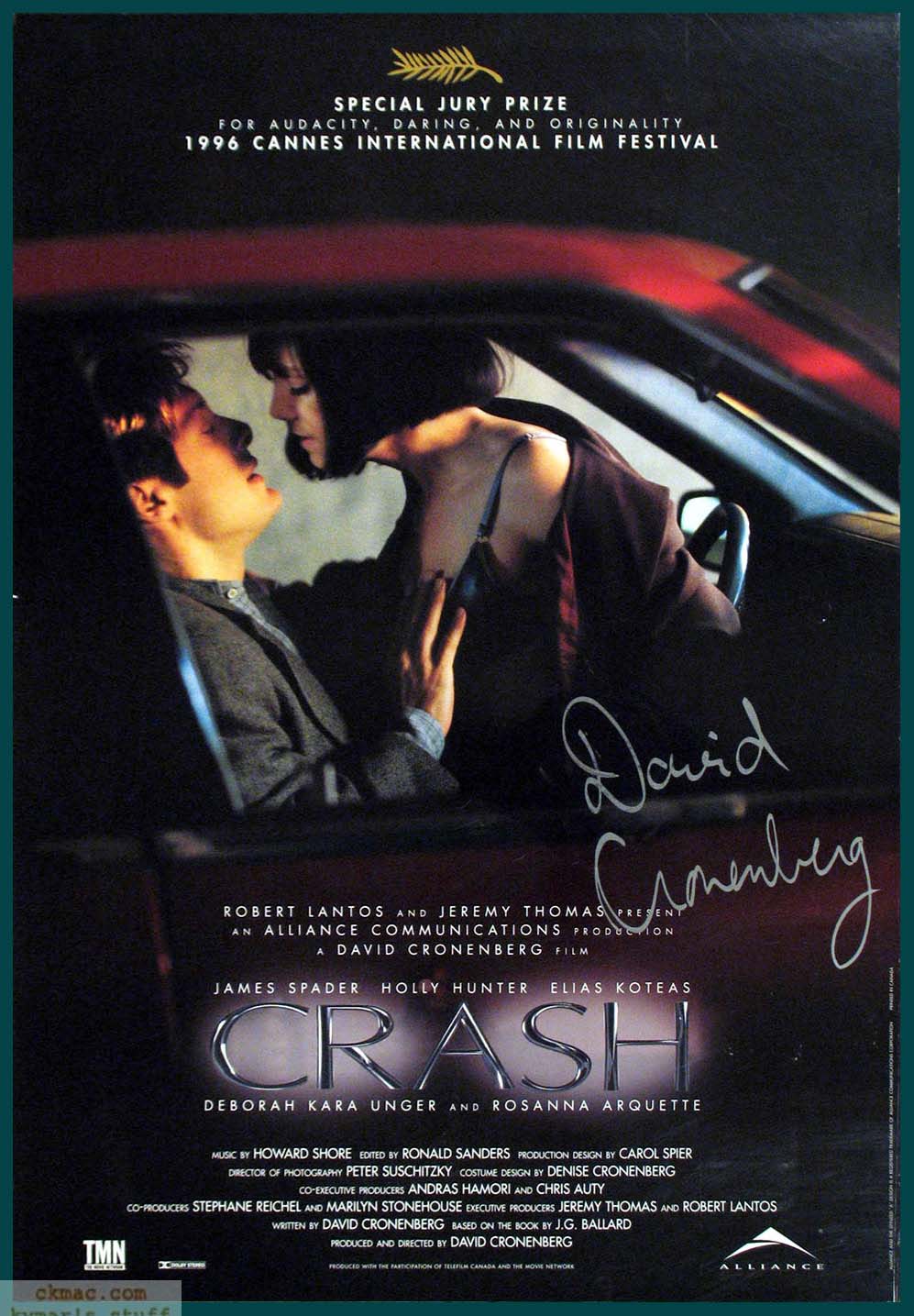

Joshua Clover: Fall and Rise

Fall and Rise

by Joshua Clover

Film Quarterly

...

But Toyota-ization too reached its limits. “Tokyo drift” describes a style of street racing where the cars are made to slide almost frictionlessly through corners, with the low impact grace of a tap dancer in a sandbox. It might just as well be a rubric for the Japanese economy of the ongoing “lost decade”—having avoided a massive economic crash, it is still unable to get back on track or restore profitability, and drifts endlessly through the long turn of late capitalism.

A consultation with reference materials suggests that Tokyo Drift was meant to be out of series and out of time; Fast Five, a less nimble film, takes place earlier. Looks like the present. So Han, a ghost of the Lost Decade, walks into a garage in the emerging economy of Brazil to take his place in the team assembled by Dom (Vin Diesel), who looks like a muscle car with legs, and Brian (Paul Walker), former federal agent. Our heroic band’s admixture of criminal and lawman is matched by the villains: the caper involves a crime lord who is also a political boss. All parties meet at money, obviously. The boss has $100 million socked away in a police station vault. Being street racers, our crew proposes to prise the vault forth from the station cabled to a couple of their vehicles, then flee through downtown Rio. But first they lay hands on an identical vault: a salute to the (remade) Ocean’s Eleven, where the team acquires a replica of the casino vault so as to practice their mechanics. In the event of it, eluding unencumbered pursuit while dragging an enormous steel oblong across pavement proves easier said than done. Call it Rio Friction, the very inverse of Tokyo Drift. Or call it Attack of the BRIC. Abandoning all hope of escape, Dom turns to use the vault as a weapon. Indeed, it has been functioning as such all along; the flight to safety, even before it becomes a demolition derby, has managed to obliterate considerable swaths of the world capital.

Not only is it impossible to imagine the characters thinking this was a good or even plausible idea for getting the dough, it is also impossible to imagine the screenwriters thinking this would make for a good caper. The ten-minute sequence is finally a bit dull; absurdity does have a way of turning to boredom.

But what if we have been thinking of this all wrong, and the entire movie is just a pretext for something else altogether? It may be narrative idiocy of the first water—but it is, we must admit, the single best cinematic representation of the global financial crisis yet contrived, immeasurably better than Inside Job or Capitalism: A Love Story.

A weaponized concentration of capital seems to be dragged about by supermen; it is in fact dragging them around, laying waste to the world before it, destroying houses and urban centers and bodies as it races for safety—before recognizing that there is no safety and it should just turn violently on its pursuers in a festival of destruction.

In the textbook definition, capital is generally self-valorizing value; in a crisis it is inverted, and becomes self-annihilating value. The supermoney that seemed to run the world is revealed as “fictitious capital,” unrealized and finally unrealizable, but still in its auto-destruction capable of laying low the world around it. Which explains what would otherwise be the most intolerable plot device. In the end, it turns out that Dom and Brian have been hauling the fake vault through the city, while the actual box is spirited away, loot enclosed. As a scheme, it’s ludicrous. As a reading of crisis in the world system, it’s immaculate—as if Hollywood had come to an intimate knowledge of volume 3 of Capital without reading, simply by bathing in the current of world money—and should complete the contemporary genre. I am seriously considering renaming this column “The Marx and the Furious.”

