"My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel--it is, above all, to make you see." -- Joseph Conrad (1897)

Monday, September 30, 2013

Sunday, September 29, 2013

On the Media - Sarah Abdurrahman: My Detainment Story or: How I learned to Stop Feeling Safe in My Own Country and Hate Border Agents

My Detainment Story or: How I learned to Stop Feeling Safe in My Own Country and Hate Border Agents*

On the Media

Earlier this month, On the Media producer Sarah Abdurrahman, her family, and her friends were detained for hours by US Customs and Border Protection on their way home from Canada. Everyone being held was a US citizen, and no one received an explanation. Sarah tells the story of their detainment, and her difficulty getting any answers from one of the least transparent agencies in the country.

To Listen to the Episode

On the Media

Earlier this month, On the Media producer Sarah Abdurrahman, her family, and her friends were detained for hours by US Customs and Border Protection on their way home from Canada. Everyone being held was a US citizen, and no one received an explanation. Sarah tells the story of their detainment, and her difficulty getting any answers from one of the least transparent agencies in the country.

To Listen to the Episode

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Matt Taibbi: Looting the Pension Funds

Looting the Pension Funds: All across America, Wall Street is grabbing money meant for public workers

By Matt Taibbi

Rolling Stone

In the final months of 2011, almost two years before the city of Detroit would shock America by declaring bankruptcy in the face of what it claimed were insurmountable pension costs, the state of Rhode Island took bold action to avert what it called its own looming pension crisis. Led by its newly elected treasurer, Gina Raimondo – an ostentatiously ambitious 42-year-old Rhodes scholar and former venture capitalist – the state declared war on public pensions, ramming through an ingenious new law slashing benefits of state employees with a speed and ferocity seldom before seen by any local government.

Called the Rhode Island Retirement Security Act of 2011, her plan would later be hailed as the most comprehensive pension reform ever implemented. The rap was so convincing at first that the overwhelmed local burghers of her little petri-dish state didn't even know how to react. "She's Yale, Harvard, Oxford – she worked on Wall Street," says Paul Doughty, the current president of the Providence firefighters union. "Nobody wanted to be the first to raise his hand and admit he didn't know what the fuck she was talking about."

Soon she was being talked about as a probable candidate for Rhode Island's 2014 gubernatorial race. By 2013, Raimondo had raised more than $2 million, a staggering sum for a still-undeclared candidate in a thimble-size state. Donors from Wall Street firms like Goldman Sachs, Bain Capital and JPMorgan Chase showered her with money, with more than $247,000 coming from New York contributors alone. A shadowy organization called EngageRI, a public-advocacy group of the 501(c)4 type whose donors were shielded from public scrutiny by the infamous Citizens United decision, spent $740,000 promoting Raimondo's ideas. Within Rhode Island, there began to be whispers that Raimondo had her sights on the presidency. Even former Obama right hand and Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel pointed to Rhode Island as an example to be followed in curing pension woes.

What few people knew at the time was that Raimondo's "tool kit" wasn't just meant for local consumption. The dynamic young Rhodes scholar was allowing her state to be used as a test case for the rest of the country, at the behest of powerful out-of-state financiers with dreams of pushing pension reform down the throats of taxpayers and public workers from coast to coast. One of her key supporters was billionaire former Enron executive John Arnold – a dickishly ubiquitous young right-wing kingmaker with clear designs on becoming the next generation's Koch brothers, and who for years had been funding a nationwide campaign to slash benefits for public workers.

Nor did anyone know that part of Raimondo's strategy for saving money involved handing more than $1 billion – 14 percent of the state fund – to hedge funds, including a trio of well-known New York-based funds: Dan Loeb's Third Point Capital was given $66 million, Ken Garschina's Mason Capital got $64 million and $70 million went to Paul Singer's Elliott Management. The funds now stood collectively to be paid tens of millions in fees every single year by the already overburdened taxpayers of her ostensibly flat-broke state. Felicitously, Loeb, Garschina and Singer serve on the board of the Manhattan Institute, a prominent conservative think tank with a history of supporting benefit-slashing reforms. The institute named Raimondo its 2011 "Urban Innovator" of the year.

The state's workers, in other words, were being forced to subsidize their own political disenfranchisement, coughing up at least $200 million to members of a group that had supported anti-labor laws. Later, when Edward Siedle, a former SEC lawyer, asked Raimondo in a column for Forbes.com how much the state was paying in fees to these hedge funds, she first claimed she didn't know. Raimondo later told the Providence Journal she was contractually obliged to defer to hedge funds on the release of "proprietary" information, which immediately prompted a letter in protest from a series of freaked-out interest groups. Under pressure, the state later released some fee information, but the information was originally kept hidden, even from the workers themselves. "When I asked, I was basically hammered," says Marcia Reback, a former sixth-grade schoolteacher and retired Providence Teachers Union president who serves as the lone union rep on Rhode Island's nine-member State Investment Commission. "I couldn't get any information about the actual costs."

This is the third act in an improbable triple-fucking of ordinary people that Wall Street is seeking to pull off as a shocker epilogue to the crisis era. Five years ago this fall, an epidemic of fraud and thievery in the financial-services industry triggered the collapse of our economy. The resultant loss of tax revenue plunged states everywhere into spiraling fiscal crises, and local governments suffered huge losses in their retirement portfolios – remember, these public pension funds were some of the most frequently targeted suckers upon whom Wall Street dumped its fraud-riddled mortgage-backed securities in the pre-crash years.

Today, the same Wall Street crowd that caused the crash is not merely rolling in money again but aggressively counterattacking on the public-relations front. The battle increasingly centers around public funds like state and municipal pensions. This war isn't just about money. Crucially, in ways invisible to most Americans, it's also about blame. In state after state, politicians are following the Rhode Island playbook, using scare tactics and lavishly funded PR campaigns to cast teachers, firefighters and cops – not bankers – as the budget-devouring boogeymen responsible for the mounting fiscal problems of America's states and cities.