Now that we no longer want for figurations of the financial crisis, we can turn to what comes next, if anything, and how one imagines the vectors and contexts of an adequate response. In this arena apocalyptic pictures continue to hold us captive. The signal version this season is Contagion—arriving as an updating of the 1970s disaster flick, and bearing with it some backdated ideas indeed.

To Read the Entire Essay

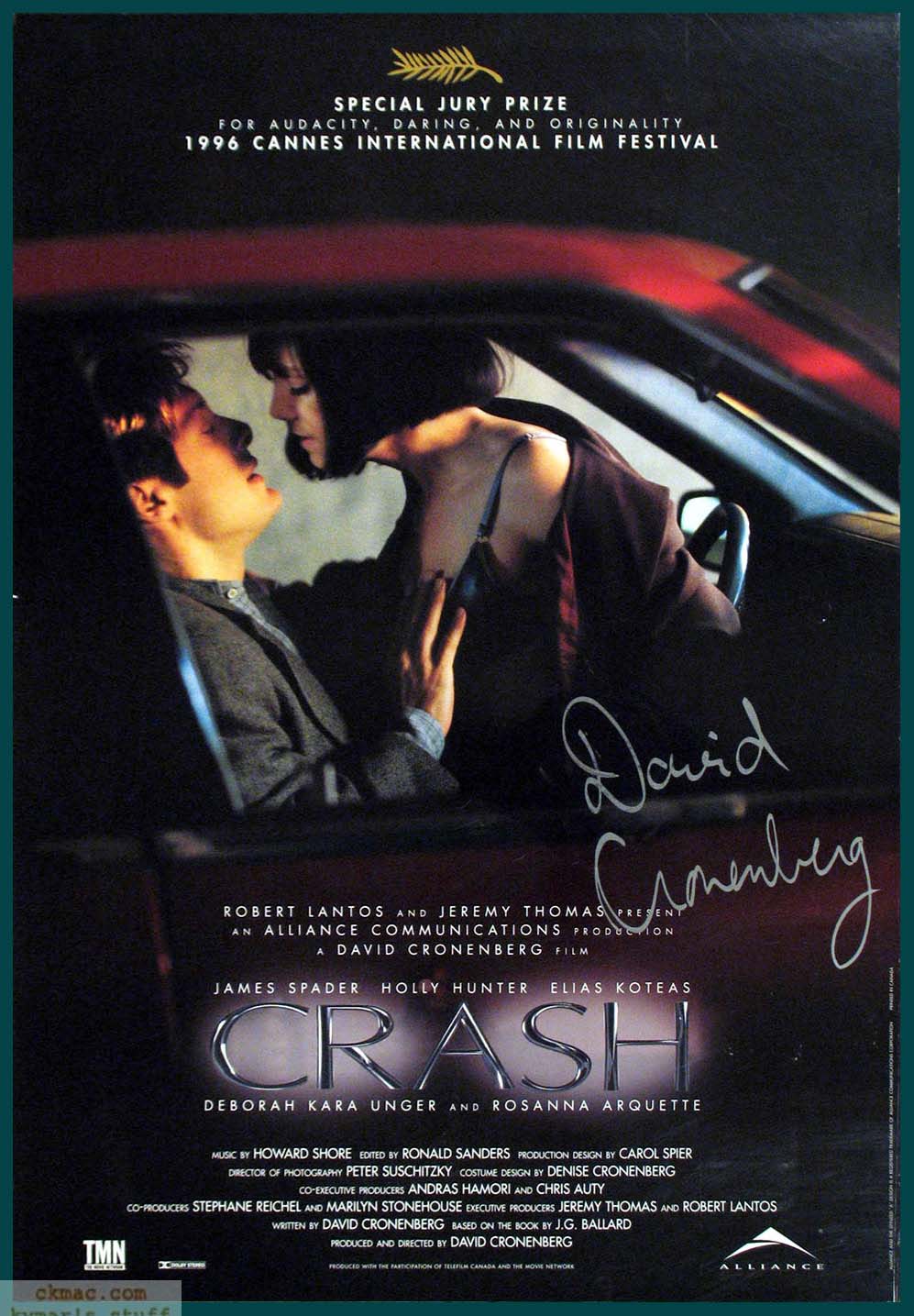

by Joshua Clover

Film Quarterly

...

But Toyota-ization too reached its limits. “Tokyo drift” describes a style of street racing where the cars are made to slide almost frictionlessly through corners, with the low impact grace of a tap dancer in a sandbox. It might just as well be a rubric for the Japanese economy of the ongoing “lost decade”—having avoided a massive economic crash, it is still unable to get back on track or restore profitability, and drifts endlessly through the long turn of late capitalism.

A consultation with reference materials suggests that Tokyo Drift was meant to be out of series and out of time; Fast Five, a less nimble film, takes place earlier. Looks like the present. So Han, a ghost of the Lost Decade, walks into a garage in the emerging economy of Brazil to take his place in the team assembled by Dom (Vin Diesel), who looks like a muscle car with legs, and Brian (Paul Walker), former federal agent. Our heroic band’s admixture of criminal and lawman is matched by the villains: the caper involves a crime lord who is also a political boss. All parties meet at money, obviously. The boss has $100 million socked away in a police station vault. Being street racers, our crew proposes to prise the vault forth from the station cabled to a couple of their vehicles, then flee through downtown Rio. But first they lay hands on an identical vault: a salute to the (remade) Ocean’s Eleven, where the team acquires a replica of the casino vault so as to practice their mechanics. In the event of it, eluding unencumbered pursuit while dragging an enormous steel oblong across pavement proves easier said than done. Call it Rio Friction, the very inverse of Tokyo Drift. Or call it Attack of the BRIC. Abandoning all hope of escape, Dom turns to use the vault as a weapon. Indeed, it has been functioning as such all along; the flight to safety, even before it becomes a demolition derby, has managed to obliterate considerable swaths of the world capital.

Not only is it impossible to imagine the characters thinking this was a good or even plausible idea for getting the dough, it is also impossible to imagine the screenwriters thinking this would make for a good caper. The ten-minute sequence is finally a bit dull; absurdity does have a way of turning to boredom.

But what if we have been thinking of this all wrong, and the entire movie is just a pretext for something else altogether? It may be narrative idiocy of the first water—but it is, we must admit, the single best cinematic representation of the global financial crisis yet contrived, immeasurably better than Inside Job or Capitalism: A Love Story.

A weaponized concentration of capital seems to be dragged about by supermen; it is in fact dragging them around, laying waste to the world before it, destroying houses and urban centers and bodies as it races for safety—before recognizing that there is no safety and it should just turn violently on its pursuers in a festival of destruction.

In the textbook definition, capital is generally self-valorizing value; in a crisis it is inverted, and becomes self-annihilating value. The supermoney that seemed to run the world is revealed as “fictitious capital,” unrealized and finally unrealizable, but still in its auto-destruction capable of laying low the world around it. Which explains what would otherwise be the most intolerable plot device. In the end, it turns out that Dom and Brian have been hauling the fake vault through the city, while the actual box is spirited away, loot enclosed. As a scheme, it’s ludicrous. As a reading of crisis in the world system, it’s immaculate—as if Hollywood had come to an intimate knowledge of volume 3 of Capital without reading, simply by bathing in the current of world money—and should complete the contemporary genre. I am seriously considering renaming this column “The Marx and the Furious.”