Not only did these middle-class workers already lose huge chunks of retirement money to huckster financiers in the crash, and not only are they now being asked to take the long-term hit for those years of greed and speculative excess, but in many cases they're also being forced to sit by and watch helplessly as Gordon Gekko wanna-be's like Loeb or scorched-earth takeover artists like Bain Capital are put in charge of their retirement savings.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

By Matt Taibbi

Rolling Stone

In the final months of 2011, almost two years before the city of Detroit would shock America by declaring bankruptcy in the face of what it claimed were insurmountable pension costs, the state of Rhode Island took bold action to avert what it called its own looming pension crisis. Led by its newly elected treasurer, Gina Raimondo – an ostentatiously ambitious 42-year-old Rhodes scholar and former venture capitalist – the state declared war on public pensions, ramming through an ingenious new law slashing benefits of state employees with a speed and ferocity seldom before seen by any local government.

Called the Rhode Island Retirement Security Act of 2011, her plan would later be hailed as the most comprehensive pension reform ever implemented. The rap was so convincing at first that the overwhelmed local burghers of her little petri-dish state didn't even know how to react. "She's Yale, Harvard, Oxford – she worked on Wall Street," says Paul Doughty, the current president of the Providence firefighters union. "Nobody wanted to be the first to raise his hand and admit he didn't know what the fuck she was talking about."

Soon she was being talked about as a probable candidate for Rhode Island's 2014 gubernatorial race. By 2013, Raimondo had raised more than $2 million, a staggering sum for a still-undeclared candidate in a thimble-size state. Donors from Wall Street firms like Goldman Sachs, Bain Capital and JPMorgan Chase showered her with money, with more than $247,000 coming from New York contributors alone. A shadowy organization called EngageRI, a public-advocacy group of the 501(c)4 type whose donors were shielded from public scrutiny by the infamous Citizens United decision, spent $740,000 promoting Raimondo's ideas. Within Rhode Island, there began to be whispers that Raimondo had her sights on the presidency. Even former Obama right hand and Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel pointed to Rhode Island as an example to be followed in curing pension woes.

What few people knew at the time was that Raimondo's "tool kit" wasn't just meant for local consumption. The dynamic young Rhodes scholar was allowing her state to be used as a test case for the rest of the country, at the behest of powerful out-of-state financiers with dreams of pushing pension reform down the throats of taxpayers and public workers from coast to coast. One of her key supporters was billionaire former Enron executive John Arnold – a dickishly ubiquitous young right-wing kingmaker with clear designs on becoming the next generation's Koch brothers, and who for years had been funding a nationwide campaign to slash benefits for public workers.

Nor did anyone know that part of Raimondo's strategy for saving money involved handing more than $1 billion – 14 percent of the state fund – to hedge funds, including a trio of well-known New York-based funds: Dan Loeb's Third Point Capital was given $66 million, Ken Garschina's Mason Capital got $64 million and $70 million went to Paul Singer's Elliott Management. The funds now stood collectively to be paid tens of millions in fees every single year by the already overburdened taxpayers of her ostensibly flat-broke state. Felicitously, Loeb, Garschina and Singer serve on the board of the Manhattan Institute, a prominent conservative think tank with a history of supporting benefit-slashing reforms. The institute named Raimondo its 2011 "Urban Innovator" of the year.

The state's workers, in other words, were being forced to subsidize their own political disenfranchisement, coughing up at least $200 million to members of a group that had supported anti-labor laws. Later, when Edward Siedle, a former SEC lawyer, asked Raimondo in a column for Forbes.com how much the state was paying in fees to these hedge funds, she first claimed she didn't know. Raimondo later told the Providence Journal she was contractually obliged to defer to hedge funds on the release of "proprietary" information, which immediately prompted a letter in protest from a series of freaked-out interest groups. Under pressure, the state later released some fee information, but the information was originally kept hidden, even from the workers themselves. "When I asked, I was basically hammered," says Marcia Reback, a former sixth-grade schoolteacher and retired Providence Teachers Union president who serves as the lone union rep on Rhode Island's nine-member State Investment Commission. "I couldn't get any information about the actual costs."

This is the third act in an improbable triple-fucking of ordinary people that Wall Street is seeking to pull off as a shocker epilogue to the crisis era. Five years ago this fall, an epidemic of fraud and thievery in the financial-services industry triggered the collapse of our economy. The resultant loss of tax revenue plunged states everywhere into spiraling fiscal crises, and local governments suffered huge losses in their retirement portfolios – remember, these public pension funds were some of the most frequently targeted suckers upon whom Wall Street dumped its fraud-riddled mortgage-backed securities in the pre-crash years.

Today, the same Wall Street crowd that caused the crash is not merely rolling in money again but aggressively counterattacking on the public-relations front. The battle increasingly centers around public funds like state and municipal pensions. This war isn't just about money. Crucially, in ways invisible to most Americans, it's also about blame. In state after state, politicians are following the Rhode Island playbook, using scare tactics and lavishly funded PR campaigns to cast teachers, firefighters and cops – not bankers – as the budget-devouring boogeymen responsible for the mounting fiscal problems of America's states and cities.

Not only did these middle-class workers already lose huge chunks of retirement money to huckster financiers in the crash, and not only are they now being asked to take the long-term hit for those years of greed and speculative excess, but in many cases they're also being forced to sit by and watch helplessly as Gordon Gekko wanna-be's like Loeb or scorched-earth takeover artists like Bain Capital are put in charge of their retirement savings.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Democracy Now: Matt Taibbi on How Wall Street Hedge Funds Are Looting the Pension Funds of Public Workers

Matt Taibbi on How Wall Street Hedge Funds Are Looting the Pension Funds of Public Workers

Democracy Now

In his latest article for Rolling Stone, Matt Taibbi reports that Wall Street firms are now making millions in profits off of public pension funds nationwide. "Essentially it is a wealth transfer from teachers, cops and firemen to billionaire hedge funders," Taibbi says. "Pension funds are one of the last great, unguarded piles of money in this country and there are going to be all sort of operators that are trying to get their hands on that money."

To Watch the Episode

Democracy Now

In his latest article for Rolling Stone, Matt Taibbi reports that Wall Street firms are now making millions in profits off of public pension funds nationwide. "Essentially it is a wealth transfer from teachers, cops and firemen to billionaire hedge funders," Taibbi says. "Pension funds are one of the last great, unguarded piles of money in this country and there are going to be all sort of operators that are trying to get their hands on that money."

To Watch the Episode

Democracy Now: 40 Years After Secret U.S. War in Laos Ended, Millions of Unexploded Bomblets Keep Killing Laotians

40 Years After Secret U.S. War in Laos Ended, Millions of Unexploded Bomblets Keep Killing Laotians

Democracy Now

Forty years ago, on March 29, 1973, the "secret" U.S. bombing that devastated Laos came to an end. By that point, the United States had dropped at least two million tons of bombs on Laos. That is the equivalent of one planeload every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, for nine years — more than on Germany and Japan during World War II. The deadly legacy of the Vietnam War lives on today in the form of unexploded cluster bombs. Experts estimate Laos is littered with as many as 80 million "bombies" — or baseball-size bombs found inside cluster bombs. Since the bombing stopped four decades ago, as many as 20,000 people have been injured or killed as a result. To mark International Day of Mine Awareness, we speak to a Laotian bomb survivor and a leader of an all-women bomb clearance team in Laos. Thoummy Silamphan and Manixia Thor are speaking at the United Nations ... and are currently in the United States on a tour organized by Legacies of War.

GUESTS

Thoummy Silamphan, bomb accident survivor and victim assistance advocate in Laos.

Manixia Thor, leads an all-women bomb clearance team in Laos.

Channapha Khamvongsa, founder and executive director and founder of Legacies of War.

To Listen to This Episode

Democracy Now

Forty years ago, on March 29, 1973, the "secret" U.S. bombing that devastated Laos came to an end. By that point, the United States had dropped at least two million tons of bombs on Laos. That is the equivalent of one planeload every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, for nine years — more than on Germany and Japan during World War II. The deadly legacy of the Vietnam War lives on today in the form of unexploded cluster bombs. Experts estimate Laos is littered with as many as 80 million "bombies" — or baseball-size bombs found inside cluster bombs. Since the bombing stopped four decades ago, as many as 20,000 people have been injured or killed as a result. To mark International Day of Mine Awareness, we speak to a Laotian bomb survivor and a leader of an all-women bomb clearance team in Laos. Thoummy Silamphan and Manixia Thor are speaking at the United Nations ... and are currently in the United States on a tour organized by Legacies of War.

GUESTS

Thoummy Silamphan, bomb accident survivor and victim assistance advocate in Laos.

Manixia Thor, leads an all-women bomb clearance team in Laos.

Channapha Khamvongsa, founder and executive director and founder of Legacies of War.

To Listen to This Episode

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

Tuesday, September 24, 2013

Monday, September 23, 2013

Gary Younge: The American dream has become a burden for most

The American dream has become a burden for most

by Gary Younge

Comment is Free

As wages stagnate and costs rise, US workers recognise the guiding ideal of this nation for the delusional myth it is

The final chapter of America's Promise, a high-school textbook on American history, ends with a rallying cry to national mythology. "The history of the United States is one of challenges faced, problems resolved, and crises overcome," it states. "Throughout their history Americans have remained an optimistic people, carrying this optimism into the new century. The full promise of America has yet to be realised. This is the real promise of America; the ability to dream of a better world to come."

Such are the assumptions beamed from the torch of Lady Liberty, coursing through the veins of the nation's political culture and imbibed with mothers' milk. Their nation, many will tell you, is not just a land mass but an ideal – a shining city on the hill beckoning a bright new tomorrow and a dazzling dawn for all those who want it badly enough. Such devout optimism, even (and at times particularly) in the midst of adversity makes America, in equal parts, both exciting and delusional. According to Gallup, since 1977 people have consistently believed their financial situation will improve next year even when previous years have consistently been worse.

But when President Barack Obama was planning his run for a second term his pollsters noticed a profound shift in the national mood. The optimism was largely gone – and with it both the excitement and the delusion. The time-honoured rhetorical appeals to a life of relentless progress, upward mobility and personal reinvention didn't work the way they used to.

"The language around the American dream wasn't carrying the same resonance," Joel Benenson, one of Obama's key pollsters, told the Washington Post. "Some of the symbols of achieving the American dream were becoming burdens – owning that house with the big mortgage was expensive, owning two cars and more debts; having your kid go to college. The cost and burden of taking out those loans was making a lot of Americans ambivalent. They weren't sure a college education was worth it."

This wasn't just about the recession – though of course that didn't help – but a far more protracted, profound and painful descent in expectations and aspirations that has been taking place for several decades. For underpinning that faith in a better tomorrow was an understanding that inequality in wealth would be tolerated so long as it was coupled with a guarantee of equality of opportunity. In recent years they have seen both heading in the wrong direction – the gap between rich and poor has grown even as possibilities for economic and social advancement have stalled.

Between 2007 and 2010 the median American family lost a generation of wealth, putting them on a par with where they were in 1992. Last week the census revealed that median household income is roughly the same as it was in 1988 and that the poverty rate had actually increased since 1973. Meanwhile, median male earnings in 2010 were on a par with 1964. This is not for want of effort. American workers continue to make gains in productivity and American companies continue to reap the benefits. Last year corporate profits, as a share of the economy, were the highest since the second world war. The trouble is, none of the benefits went back to them.

To Read the Rest

by Gary Younge

Comment is Free

As wages stagnate and costs rise, US workers recognise the guiding ideal of this nation for the delusional myth it is

The final chapter of America's Promise, a high-school textbook on American history, ends with a rallying cry to national mythology. "The history of the United States is one of challenges faced, problems resolved, and crises overcome," it states. "Throughout their history Americans have remained an optimistic people, carrying this optimism into the new century. The full promise of America has yet to be realised. This is the real promise of America; the ability to dream of a better world to come."

Such are the assumptions beamed from the torch of Lady Liberty, coursing through the veins of the nation's political culture and imbibed with mothers' milk. Their nation, many will tell you, is not just a land mass but an ideal – a shining city on the hill beckoning a bright new tomorrow and a dazzling dawn for all those who want it badly enough. Such devout optimism, even (and at times particularly) in the midst of adversity makes America, in equal parts, both exciting and delusional. According to Gallup, since 1977 people have consistently believed their financial situation will improve next year even when previous years have consistently been worse.