Now that we no longer want for figurations of the financial crisis, we can turn to what comes next, if anything, and how one imagines the vectors and contexts of an adequate response. In this arena apocalyptic pictures continue to hold us captive. The signal version this season is Contagion—arriving as an updating of the 1970s disaster flick, and bearing with it some backdated ideas indeed.

To Read the Entire Essay

Sunday, May 27, 2012

Bruce Schneier, Robert Jensen, Rob Hawkins and David Graeber: The Psychology of Transition (Undoing Millennia of Social Control)

#597 - The Psychology of Transition (Undoing Millennia of Social Control)

Unwelcome Guests

We start the show this week with a short interview of Bruce Schneier on Social Change and Defectors. He assesses the imminent threats to the internet as being layers 8 & 9 - i.e. overregulation and control by corporations and governments keen to prevent innovative use of information technology.

Next we hear Robert Jensen who starts by speaks on the entrenched mindset of hierarchy - focusing particularly on the naturalized violence against women by men, but looking at others such as racism.

Next we hear a 2009 interview by Frank of the Agroinnovations Podcast. Rob Hopkins speaks on the origins of the transition movement and shares some potential pitfalls, and his thoughts on a quote from Charles Eisenstein's 'Ascent of Humanity'. As well as discussing suburban permaculture, he discusses the practical application of the transition model as a grassroots community organizing strategy and its potential for construction of parallel systems to take over from the existing centralised power structures.

We conclude by finishing chapter 7 and starting on chapter 8 of David Graeber's Debt, The First 5000 Years.

To Listen to the Episodes

Unwelcome Guests

We start the show this week with a short interview of Bruce Schneier on Social Change and Defectors. He assesses the imminent threats to the internet as being layers 8 & 9 - i.e. overregulation and control by corporations and governments keen to prevent innovative use of information technology.

Next we hear Robert Jensen who starts by speaks on the entrenched mindset of hierarchy - focusing particularly on the naturalized violence against women by men, but looking at others such as racism.

Next we hear a 2009 interview by Frank of the Agroinnovations Podcast. Rob Hopkins speaks on the origins of the transition movement and shares some potential pitfalls, and his thoughts on a quote from Charles Eisenstein's 'Ascent of Humanity'. As well as discussing suburban permaculture, he discusses the practical application of the transition model as a grassroots community organizing strategy and its potential for construction of parallel systems to take over from the existing centralised power structures.

We conclude by finishing chapter 7 and starting on chapter 8 of David Graeber's Debt, The First 5000 Years.

To Listen to the Episodes

Michael Parenti: The Costs of Empire at Home and Abroad; Michel Chussodovsky: The International Monetary Fund (IMF)

#3 - The Costs of Empire and the IMF

Unwelcome Guests

Number 2 of our 17 part lecture series with Michael Parenti. His talk this week "The Costs of Empire at Home and Abroad". In the second hour, Economist Michel Chussodovsky.

To Listen to the Episode

Unwelcome Guests

Number 2 of our 17 part lecture series with Michael Parenti. His talk this week "The Costs of Empire at Home and Abroad". In the second hour, Economist Michel Chussodovsky.

To Listen to the Episode

Maggie Sauter: The Visual Life of Occupy Wall Street

The Visual Life of Occupy Wall Street

by Maggie Sauter

MIT Comparative Media Studies

Many visual tropes have accompanied Occupy Wall Street's rise to public prominence. In the beginning, there was the ethereal image of a ballerina poised delicately on the back of the Wall Street bull which graced the original posters and calls-for-action. There were photos of Zuccotti Park crammed with tents and blue tarps. The iconic "I am the 99%" stance, a photo of a single person, holding a handwritten sign dense with text, became a form in and of itself, attracting spinoffs, parodies, and rebuttals.

Two images, in particular, have become highly associated with the Occupy movement in the public eye: the image of Officer Pike pepper spraying students at UC Davis, popularized by the Pepper-Spray Cop remix meme; and the Guy Fawkes mask, first popularized by Anonymous. Each of these images speaks to different aspects of the Occupy movement, its origins, and its challenges, as well as hinting to where the movement will go in the future.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by Maggie Sauter

MIT Comparative Media Studies

Many visual tropes have accompanied Occupy Wall Street's rise to public prominence. In the beginning, there was the ethereal image of a ballerina poised delicately on the back of the Wall Street bull which graced the original posters and calls-for-action. There were photos of Zuccotti Park crammed with tents and blue tarps. The iconic "I am the 99%" stance, a photo of a single person, holding a handwritten sign dense with text, became a form in and of itself, attracting spinoffs, parodies, and rebuttals.

Two images, in particular, have become highly associated with the Occupy movement in the public eye: the image of Officer Pike pepper spraying students at UC Davis, popularized by the Pepper-Spray Cop remix meme; and the Guy Fawkes mask, first popularized by Anonymous. Each of these images speaks to different aspects of the Occupy movement, its origins, and its challenges, as well as hinting to where the movement will go in the future.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Saturday, May 26, 2012

Common Sense with Dan Carlin: #214 - The Bitter Harvest of Fear

Show 214 - The Bitter Harvest of Fear

Common Sense with Dan Carlin

What happens to "The Land of the Free" when it is no longer "The Home of the Brave"? You get the evisceration of constitutional protections in the name of fighting terrorism. Dan wonders why everyone is surprised.

Notes:

1. ”Detaining US citizens: How did we get here?” by D. Parvas for Al Jazeera News, December 15, 2011.

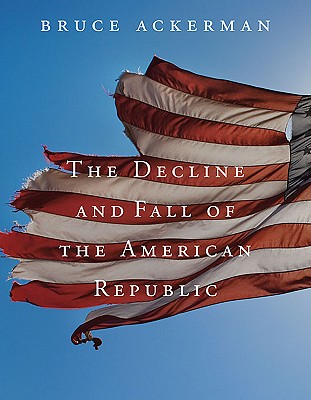

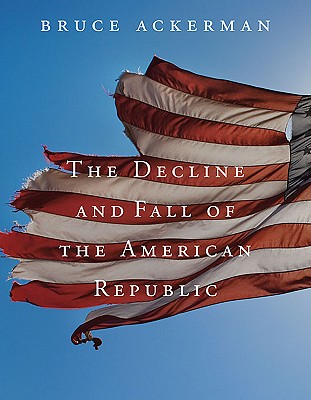

2.

To Listen to the Episode

Common Sense with Dan Carlin

What happens to "The Land of the Free" when it is no longer "The Home of the Brave"? You get the evisceration of constitutional protections in the name of fighting terrorism. Dan wonders why everyone is surprised.

Notes:

1. ”Detaining US citizens: How did we get here?” by D. Parvas for Al Jazeera News, December 15, 2011.

2.

To Listen to the Episode

Kentucky Rising (Frankfort: June 1, 2012)

Dear Friends and Allies:

I write to invite you to join fellow Kentuckians at the Capitol in Frankfort this June 1 to demand the end of corporate interference in (what should be) OUR politics, especially the overwhelming influence of the coal industry. The time to demand a participatory society for all Kentuckians is NOW!