But when President Barack Obama was planning his run for a second term his pollsters noticed a profound shift in the national mood. The optimism was largely gone – and with it both the excitement and the delusion. The time-honoured rhetorical appeals to a life of relentless progress, upward mobility and personal reinvention didn't work the way they used to.

"The language around the American dream wasn't carrying the same resonance," Joel Benenson, one of Obama's key pollsters, told the Washington Post. "Some of the symbols of achieving the American dream were becoming burdens – owning that house with the big mortgage was expensive, owning two cars and more debts; having your kid go to college. The cost and burden of taking out those loans was making a lot of Americans ambivalent. They weren't sure a college education was worth it."

This wasn't just about the recession – though of course that didn't help – but a far more protracted, profound and painful descent in expectations and aspirations that has been taking place for several decades. For underpinning that faith in a better tomorrow was an understanding that inequality in wealth would be tolerated so long as it was coupled with a guarantee of equality of opportunity. In recent years they have seen both heading in the wrong direction – the gap between rich and poor has grown even as possibilities for economic and social advancement have stalled.

Between 2007 and 2010 the median American family lost a generation of wealth, putting them on a par with where they were in 1992. Last week the census revealed that median household income is roughly the same as it was in 1988 and that the poverty rate had actually increased since 1973. Meanwhile, median male earnings in 2010 were on a par with 1964. This is not for want of effort. American workers continue to make gains in productivity and American companies continue to reap the benefits. Last year corporate profits, as a share of the economy, were the highest since the second world war. The trouble is, none of the benefits went back to them.

To Read the Rest

Democracy Now - Spilling the NSA’s Secrets: Guardian Editor Alan Rusbridger on the Inside Story of Snowden Leaks

Spilling the NSA’s Secrets: Guardian Editor Alan Rusbridger on the Inside Story of Snowden Leaks

Democracy Now

Three-and-a-half months after National Security Agency leaker Edward Snowden came public on the the U.S. government’s massive spying operations at home and abroad, we spend the hour with Alan Rusbridger, editor-in-chief of The Guardian, the British newspaper that first reported on Snowden’s leaked documents. The Guardian has continued releasing a series of exposés based on Snowden’s leaks coloring in the details on how the NSA has managed to collect telephone records in bulk and information on nearly everything a user does on the Internet. The articles have ignited widespread debate about security agencies’ covert activities, digital data protection and the nature of investigative journalism. The newspaper has been directly targeted as a result — over the summer the British government forced the paper to destroy computer hard drives containing copies of Snowden’s secret files, and later detained David Miranda, the partner of Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald. Rusbridger, editor of The Guardian for nearly two decades, joins us to tell the inside story of The Guardian’s publication of the NSA leaks and the crackdown it has faced from its own government as a result.

To Watch the Episode

Democracy Now

Three-and-a-half months after National Security Agency leaker Edward Snowden came public on the the U.S. government’s massive spying operations at home and abroad, we spend the hour with Alan Rusbridger, editor-in-chief of The Guardian, the British newspaper that first reported on Snowden’s leaked documents. The Guardian has continued releasing a series of exposés based on Snowden’s leaks coloring in the details on how the NSA has managed to collect telephone records in bulk and information on nearly everything a user does on the Internet. The articles have ignited widespread debate about security agencies’ covert activities, digital data protection and the nature of investigative journalism. The newspaper has been directly targeted as a result — over the summer the British government forced the paper to destroy computer hard drives containing copies of Snowden’s secret files, and later detained David Miranda, the partner of Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald. Rusbridger, editor of The Guardian for nearly two decades, joins us to tell the inside story of The Guardian’s publication of the NSA leaks and the crackdown it has faced from its own government as a result.

To Watch the Episode

Henry Porter: American gun use is out of control. Shouldn't the world intervene?

American gun use is out of control. Shouldn't the world intervene?

Comment is Free

by Henry Porter

The death toll from firearms in the US suggests that the country is gripped by civil war

Last week, Starbucks asked its American customers to please not bring their guns into the coffee shop. This is part of the company's concern about customer safety and follows a ban in the summer on smoking within 25 feet of a coffee shop entrance and an earlier ruling about scalding hot coffee. After the celebrated Liebeck v McDonald's case in 1994, involving a woman who suffered third-degree burns to her thighs, Starbucks complies with the Specialty Coffee Association of America's recommendation that drinks should be served at a maximum temperature of 82C.

Although it was brave of Howard Schultz, the company's chief executive, to go even this far in a country where people are better armed and only slightly less nervy than rebel fighters in Syria, we should note that dealing with the risks of scalding and secondary smoke came well before addressing the problem of people who go armed to buy a latte. There can be no weirder order of priorities on this planet.

That's America, we say, as news of the latest massacre breaks – last week it was the slaughter of 12 people by Aaron Alexis at Washington DC's navy yard – and move on. But what if we no longer thought of this as just a problem for America and, instead, viewed it as an international humanitarian crisis – a quasi civil war, if you like, that calls for outside intervention? As citizens of the world, perhaps we should demand an end to the unimaginable suffering of victims and their families – the maiming and killing of children – just as America does in every new civil conflict around the globe.

The annual toll from firearms in the US is running at 32,000 deaths and climbing, even though the general crime rate is on a downward path (it is 40% lower than in 1980). If this perennial slaughter doesn't qualify for intercession by the UN and all relevant NGOs, it is hard to know what does.

To absorb the scale of the mayhem, it's worth trying to guess the death toll of all the wars in American history since the War of Independence began in 1775, and follow that by estimating the number killed by firearms in the US since the day that Robert F. Kennedy was shot in 1968 by a .22 Iver-Johnson handgun, wielded by Sirhan Sirhan. The figures from Congressional Research Service, plus recent statistics from icasualties.org, tell us that from the first casualties in the battle of Lexington to recent operations in Afghanistan, the toll is 1,171,177. By contrast, the number killed by firearms, including suicides, since 1968, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and the FBI, is 1,384,171.

To Read the Rest

Comment is Free

by Henry Porter

The death toll from firearms in the US suggests that the country is gripped by civil war

Last week, Starbucks asked its American customers to please not bring their guns into the coffee shop. This is part of the company's concern about customer safety and follows a ban in the summer on smoking within 25 feet of a coffee shop entrance and an earlier ruling about scalding hot coffee. After the celebrated Liebeck v McDonald's case in 1994, involving a woman who suffered third-degree burns to her thighs, Starbucks complies with the Specialty Coffee Association of America's recommendation that drinks should be served at a maximum temperature of 82C.

Although it was brave of Howard Schultz, the company's chief executive, to go even this far in a country where people are better armed and only slightly less nervy than rebel fighters in Syria, we should note that dealing with the risks of scalding and secondary smoke came well before addressing the problem of people who go armed to buy a latte. There can be no weirder order of priorities on this planet.

That's America, we say, as news of the latest massacre breaks – last week it was the slaughter of 12 people by Aaron Alexis at Washington DC's navy yard – and move on. But what if we no longer thought of this as just a problem for America and, instead, viewed it as an international humanitarian crisis – a quasi civil war, if you like, that calls for outside intervention? As citizens of the world, perhaps we should demand an end to the unimaginable suffering of victims and their families – the maiming and killing of children – just as America does in every new civil conflict around the globe.

The annual toll from firearms in the US is running at 32,000 deaths and climbing, even though the general crime rate is on a downward path (it is 40% lower than in 1980). If this perennial slaughter doesn't qualify for intercession by the UN and all relevant NGOs, it is hard to know what does.

To absorb the scale of the mayhem, it's worth trying to guess the death toll of all the wars in American history since the War of Independence began in 1775, and follow that by estimating the number killed by firearms in the US since the day that Robert F. Kennedy was shot in 1968 by a .22 Iver-Johnson handgun, wielded by Sirhan Sirhan. The figures from Congressional Research Service, plus recent statistics from icasualties.org, tell us that from the first casualties in the battle of Lexington to recent operations in Afghanistan, the toll is 1,171,177. By contrast, the number killed by firearms, including suicides, since 1968, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and the FBI, is 1,384,171.

To Read the Rest

Saturday, September 21, 2013

On the Media: The Surprising History of Gun Control, School Shooting Myths, and More

The Surprising History of Gun Control, School Shooting Myths, and More

On the Media

The surprising history of the gun control narrative, the media myths of past school shootings, and the problem when the media speculate on the mental health of shooters.

We’ve become accustomed in the past 20 years to seeing the issue of guns in America broken down into two camps: gun control advocates — led by police chiefs and Sarah Brady — and the all-powerful National Rifle Association. Bob talks to Adam Winkler, author of Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms In America, who says there was a time, relatively recently, in fact, when the NRA Supported gun control legislation, and the staunchest defenders of so-called "gun rights" were on the radical left.

How Myths Form After a School Shooting

The press has misreported a lot about the Newtown shooting, and if history is any guide, much of that misreporting will inform our memory of the event. In his book Columbine, Dave Cullen revisited that soul shattering school shooting 13 years ago. He tells Bob that our story of that event is largely frozen in early misreporting.

Speculating about Adam Lanza's Mind

Once Adam Lanza had been correctly identified as the shooter, speculation quickly turned to why he killed so many. Much of the media raced, as it often does, to explain the tragedy by speculating on Lanza’s psychological state. Particularly bandied about was whether Lanza had been diagnosed with either a personality disorder or Asperger’s Syndrome. Bob talks with the Columbia Journalism Review's Curtis Brainard about the perils of this sort of coverage.

Interviewing Kids In the Wake of a Tragedy

A lot of criticism was leveled at the press for interviewing the child survivors of the Newtown school shooting in its immediate aftermath. Bob talks to WABC-TV reporter Bill Ritter about whether it's ever appropriate to interview a child in the moments after a disaster of this nature, and whether the very act of interviewing a child could contribute to the childrens' trauma.

Politicizing the Congressional Research Service

Last week, the Congressional Research Service released an updated version of a report that repudiates a mainstay of conservative economic doctrine: namely, that reducing top marginal tax rates spurs economic growth. Despite the CRS's bipartisan track record, and despite the report's potentially explosive implications for the ongoing "fiscal cliff" debate, the media have barely paid it any attention. Roll Call reporter Emma Dumain talks with Bob about the peculiar role of the CRS as a non-partisan football in a fiercely partisan game.

To Bork

Supreme Court nominee and Constitutional originalist Robert Bork died this week at the age of 85. In a segment that originally aired in 2005, Brooke muses over the verb "to bork," coined in honor of the man whose unsuccessful bid for the bench earned him a place in Webster's.

The Great Newspaper Strike of 1962-63

Fifty years ago this month, 17,000 New York City newspaper workers went on strike, shuttering the city's seven daily papers for 114 days. Rooted in fears about new "cold type" printing technology, the strike ended up devastating the city's newspaper culture and launching the careers of a new generation of writers including Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, and Nora Ephron. Vanity Fair contributor Scott Sherman talks with Bob about the strike and its legacy.

TURNING DOWN LOUD COMMERCIALS

In 2010, Congress passed the Commercial Advertising Loudness Mitigation Act, also known as the CALM Act, which would keep television commercials from being louder than the programs they sponsor. The law finally went into effect last week. In an interview originally aired in 2010, the Wall Street Journal’s Elizabeth Williamson explains to Bob why regulators haven't been able to turn down the volume of commercials until now.

To Listen to the Show

On the Media

The surprising history of the gun control narrative, the media myths of past school shootings, and the problem when the media speculate on the mental health of shooters.

We’ve become accustomed in the past 20 years to seeing the issue of guns in America broken down into two camps: gun control advocates — led by police chiefs and Sarah Brady — and the all-powerful National Rifle Association. Bob talks to Adam Winkler, author of Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms In America, who says there was a time, relatively recently, in fact, when the NRA Supported gun control legislation, and the staunchest defenders of so-called "gun rights" were on the radical left.

How Myths Form After a School Shooting

The press has misreported a lot about the Newtown shooting, and if history is any guide, much of that misreporting will inform our memory of the event. In his book Columbine, Dave Cullen revisited that soul shattering school shooting 13 years ago. He tells Bob that our story of that event is largely frozen in early misreporting.