A broad-based group of citizens is organizing a mass convergence we are calling Kentucky Rising: Occupy the Capitol. By drawing upon the energy of the Kentucky Rising sit-in of February 2011 and the momentum of the nationwide Occupy movement, we intend to create a critical mass of citizens to form a People's Assembly to give voice to concerns about injustice and to work together to find creative and positive solutions to the problems we face. We will respectfully occupy public space and the occupation will also serve as a base for teach-ins, sit-ins, and other non-violent direct actions.

We wish to encourage Kentuckians of all political inclinations to attend. While we may not all agree with each other on some things, most people can agree that corporate domination of Kentucky politics has got to go. This event will be a space for Kentuckians of all backgrounds to come together to talk with each other and find common ground. However, oppressive behavior of any sort will not be tolerated, and there will be a process for dealing with it when it arises.

As a citizen activist or organizer, you are in a crucial position to assist the event organizers in mobilizing a large and diverse group of Kentuckians on June 1 and the following days of the occupation. Will you reach out to inform and invite people in your networks to rise up, united by our love for the land and people of Kentucky?

Over the next month, please make calls and send out emails letting people know and direct them to the event website Ketucky Rising for information and updates. They can also visit the the facebook event page: here

Finally, if you would like to be more involved in organizing this event, please send your contact info, skills, and capacity to help via this web form. We believe that we are all leaders, so the organizing will be decentralized and horizontal, rather than top-down. If you know someone who would like to help organize or reach out, please forward them this email.

More than anything, we want this convergence to be a fun and family-friendly experience as well as a learning opportunity. The problems we face are dire, but if we face them together in a spirit of love and comradeship, we can create the Kentucky we want to pass on to future generations.

In Solidarity,

The Organizers of Kentucky Rising

Anna Kruzynski and Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois: Maple Spring -- Nearly 1,000 Arrested as Mass Quebec Student Strike Passes 100th Day

Maple Spring: Nearly 1,000 Arrested as Mass Quebec Student Strike Passes 100th Day

Democracy Now

More than 400,000 filled the streets of Montreal this week as a protest over a 75 percent increase in tuition has grown into a full-blown political crisis. After three months of sustained protests and class boycotts that have come to be known around the world as the "Maple Spring," the dispute exploded when the Quebec government passed an emergency law known as Bill 78, which suspends the current academic term, requires demonstrators to inform police of any protest route involving 50 or more people, and threatens student associations with fines of up to $125,000 if they disobey. The strike has received growing international attention as the standoff grows, striking a chord with young people across the globe amid growing discontent over austerity measures, bleak economies and crushing student debt. We’re joined by Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, spokesperson for CLASSE, the main coalition of student unions involved in the student strikes in Quebec, and Anna Kruzynski, assistant professor at the School of Community and Public Affairs at Concordia University in Montreal. She has been involved in the student strike as a member of the group, Professors Against the Hike.

Guests:

Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, the spokesperson for CLASSE, the main coalition of student unions involved in the student strikes in Quebec, Canada.

Anna Kruzynski, assistant professor at the School of Community and Public Affairs, Concordia University in Montreal. She’s been involved in the student strike as a member of Professors Against the Hike.

To Watch the Episode

Democracy Now

More than 400,000 filled the streets of Montreal this week as a protest over a 75 percent increase in tuition has grown into a full-blown political crisis. After three months of sustained protests and class boycotts that have come to be known around the world as the "Maple Spring," the dispute exploded when the Quebec government passed an emergency law known as Bill 78, which suspends the current academic term, requires demonstrators to inform police of any protest route involving 50 or more people, and threatens student associations with fines of up to $125,000 if they disobey. The strike has received growing international attention as the standoff grows, striking a chord with young people across the globe amid growing discontent over austerity measures, bleak economies and crushing student debt. We’re joined by Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, spokesperson for CLASSE, the main coalition of student unions involved in the student strikes in Quebec, and Anna Kruzynski, assistant professor at the School of Community and Public Affairs at Concordia University in Montreal. She has been involved in the student strike as a member of the group, Professors Against the Hike.

Guests:

Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, the spokesperson for CLASSE, the main coalition of student unions involved in the student strikes in Quebec, Canada.

Anna Kruzynski, assistant professor at the School of Community and Public Affairs, Concordia University in Montreal. She’s been involved in the student strike as a member of Professors Against the Hike.

To Watch the Episode

Friday, May 25, 2012

Sharon Kinsella: Men Imagining a Girl Revolution

"Men Imagining a Girl Revolution"

by Sharon Kinsella

CMS Colloquium (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

Foreign Languages and Literatures visiting professor Sharon Kinsella examines the media constructions of a teenage female revolt in contemporary Japan drawing from her current book project Girls as Energy: Fantasies of Social Rejuvenation.

To Listen to the Presentation

by Sharon Kinsella

CMS Colloquium (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

Foreign Languages and Literatures visiting professor Sharon Kinsella examines the media constructions of a teenage female revolt in contemporary Japan drawing from her current book project Girls as Energy: Fantasies of Social Rejuvenation.

To Listen to the Presentation

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

Matthew J. Iannucci: Postmodern Antihero -- Capitalism and Heroism in Taxi Driver

Postmodern Antihero: Capitalism and Heroism in Taxi Driver

by Matthew J. Iannucci

Bright Lights Film Journal

Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver is a gritty, disturbing, nightmarish modern film classic that examines alienation in urban society. From a postmodernist's perspective, it combines the elements of noir, the Western, horror, and urban melodrama as it explores the psychological madness within an obsessed, inarticulate, lonely antihero cab driver, Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro). The plotline is simple: Travis directs his frustrated anger at the street dwellers of New York and a presidential candidate, and his unhinging assault is paired with an attempt to rescue a young prostitute, Iris (Jodie Foster), from her predatory pimp. Historically, Taxi Driver appeared after a decade of war in Vietnam (1976), and after the Watergate crisis and subsequent resignation of Nixon. Five years later, when it was linked to would-be presidential assassin John Hinckley and his obsession with Jodie Foster, it became prima facie evidence for those on the political right who believed that violence in film translates into crime in real life. It is now almost impossible to separate Taxi Driver from this debate. However, Bickle's antiheroic character is more directly related to a failure of a capitalist system that pits his working-class position as a cab driver against those who have already been disenfranchised according to socioeconomic class, gender, and/or race.

As the film opens, Travis emerges from a forgotten Midwestern form of Americana that appears as obsolete as Travis himself in a big city heterogeneously composed of corporate financiers, political patrons, gun dealers, and prostitutes. In order to survive, he wants to "become a person like other people" as he puts it, but his own disenfranchisement from this nation has left him both intellectually and emotionally bankrupt from the Vietnam War. Freedom, the very nucleus of the American dream, is dependent on individual socioeconomic choices that inform and shape one's identity. But Travis's lack of a distinct identity compels him to cut and paste together what he believes is a heroic identity from an external menu of personages such as the "gunslinger" and the Indian. In actuality, what he does is stitch together a postmodern antiheroic identity that is nostalgic and pop culture-oriented, evidenced by the Mohawk haircut that he sports in the penultimate sequences — because he possesses no internal self.