Speculating about Adam Lanza's Mind

Once Adam Lanza had been correctly identified as the shooter, speculation quickly turned to why he killed so many. Much of the media raced, as it often does, to explain the tragedy by speculating on Lanza’s psychological state. Particularly bandied about was whether Lanza had been diagnosed with either a personality disorder or Asperger’s Syndrome. Bob talks with the Columbia Journalism Review's Curtis Brainard about the perils of this sort of coverage.

Interviewing Kids In the Wake of a Tragedy

A lot of criticism was leveled at the press for interviewing the child survivors of the Newtown school shooting in its immediate aftermath. Bob talks to WABC-TV reporter Bill Ritter about whether it's ever appropriate to interview a child in the moments after a disaster of this nature, and whether the very act of interviewing a child could contribute to the childrens' trauma.

Politicizing the Congressional Research Service

Last week, the Congressional Research Service released an updated version of a report that repudiates a mainstay of conservative economic doctrine: namely, that reducing top marginal tax rates spurs economic growth. Despite the CRS's bipartisan track record, and despite the report's potentially explosive implications for the ongoing "fiscal cliff" debate, the media have barely paid it any attention. Roll Call reporter Emma Dumain talks with Bob about the peculiar role of the CRS as a non-partisan football in a fiercely partisan game.

To Bork

Supreme Court nominee and Constitutional originalist Robert Bork died this week at the age of 85. In a segment that originally aired in 2005, Brooke muses over the verb "to bork," coined in honor of the man whose unsuccessful bid for the bench earned him a place in Webster's.

The Great Newspaper Strike of 1962-63

Fifty years ago this month, 17,000 New York City newspaper workers went on strike, shuttering the city's seven daily papers for 114 days. Rooted in fears about new "cold type" printing technology, the strike ended up devastating the city's newspaper culture and launching the careers of a new generation of writers including Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, and Nora Ephron. Vanity Fair contributor Scott Sherman talks with Bob about the strike and its legacy.

TURNING DOWN LOUD COMMERCIALS

In 2010, Congress passed the Commercial Advertising Loudness Mitigation Act, also known as the CALM Act, which would keep television commercials from being louder than the programs they sponsor. The law finally went into effect last week. In an interview originally aired in 2010, the Wall Street Journal’s Elizabeth Williamson explains to Bob why regulators haven't been able to turn down the volume of commercials until now.

To Listen to the Show

Thursday, September 19, 2013

David Pinder: The Power and Politics of Maps

How can the power and politics of maps be uncovered, given their common mask of neutrality? A starting point is to approach maps as texts and a form of language. Maps employ rhetorical devices to make statements about the world, advancing particular propositions and arguments. Interpretation therefore entails decoding that language in terms of the visible as well as hidden codes, signs, rules and conventions through which maps are constructed. It is not a case of trying to expose how maps are somehow ‘wrong’ or ‘untrue.’ Such a stance assumes that it is possible to produce a value-free image that leaves an external world ‘undistorted.’ As I have argued, that claim is untenable. More to the point for the position that I am advocating here is to analyse how claims to truth or the truth-effects’ of maps are constituted, to address how they are part of a discourse of cartography through which they derive their authority and work as a form of knowledge and of power (175).

Pinder, David. “Mapping Worlds: Cartography and the Politics of Representation.” Cultural Geography in Practice. Ed. Alison Blunt, et al. NY: Oxford UP, 2003: 172-187.

Pinder, David. “Mapping Worlds: Cartography and the Politics of Representation.” Cultural Geography in Practice. Ed. Alison Blunt, et al. NY: Oxford UP, 2003: 172-187.

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Daniel Kovalik: Death of an Adjunct

Death of an adjunct

by Daniel Kovalik

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

On Sept. 1, Margaret Mary Vojtko, an adjunct professor who had taught French at Duquesne University for 25 years, passed away at the age of 83. She died as the result of a massive heart attack she suffered two weeks before. As it turned out, I may have been the last person she talked to.

On Aug. 16, I received a call from a very upset Margaret Mary. She told me that she was under an incredible amount of stress. She was receiving radiation therapy for the cancer that had just returned to her, she was living nearly homeless because she could not afford the upkeep on her home, which was literally falling in on itself, and now, she explained, she had received another indignity -- a letter from Adult Protective Services telling her that someone had referred her case to them saying that she needed assistance in taking care of herself. The letter said that if she did not meet with the caseworker the following Monday, her case would be turned over to Orphans' Court.

For a proud professional like Margaret Mary, this was the last straw; she was mortified. She begged me to call Adult Protective Services and tell them to leave her alone, that she could take care of herself and did not need their help. I agreed to. Sadly, a couple of hours later, she was found on her front lawn, unconscious from a heart attack. She never regained consciousness.

Meanwhile, I called Adult Protective Services right after talking to Margaret Mary, and I explained the situation. I said that she had just been let go from her job as a professor at Duquesne, that she was given no severance or retirement benefits, and that the reason she was having trouble taking care of herself was because she was living in extreme poverty. The caseworker paused and asked with incredulity, "She was a professor?" I said yes. The case- worker was shocked; this was not the usual type of person for whom she was called in to help.

Of course, what the case-worker didn't understand was that Margaret Mary was an adjunct professor, meaning that, unlike a well-paid tenured professor, Margaret Mary worked on a contract basis from semester to semester, with no job security, no benefits and with a salary of between $3,000 and just over $3,500 per three-credit course. Adjuncts now make up well over 50 percent of the faculty at colleges and universities.

To Read the Rest

by Daniel Kovalik

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

On Sept. 1, Margaret Mary Vojtko, an adjunct professor who had taught French at Duquesne University for 25 years, passed away at the age of 83. She died as the result of a massive heart attack she suffered two weeks before. As it turned out, I may have been the last person she talked to.

On Aug. 16, I received a call from a very upset Margaret Mary. She told me that she was under an incredible amount of stress. She was receiving radiation therapy for the cancer that had just returned to her, she was living nearly homeless because she could not afford the upkeep on her home, which was literally falling in on itself, and now, she explained, she had received another indignity -- a letter from Adult Protective Services telling her that someone had referred her case to them saying that she needed assistance in taking care of herself. The letter said that if she did not meet with the caseworker the following Monday, her case would be turned over to Orphans' Court.