Taxi Driver implies that identity is not genuine but always synergistic, a kind of potpourri of idolatry and maxims drawn from popular culture, especially from violent movies and television news. In this vein, Robert Ray views Taxi Driver as a postmodern "corrected" Right film, the type of film generally aimed at a naïve audience. Ray explains that a "Right" film presents a traditional conservative philosophy that promotes the application of Western-style, individual solutions to complex contemporary problems. He writes, "Taxi Driver's basic story followed the right wing's loyalty to the classic Western formula: a reluctant individual, confronted by evil, acts on his own to rid society of spoilers. As played by Robert De Niro, Taxi Driver's protagonist had obvious connections with Western heroes…even his name, Travis, linked him to the defender of the Alamo."1 Ray's notion that the film is a "correction" of the right-wing concept of justice is accurate because of its odd plot twist at the conclusion. Normally, such a story would identify Travis's complicity with these criminals and thereby relegate him to some form of institutional punishment. But the film's underlying theme reveals how absurd the Western idealistic depiction of heroism is because the news media in the film not only ignores his actions but also glorifies a psychopathic killer as a noble warrior.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by Matthew J. Iannucci

Bright Lights Film Journal

Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver is a gritty, disturbing, nightmarish modern film classic that examines alienation in urban society. From a postmodernist's perspective, it combines the elements of noir, the Western, horror, and urban melodrama as it explores the psychological madness within an obsessed, inarticulate, lonely antihero cab driver, Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro). The plotline is simple: Travis directs his frustrated anger at the street dwellers of New York and a presidential candidate, and his unhinging assault is paired with an attempt to rescue a young prostitute, Iris (Jodie Foster), from her predatory pimp. Historically, Taxi Driver appeared after a decade of war in Vietnam (1976), and after the Watergate crisis and subsequent resignation of Nixon. Five years later, when it was linked to would-be presidential assassin John Hinckley and his obsession with Jodie Foster, it became prima facie evidence for those on the political right who believed that violence in film translates into crime in real life. It is now almost impossible to separate Taxi Driver from this debate. However, Bickle's antiheroic character is more directly related to a failure of a capitalist system that pits his working-class position as a cab driver against those who have already been disenfranchised according to socioeconomic class, gender, and/or race.

As the film opens, Travis emerges from a forgotten Midwestern form of Americana that appears as obsolete as Travis himself in a big city heterogeneously composed of corporate financiers, political patrons, gun dealers, and prostitutes. In order to survive, he wants to "become a person like other people" as he puts it, but his own disenfranchisement from this nation has left him both intellectually and emotionally bankrupt from the Vietnam War. Freedom, the very nucleus of the American dream, is dependent on individual socioeconomic choices that inform and shape one's identity. But Travis's lack of a distinct identity compels him to cut and paste together what he believes is a heroic identity from an external menu of personages such as the "gunslinger" and the Indian. In actuality, what he does is stitch together a postmodern antiheroic identity that is nostalgic and pop culture-oriented, evidenced by the Mohawk haircut that he sports in the penultimate sequences — because he possesses no internal self.

Taxi Driver implies that identity is not genuine but always synergistic, a kind of potpourri of idolatry and maxims drawn from popular culture, especially from violent movies and television news. In this vein, Robert Ray views Taxi Driver as a postmodern "corrected" Right film, the type of film generally aimed at a naïve audience. Ray explains that a "Right" film presents a traditional conservative philosophy that promotes the application of Western-style, individual solutions to complex contemporary problems. He writes, "Taxi Driver's basic story followed the right wing's loyalty to the classic Western formula: a reluctant individual, confronted by evil, acts on his own to rid society of spoilers. As played by Robert De Niro, Taxi Driver's protagonist had obvious connections with Western heroes…even his name, Travis, linked him to the defender of the Alamo."1 Ray's notion that the film is a "correction" of the right-wing concept of justice is accurate because of its odd plot twist at the conclusion. Normally, such a story would identify Travis's complicity with these criminals and thereby relegate him to some form of institutional punishment. But the film's underlying theme reveals how absurd the Western idealistic depiction of heroism is because the news media in the film not only ignores his actions but also glorifies a psychopathic killer as a noble warrior.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Michael D. Yates: The Great Inequality

The Great Inequality

by Michael D. Yates

Monthly Review

...

Schutz’s approach here is ingenious, and it takes us directly to a consideration of class not just as a condition—as in, you and I are in different social classes—but as a dynamic relationship in which one class exercises power over another so that society is structured in such a way that there can be no escape from persistent inequalities unless the power (class) relationship is confronted directly and abolished. As we make our choices, we also collectively make “social choices,” that is we structure the very society that faces us with constraints when we choose. However, to say this is to suggest that we are not at all equal in terms of how society itself is constructed. At the level of society, power is critically important. Here is how Schutz defines power: “If person A can get person B to do something in A’s interest by taking advantage of some situation or set of circumstances to which B, were he or she free to choose with full knowledge from among all possible alternatives, would not give full consent, then A has power over B” (66).

While this is a general definition, it is still possible immediately to say some particular things about power. First, power allows a person unilaterally to change another’s constraints, and it can, when exercised long enough, change the habits of subordinates so that the latter act automatically in the interests of their masters. Second, those with personal power will inevitably also have social power, and this will allow them to make the rules that all must obey, and these will benefit the powerful. These rules, in turn, may come to seem normal, which lowers any costs the powerful would have to incur to maintain their power. Third, wherever there is power, there can be no democracy, since if there were, such power would be abolished by majority rule.

After defining power, Schutz examines it in a capitalist context. The most important kind of power is that which employers exert at the workplace. The power advantage capitalists have vis-à-vis their employees is as obvious as it is neglected by mainstream economists. Workers do not have the wealth to withstand periods without employment, and while they might quit a particular job, they cannot quit all jobs. In addition, the ownership of businesses gives capitalists the legal right to structure their workplaces (through detailed division of labor, mechanization, close monitoring to ensure maximum intensity, and so forth) so that the amount of labor used is always a good deal less than the supply of workers. This pool of surplus labor, Marx’s “reserve army,” serves to keep the employed in line, from making excessive wage and hour demands on the bosses. Employers also create artificial job hierarchies to split workers and keep them from seeing their common interests. In larger firms, seemingly impersonal bureaucracies make rules that come to be accepted as inevitable and even fair. All of these things allow employers to extract a surplus of work from their hired hands, a surplus that the employers get to keep. Power always involves a “taking” by the powerful from those without it. What is taken is the fruits of the exercise of their labor time. The control of the labor power of others over a definite period of time, in other words, is the principal basis of economic profit and power under capitalism.

Of course, a “pure” model of power in capitalism, one in which the capitalists merely exploit workers and the analysis stops there, is too simple, even if it remains the essential starting point, and Schutz devotes chapters to other classes, such as managers and professionals, to the hierarchy of businesses (with the largest monopoly capitals at the top), to political power, and to the power represented by complex social networks and cultural institutions such as colleges and universities and media. Each of these other power hierarchies has a certain degree of independence from the basic economic hierarchy, but each is, in the end, connected to it. Together, they serve inevitably to reinforce it; they make it more impregnable to change by, in large part, making it appear normal, the consequence of human nature, and creative of the best world possible. All of these other power structures make our economic system extraordinarily complex and difficult to penetrate, but they do not negate the essential importance of the capital-labor power inequality. They come into being because of it, and they make it stronger. We cannot understand any of them if we do not grasp it.

Once Schutz has laid out his theoretical position on inequality, he addresses the question of why it has risen so dramatically in the United States. He critiques several mainstream hypotheses, the most important of which is that the information technology revolution has raised the skill requirements (education and training costs) at the upper end of the wage hierarchy, while these costs at the lower end have either not risen or fallen. Since, according to neoclassical theory, wages equal the costs of entry into an occupation, this implies that wages at the top are rising disproportionately to those at the bottom. Schutz points out that wage equality began to rise at least a decade before the IT revolution took off. Also, education and training have become more equally distributed, and this should have been reflected in more equality. And if we consider a particular skill group, say those with college degrees in a certain field, inequality has risen within such groups. Schutz might have noted as well that the de-skilling practices associated with Frederick Taylor are deeply ingrained in what all managements do, so that any argument concerning widespread and long-lasting increases in skill requirements is implausible.

To Read the Entire Essay

by Michael D. Yates

Monthly Review

...

Schutz’s approach here is ingenious, and it takes us directly to a consideration of class not just as a condition—as in, you and I are in different social classes—but as a dynamic relationship in which one class exercises power over another so that society is structured in such a way that there can be no escape from persistent inequalities unless the power (class) relationship is confronted directly and abolished. As we make our choices, we also collectively make “social choices,” that is we structure the very society that faces us with constraints when we choose. However, to say this is to suggest that we are not at all equal in terms of how society itself is constructed. At the level of society, power is critically important. Here is how Schutz defines power: “If person A can get person B to do something in A’s interest by taking advantage of some situation or set of circumstances to which B, were he or she free to choose with full knowledge from among all possible alternatives, would not give full consent, then A has power over B” (66).

While this is a general definition, it is still possible immediately to say some particular things about power. First, power allows a person unilaterally to change another’s constraints, and it can, when exercised long enough, change the habits of subordinates so that the latter act automatically in the interests of their masters. Second, those with personal power will inevitably also have social power, and this will allow them to make the rules that all must obey, and these will benefit the powerful. These rules, in turn, may come to seem normal, which lowers any costs the powerful would have to incur to maintain their power. Third, wherever there is power, there can be no democracy, since if there were, such power would be abolished by majority rule.

After defining power, Schutz examines it in a capitalist context. The most important kind of power is that which employers exert at the workplace. The power advantage capitalists have vis-à-vis their employees is as obvious as it is neglected by mainstream economists. Workers do not have the wealth to withstand periods without employment, and while they might quit a particular job, they cannot quit all jobs. In addition, the ownership of businesses gives capitalists the legal right to structure their workplaces (through detailed division of labor, mechanization, close monitoring to ensure maximum intensity, and so forth) so that the amount of labor used is always a good deal less than the supply of workers. This pool of surplus labor, Marx’s “reserve army,” serves to keep the employed in line, from making excessive wage and hour demands on the bosses. Employers also create artificial job hierarchies to split workers and keep them from seeing their common interests. In larger firms, seemingly impersonal bureaucracies make rules that come to be accepted as inevitable and even fair. All of these things allow employers to extract a surplus of work from their hired hands, a surplus that the employers get to keep. Power always involves a “taking” by the powerful from those without it. What is taken is the fruits of the exercise of their labor time. The control of the labor power of others over a definite period of time, in other words, is the principal basis of economic profit and power under capitalism.

Of course, a “pure” model of power in capitalism, one in which the capitalists merely exploit workers and the analysis stops there, is too simple, even if it remains the essential starting point, and Schutz devotes chapters to other classes, such as managers and professionals, to the hierarchy of businesses (with the largest monopoly capitals at the top), to political power, and to the power represented by complex social networks and cultural institutions such as colleges and universities and media. Each of these other power hierarchies has a certain degree of independence from the basic economic hierarchy, but each is, in the end, connected to it. Together, they serve inevitably to reinforce it; they make it more impregnable to change by, in large part, making it appear normal, the consequence of human nature, and creative of the best world possible. All of these other power structures make our economic system extraordinarily complex and difficult to penetrate, but they do not negate the essential importance of the capital-labor power inequality. They come into being because of it, and they make it stronger. We cannot understand any of them if we do not grasp it.

Once Schutz has laid out his theoretical position on inequality, he addresses the question of why it has risen so dramatically in the United States. He critiques several mainstream hypotheses, the most important of which is that the information technology revolution has raised the skill requirements (education and training costs) at the upper end of the wage hierarchy, while these costs at the lower end have either not risen or fallen. Since, according to neoclassical theory, wages equal the costs of entry into an occupation, this implies that wages at the top are rising disproportionately to those at the bottom. Schutz points out that wage equality began to rise at least a decade before the IT revolution took off. Also, education and training have become more equally distributed, and this should have been reflected in more equality. And if we consider a particular skill group, say those with college degrees in a certain field, inequality has risen within such groups. Schutz might have noted as well that the de-skilling practices associated with Frederick Taylor are deeply ingrained in what all managements do, so that any argument concerning widespread and long-lasting increases in skill requirements is implausible.

To Read the Entire Essay

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

Rick Perlstein: Chicago History Repeats Itself As Cops and Protesters Clash

Chicago History Repeats Itself As Cops and Protesters Clash

by Rick Perlstein

Rolling Stone

In 1972, writing in Rolling Stone about a looming confrontation between protesters and police in the streets in front of the Republican National Convention in Miami, Hunter S. Thompson described the moment he slipped off his watch. "The first thing to go in a street fight is always your watch, and once you've lost a few, you develop a certain instinct that lets you know it's time to get the thing off your wrist and into a safe pocket." Times have changed: Few people wear watches any more. So when the first objects starting flying in Chicago yesterday night on the corner of Cermak and Michigan, I buttoned my cell phone into my cargo pants pocket instead.

I'd begun marching, four hours earlier, from the bandshell behind the Art Institute of Chicago to a temporary protest zone with 2,000 people (by city estimates) protesting NATO’s role in the Afghanistan war. Our destination was a half mile east of the NATO summit taking place at the south-of-downtown McCormick Place Convention Center; it had been an awkward traipse. I was following legal observers from the National Lawyers Guild; they were watching the police, who were everywhere: thousands were deployed for the summit, plus ringers from forty other agencies from as far away as North Carolina. At least a few hundred were in my field of vision at all times. Volunteers surrounded the parade column with yellow cord; just outside that perimeter hundreds of officers kept stride, all of us starting, stopping, slowing up at a pace dictated by the police wagons inching along ahead.

Up ahead, from sidewalk to sidewalk, marched another row of cops, walking backward, sometimes joining hands red-rover style. Flying squadrons of riot police in those fearsome security-visored blue helmets, chest-protectors that make them look like black turtles, and massively bulging shiny shin guards sometimes appeared, then disappeared down abandoned side streets. Then, at the march's culmination at a makeshift stage 800 yards and innumerable eight-foot-tall steel security barriers west of where 65 world leaders were gathering to talk, largely about the course of the war in Afghanistan, they were suddenly among us, en masse: black turtles, row upon row, arrayed on the elevated median strips that afforded them the high ground for whatever battle might ensue.