For a proud professional like Margaret Mary, this was the last straw; she was mortified. She begged me to call Adult Protective Services and tell them to leave her alone, that she could take care of herself and did not need their help. I agreed to. Sadly, a couple of hours later, she was found on her front lawn, unconscious from a heart attack. She never regained consciousness.

Meanwhile, I called Adult Protective Services right after talking to Margaret Mary, and I explained the situation. I said that she had just been let go from her job as a professor at Duquesne, that she was given no severance or retirement benefits, and that the reason she was having trouble taking care of herself was because she was living in extreme poverty. The caseworker paused and asked with incredulity, "She was a professor?" I said yes. The case- worker was shocked; this was not the usual type of person for whom she was called in to help.

Of course, what the case-worker didn't understand was that Margaret Mary was an adjunct professor, meaning that, unlike a well-paid tenured professor, Margaret Mary worked on a contract basis from semester to semester, with no job security, no benefits and with a salary of between $3,000 and just over $3,500 per three-credit course. Adjuncts now make up well over 50 percent of the faculty at colleges and universities.

To Read the Rest

Dean Spade & Craig Willse: Marriage Will Never Set Us Free; John Scagliotti -- Why Gay Marriage Matters: A Reply to Dean Spade and Craig Willse

Marriage Will Never Set Us Free

by Dean Spade & Craig Willse

Organizing Upgrade

In recent years, lots of progressive people have been celebrating marriage -- when various states have passed laws recognizing same-sex marriage, when courts have made decisions affirming the legal recognition of same-sex marriage, when politicians have spoken in favor of it. At the same time, many queer activists and scholars have relentlessly critiqued same-sex marriage advocacy. Supporters of marriage sometimes acknowledge those critiques, and respond with something like: While marriage is not for everyone, and won’t solve everything, we still need it.

What’s the deal? Is same-sex marriage advocacy a progressive cause? Is it in line with Left political projects of racial and economic justice, decolonization, and feminist liberation?

Nope. Same-sex marriage advocacy has accomplished an amazing feat--it has made being anti-homophobic synonymous with being pro-marriage. It has drowned out centuries of critical thinking and activism against the racialized, colonial, and patriarchal processes of state regulation of family and gender through marriage. It is to such an understanding of marriage we first turn.

I. What is Marriage?

Civil marriage is a tool of social control used by governments to regulate sexuality and family formation by establishing a favored form and rewarding it (in the U.S., for example, with over one thousand benefits). While marriage is being rewarded, other ways of organizing family, relationships and sexual behavior do not receive these benefits and are stigmatized and criminalized. In short, people are punished or rewarded based on whether or not they marry. The idea that same-sex marriage advocacy is a fight for the “freedom to marry” or “equality” is absurd since the existence of legal marriage is a form of coercive regulation in which achieving or not achieving marital status is linked to accessing vital life resources like health care and paths to legalized immigration. There is nothing freeing nor equalizing about such a system.

In her famous 1984 essay, “Thinking Sex,” Gayle Rubin described how systems that hierarchically rank sexual practices change as part of maintaining their operations of control. Rubin described how sexuality is divided into those practices that are considered normal and natural--what she called the “charmed circle”-- and those that are considered bad and abnormal--the “outer limits.”

Practices can and do cross from the outer limits to the charmed circle. Unmarried couples living together, or perhaps homosexuality when it is monogamous and married, can move from being highly stigmatized to being considered acceptable. These shifts, however, do not eliminate the ranking of sexual behaviors; in other words, these shifts do not challenge the existence of a charmed circle and outer limits in the first place. Freedom and equality are not achieved when a practice crosses over to being acceptable. Instead, such shifts strengthen the line between what is considered good, healthy, and normal and what remains bad, unhealthy, stigmatized, and criminalized. The line moves to accommodate a few more people, who society suddenly approves of, correcting the system and keeping it in place. The legal marriage system--along with its corollary criminal punishment system, with its laws against lewd behavior, solicitation, indecency and the like-- enforces the line between which sexual practices and behaviors are acceptable and rewarded, and which are contemptible and even punishable.

Societal myths about marriage, which are replicated in same-sex marriage advocacy, tell us that marriage is about love, about care for elders and children, about sharing the good life together--even that it is the cornerstone of a happy personal life and a healthy civilization. Feminist, anti-racist, and anti-colonial social movements have contested this, identifying marriage as a system that violently enforces sexual and familial norms. From these social movements, we understand marriage as a technology of social control, exploitation, and dispossession wrapped in a satin ribbon of sexist and heteropatriarchal romance mythology.

To Read the Rest

More:

John Scagliotti -- Why Gay Marriage Matters: A Reply to Dean Spade and Craig Willse (Organizing Upgrade)

by Dean Spade & Craig Willse

Organizing Upgrade

In recent years, lots of progressive people have been celebrating marriage -- when various states have passed laws recognizing same-sex marriage, when courts have made decisions affirming the legal recognition of same-sex marriage, when politicians have spoken in favor of it. At the same time, many queer activists and scholars have relentlessly critiqued same-sex marriage advocacy. Supporters of marriage sometimes acknowledge those critiques, and respond with something like: While marriage is not for everyone, and won’t solve everything, we still need it.

What’s the deal? Is same-sex marriage advocacy a progressive cause? Is it in line with Left political projects of racial and economic justice, decolonization, and feminist liberation?

Nope. Same-sex marriage advocacy has accomplished an amazing feat--it has made being anti-homophobic synonymous with being pro-marriage. It has drowned out centuries of critical thinking and activism against the racialized, colonial, and patriarchal processes of state regulation of family and gender through marriage. It is to such an understanding of marriage we first turn.

I. What is Marriage?

Civil marriage is a tool of social control used by governments to regulate sexuality and family formation by establishing a favored form and rewarding it (in the U.S., for example, with over one thousand benefits). While marriage is being rewarded, other ways of organizing family, relationships and sexual behavior do not receive these benefits and are stigmatized and criminalized. In short, people are punished or rewarded based on whether or not they marry. The idea that same-sex marriage advocacy is a fight for the “freedom to marry” or “equality” is absurd since the existence of legal marriage is a form of coercive regulation in which achieving or not achieving marital status is linked to accessing vital life resources like health care and paths to legalized immigration. There is nothing freeing nor equalizing about such a system.