This was Chicago in May of 2012, where all week citizens have been cordially invited by authorities to savor what it would feel like to live in a police state – 7.5 miles of street closings; several "maritime security zones"; the thwukthwukthwuk of helicopters and the continuous scream of jet fighters overhead; those infamous "Long Range Acoustic Devices" that make it too painful to stand, poised at the ready; and, in one particularly surreal touch in my tranquil Hyde Park neighborhood, a misplaced suitcase that shut down the 57th Street train station as well access to the two adjacent nerdy used bookstores, a full forty blocks from the NATO zone. (An email to every University of Chicago student, staffer, and faculty member: "Police activity 57th Street at Metra. Avoid area. Additional information to follow." Thirty-nine minutes later: "All clear 57th Street and Metra. Will resume normal operations.")

Just as intended, the city thrummed with fear, uncertainty, and doubt, the most effective tool the powerful possess to keep the rest of us in line; so pervasive was the dread that people working downtown wore jeans on Thursday (no one showed up to work on Friday), lest they be randomly attacked by "self-described anarchists" – in the news media's odd formulation – mistaking them for members of "the 1%."

That night, it all came to a head with the warrantless violent police raid of an apartment in the gentrifying neighborhood of Pilsen, followed by the "disappearing" – no other term for it – of three anarchists, Jared Chase, 27, Brian Church, 22, and Brent Betterly, 24, for over twenty-four hours. They resurfaced Saturday in a Cook County courtroom, where they were charged with "conspiring to commit domestic terrorism during the NATO summit," including "plotting to attack President Obama's Chicago campaign headquarters, the Chicago mayor's home and police stations." What the suspects said was home-brew equipment the city insisted was the makings of Molotov cocktails. Bail was set at $1.5 million.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by Rick Perlstein

Rolling Stone

In 1972, writing in Rolling Stone about a looming confrontation between protesters and police in the streets in front of the Republican National Convention in Miami, Hunter S. Thompson described the moment he slipped off his watch. "The first thing to go in a street fight is always your watch, and once you've lost a few, you develop a certain instinct that lets you know it's time to get the thing off your wrist and into a safe pocket." Times have changed: Few people wear watches any more. So when the first objects starting flying in Chicago yesterday night on the corner of Cermak and Michigan, I buttoned my cell phone into my cargo pants pocket instead.

I'd begun marching, four hours earlier, from the bandshell behind the Art Institute of Chicago to a temporary protest zone with 2,000 people (by city estimates) protesting NATO’s role in the Afghanistan war. Our destination was a half mile east of the NATO summit taking place at the south-of-downtown McCormick Place Convention Center; it had been an awkward traipse. I was following legal observers from the National Lawyers Guild; they were watching the police, who were everywhere: thousands were deployed for the summit, plus ringers from forty other agencies from as far away as North Carolina. At least a few hundred were in my field of vision at all times. Volunteers surrounded the parade column with yellow cord; just outside that perimeter hundreds of officers kept stride, all of us starting, stopping, slowing up at a pace dictated by the police wagons inching along ahead.

Up ahead, from sidewalk to sidewalk, marched another row of cops, walking backward, sometimes joining hands red-rover style. Flying squadrons of riot police in those fearsome security-visored blue helmets, chest-protectors that make them look like black turtles, and massively bulging shiny shin guards sometimes appeared, then disappeared down abandoned side streets. Then, at the march's culmination at a makeshift stage 800 yards and innumerable eight-foot-tall steel security barriers west of where 65 world leaders were gathering to talk, largely about the course of the war in Afghanistan, they were suddenly among us, en masse: black turtles, row upon row, arrayed on the elevated median strips that afforded them the high ground for whatever battle might ensue.

This was Chicago in May of 2012, where all week citizens have been cordially invited by authorities to savor what it would feel like to live in a police state – 7.5 miles of street closings; several "maritime security zones"; the thwukthwukthwuk of helicopters and the continuous scream of jet fighters overhead; those infamous "Long Range Acoustic Devices" that make it too painful to stand, poised at the ready; and, in one particularly surreal touch in my tranquil Hyde Park neighborhood, a misplaced suitcase that shut down the 57th Street train station as well access to the two adjacent nerdy used bookstores, a full forty blocks from the NATO zone. (An email to every University of Chicago student, staffer, and faculty member: "Police activity 57th Street at Metra. Avoid area. Additional information to follow." Thirty-nine minutes later: "All clear 57th Street and Metra. Will resume normal operations.")

Just as intended, the city thrummed with fear, uncertainty, and doubt, the most effective tool the powerful possess to keep the rest of us in line; so pervasive was the dread that people working downtown wore jeans on Thursday (no one showed up to work on Friday), lest they be randomly attacked by "self-described anarchists" – in the news media's odd formulation – mistaking them for members of "the 1%."

That night, it all came to a head with the warrantless violent police raid of an apartment in the gentrifying neighborhood of Pilsen, followed by the "disappearing" – no other term for it – of three anarchists, Jared Chase, 27, Brian Church, 22, and Brent Betterly, 24, for over twenty-four hours. They resurfaced Saturday in a Cook County courtroom, where they were charged with "conspiring to commit domestic terrorism during the NATO summit," including "plotting to attack President Obama's Chicago campaign headquarters, the Chicago mayor's home and police stations." What the suspects said was home-brew equipment the city insisted was the makings of Molotov cocktails. Bail was set at $1.5 million.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Monday, May 21, 2012

Jake Olzen: Police Entrapment of Nonviolent Movements

Police Entrapment of Nonviolent Movements

by JAKE OLZEN

Counterpunch

The old trope of the bomb-throwing anarchist is back in the news, with a round-up in Ohio on May 1 and the three would-be NATO protesters arrested on Wednesday who are now charged with conspiracy to commit terrorism. While the impression that appears in the media is one of remnants of the Occupy movement verging toward violence, the driving forces behind these plots are the very agencies claiming to have foiled them.

The five activists arrested in Cleveland, Ohio, are facing multiple charges for conspiring and attempting to destroy the Brecksville-Northfield High Level Bridge on May Day to protest corporate rule. According to the FBI press statement released shortly after the May 1 arrests, FBI Special Agent in Charge Stephen D. Anthony said “the individuals charged in this plot were intent on using violence to express their ideological views.” But that is only one side of the story.

The mainstream media and blog reports, both nationally and in Cleveland, have emphasized that the young activists were part of Occupy Cleveland and self-identified anarchists (here, here, and here). The men — Douglas L. Wright, 26, of Indianapolis; Brandon L. Baxter, 20, of nearby Lakewood; Connor C. Stevens, 20, of suburban Berea; and Joshua S. Stafford, 23, and Anthony Hayne, 35, both of Cleveland — were arrested and remain in jail after they attempted to detonate a false bomb that they had set, in conjunction with the FBI.

It’s an old script: Violence-prone anarchists devise a nefarious plan and, just before they can carry it out, law enforcement swoops in to save the day, catching them red-handed. But there’s another script being acted out here too, one much more sinister, complex, and morally and legally dubious: Agents of the state infiltrate an activist group and, through techniques of psychological manipulation, lead its most vulnerable members into a violent plan — for which explosives, detonators, contacts and case mysteriously become available — until SWAT teams and prosecutors suddenly arrive and haul the accomplices off to jail for the rest of their lives. In both cases, at the end of the story, officials congratulate each other for their bravery and bravado and the public breathes a sigh of relief as more of their civil liberties are stripped away.

I recently spoke with Richard Schulte, a veteran activist who has known the Five from groups like Food Not Bombs and is helping to organize their legal and jail support. Schulte explained that under the influence of undercover federal agents and informants, the activists — particularly the youngest, Baxter and Stevens — found themselves increasingly vulnerable and reliant on their informant. Baxter’s lawyer, a public defender named John Pyle, recently identified the informant working with the group as Shaquille Azir, a 39-year old ex-con.

“[Azir] became something of a role model, stepping in as a father figure, offering guidance on emotional and social stuff,” said Schulte. “Connor and Brandon thought he was a rad dude but getting more and more pushy.”

Collectively, according to accounts from friends and associates, statements from lawyers, and the FBI affidavit, members of the Cleveland Five have backgrounds that include mental illness, substance abuse, homelessness and social marginalization.

Brandon and Connor had been part of the full-time occupation over the winter in Cleveland’s Public Square. After having grown frustrated with what they perceived as the Occupiers’ timidity — Schulte called it “passive gradualism” — the Five were encouraged by Azir to break off from Occupy Cleveland and form their own, much smaller group, “The People’s Liberation Army.” At first it was mostly just a graffiti crew — tagging the phrase “rise up” around the city and putting up stickers, said Schulte.

Azir would give them a case of beer in the morning, according to Schulte, have them work outside on houses all day, and then give them a case of beer at night. He gave them marijuana and would wear them down by keeping them up late into the night with drinking and conversation — all the while urging them to break away from other groups, keep their arrangement secret and not to trust other activists.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by JAKE OLZEN

Counterpunch

The old trope of the bomb-throwing anarchist is back in the news, with a round-up in Ohio on May 1 and the three would-be NATO protesters arrested on Wednesday who are now charged with conspiracy to commit terrorism. While the impression that appears in the media is one of remnants of the Occupy movement verging toward violence, the driving forces behind these plots are the very agencies claiming to have foiled them.

The five activists arrested in Cleveland, Ohio, are facing multiple charges for conspiring and attempting to destroy the Brecksville-Northfield High Level Bridge on May Day to protest corporate rule. According to the FBI press statement released shortly after the May 1 arrests, FBI Special Agent in Charge Stephen D. Anthony said “the individuals charged in this plot were intent on using violence to express their ideological views.” But that is only one side of the story.

The mainstream media and blog reports, both nationally and in Cleveland, have emphasized that the young activists were part of Occupy Cleveland and self-identified anarchists (here, here, and here). The men — Douglas L. Wright, 26, of Indianapolis; Brandon L. Baxter, 20, of nearby Lakewood; Connor C. Stevens, 20, of suburban Berea; and Joshua S. Stafford, 23, and Anthony Hayne, 35, both of Cleveland — were arrested and remain in jail after they attempted to detonate a false bomb that they had set, in conjunction with the FBI.

It’s an old script: Violence-prone anarchists devise a nefarious plan and, just before they can carry it out, law enforcement swoops in to save the day, catching them red-handed. But there’s another script being acted out here too, one much more sinister, complex, and morally and legally dubious: Agents of the state infiltrate an activist group and, through techniques of psychological manipulation, lead its most vulnerable members into a violent plan — for which explosives, detonators, contacts and case mysteriously become available — until SWAT teams and prosecutors suddenly arrive and haul the accomplices off to jail for the rest of their lives. In both cases, at the end of the story, officials congratulate each other for their bravery and bravado and the public breathes a sigh of relief as more of their civil liberties are stripped away.

I recently spoke with Richard Schulte, a veteran activist who has known the Five from groups like Food Not Bombs and is helping to organize their legal and jail support. Schulte explained that under the influence of undercover federal agents and informants, the activists — particularly the youngest, Baxter and Stevens — found themselves increasingly vulnerable and reliant on their informant. Baxter’s lawyer, a public defender named John Pyle, recently identified the informant working with the group as Shaquille Azir, a 39-year old ex-con.

“[Azir] became something of a role model, stepping in as a father figure, offering guidance on emotional and social stuff,” said Schulte. “Connor and Brandon thought he was a rad dude but getting more and more pushy.”

Collectively, according to accounts from friends and associates, statements from lawyers, and the FBI affidavit, members of the Cleveland Five have backgrounds that include mental illness, substance abuse, homelessness and social marginalization.

Brandon and Connor had been part of the full-time occupation over the winter in Cleveland’s Public Square. After having grown frustrated with what they perceived as the Occupiers’ timidity — Schulte called it “passive gradualism” — the Five were encouraged by Azir to break off from Occupy Cleveland and form their own, much smaller group, “The People’s Liberation Army.” At first it was mostly just a graffiti crew — tagging the phrase “rise up” around the city and putting up stickers, said Schulte.

Azir would give them a case of beer in the morning, according to Schulte, have them work outside on houses all day, and then give them a case of beer at night. He gave them marijuana and would wear them down by keeping them up late into the night with drinking and conversation — all the while urging them to break away from other groups, keep their arrangement secret and not to trust other activists.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Trevor Link: Polisse

Polisse

by Trevor Link

Spectrum Culture

It goes without saying that the subject matter of Polisse is dispiriting and heartbreaking: a group of police officers working for the Child Protection Unit (or CPU) in Paris deal, on a daily basis, with cases involving rape, abuse, prostitution and organized crime. To compound this bleakness, the details of these cases were, in fact, drawn from real life: director and co-writer Maïwenn spent time following actual officers and constructed her film from events she witnessed or heard about during that time. This patina of ultra-realism coats the events in the film, making them reverberate beyond the screen and suggesting, for each unimaginable horror, a series of unseen but real-life analogues. Maïwenn wisely eschews the tedious offering of answers; her film is instead satisfied in tracing the outline of a vast problem, letting its shape impress an urgent tenseness upon us. Unable to intervene, Maïwenn’s camera can only observe, bringing us back once again to a fundamental question of cinema: to what extent can merely seeing the events of the world—bearing witness to them—actually matter?

Polisse is most interesting when it stays faithful to this ocular theme. As Carol J. Clover has noted in her study of horror films, the eye itself, despite being considered a source of domination (the gaze), is actually quite vulnerable and penetrable (the eyeball-impaling sequence from Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2 drives this point home quite strikingly). Filmmakers have moreover understood the camera, like the eye, to be an instrument of control and even aggression—its phallic associations reached a climax in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, which coupled masculine ineffectuality and truth’s elusiveness: together, a lack of mastery. These associations are reversed in Polisse through the character of Mélissa (played by Maïwenn herself), a photographer tasked with documenting the work of the CPU. Mélissa embodies the eye’s vulnerability, and her camera bestows upon her the power of empathy, an uncontrollable receptivity that manifests as an openness to the plight of others. Following the CPU around, she becomes shaken by the horror she sees, the documentation of which cannot console her, but her role is to look—to look only—and take in what she sees, the camera and the eye functioning in tandem.

To Read the Rest of the Review

by Trevor Link

Spectrum Culture