In her famous 1984 essay, “Thinking Sex,” Gayle Rubin described how systems that hierarchically rank sexual practices change as part of maintaining their operations of control. Rubin described how sexuality is divided into those practices that are considered normal and natural--what she called the “charmed circle”-- and those that are considered bad and abnormal--the “outer limits.”

Practices can and do cross from the outer limits to the charmed circle. Unmarried couples living together, or perhaps homosexuality when it is monogamous and married, can move from being highly stigmatized to being considered acceptable. These shifts, however, do not eliminate the ranking of sexual behaviors; in other words, these shifts do not challenge the existence of a charmed circle and outer limits in the first place. Freedom and equality are not achieved when a practice crosses over to being acceptable. Instead, such shifts strengthen the line between what is considered good, healthy, and normal and what remains bad, unhealthy, stigmatized, and criminalized. The line moves to accommodate a few more people, who society suddenly approves of, correcting the system and keeping it in place. The legal marriage system--along with its corollary criminal punishment system, with its laws against lewd behavior, solicitation, indecency and the like-- enforces the line between which sexual practices and behaviors are acceptable and rewarded, and which are contemptible and even punishable.

Societal myths about marriage, which are replicated in same-sex marriage advocacy, tell us that marriage is about love, about care for elders and children, about sharing the good life together--even that it is the cornerstone of a happy personal life and a healthy civilization. Feminist, anti-racist, and anti-colonial social movements have contested this, identifying marriage as a system that violently enforces sexual and familial norms. From these social movements, we understand marriage as a technology of social control, exploitation, and dispossession wrapped in a satin ribbon of sexist and heteropatriarchal romance mythology.

To Read the Rest

More:

John Scagliotti -- Why Gay Marriage Matters: A Reply to Dean Spade and Craig Willse (Organizing Upgrade)

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Law and Disorder Radio: Mara Verheyden-Hilliard - FBI Considers The Occupy Movement A Terrorist Threat: The State of Civil Rights and Public Policy; Carl Mayer - Challenging The National Defense Authorization Act of 2012

Law and Disorder Radio

FBI Considers The Occupy Movement A Terrorist Threat: The State of Civil Rights and Public Policy

A few weeks ago the Partnership for Civil Justice Fund released secret documents obtained by Freedom of Information Act requests revealing that the Occupy movement was treated as a terrorist threat by the FBI. This is despite agency acknowledgement that the organizers called for peaceful protests. The documents also show massive resources used to track the Occupy movement, a month prior to the encampment in Zuccotti Park. FBI and counter-terrorism agents in offices across the country, from Anchorage to Jacksonville, to Tampa, Virginia, Milwaukee, Birmingham, Memphis and Denver, coordinated with various local and federal law enforcement, to monitor and collect intelligence on OWS. The documents obtained by the PCJF are heavily redacted and the tip of the ice berg says our guest attorney Mara Verheyden Hilliard. We also talk with Mara about her thoughts on the state of civil rights for the year moving forward.

Guest – Mara Verheyden-Hilliard, co-chair of the National Lawyers Guild’s national Mass Defense Committee. Co-founder of the Partnership for Civil Justice Fund in Washington, DC, she recently secured $13.7 million for about 700 of the 2000 IMF/World Bank protesters in Becker, et al. v. District of Columbia, et al., while also winning pledges from the District to improve police training about First Amendment issues. She won $8.25 million for approximately 400 class members in Barham, et al. v. Ramsey, et al. (alleging false arrest at the 2002 IMF/World Bank protests). She served as lead counsel in Mills, et al v. District of Columbia (obtaining a ruling that D.C.’s seizure and interrogation police checkpoint program was unconstitutional); in Bolger, et al. v. District of Columbia (involving targeting of political activists and false arrest by law enforcement based on political affiliation); and in National Council of Arab Americans, et al. v. City of New York, et al. (successfully challenging the city’s efforts to discriminatorily restrict mass assembly in Central Park’s Great Lawn stemming from the 2004 RNC protests.)

Challenging The National Defense Authorization Act of 2012

Last September a federal judge struck down part of the National Defense Authorization Act signed by President Obama that gave the government power to indefinitely detain anyone, anywhere in the world it considers to substantially support or be in associative force with terrorism. This includes US citizens. Judge Katherine Forrest of the Southern District of New York had ruled the indefinite detention provision of the National Defense Authorization Act likely violates the First and Fifth Amendments of U.S. citizens.

Guest – Attorney Carl Mayer runs the Mayer Law Group LLC and is the author of several books including “Shakedown” and “Public Domain, Private Dominion.” Carl Mayer is a former law professor and served as special counsel to the New York State Attorney General.

To Listen to the Episode

FBI Considers The Occupy Movement A Terrorist Threat: The State of Civil Rights and Public Policy

A few weeks ago the Partnership for Civil Justice Fund released secret documents obtained by Freedom of Information Act requests revealing that the Occupy movement was treated as a terrorist threat by the FBI. This is despite agency acknowledgement that the organizers called for peaceful protests. The documents also show massive resources used to track the Occupy movement, a month prior to the encampment in Zuccotti Park. FBI and counter-terrorism agents in offices across the country, from Anchorage to Jacksonville, to Tampa, Virginia, Milwaukee, Birmingham, Memphis and Denver, coordinated with various local and federal law enforcement, to monitor and collect intelligence on OWS. The documents obtained by the PCJF are heavily redacted and the tip of the ice berg says our guest attorney Mara Verheyden Hilliard. We also talk with Mara about her thoughts on the state of civil rights for the year moving forward.

Guest – Mara Verheyden-Hilliard, co-chair of the National Lawyers Guild’s national Mass Defense Committee. Co-founder of the Partnership for Civil Justice Fund in Washington, DC, she recently secured $13.7 million for about 700 of the 2000 IMF/World Bank protesters in Becker, et al. v. District of Columbia, et al., while also winning pledges from the District to improve police training about First Amendment issues. She won $8.25 million for approximately 400 class members in Barham, et al. v. Ramsey, et al. (alleging false arrest at the 2002 IMF/World Bank protests). She served as lead counsel in Mills, et al v. District of Columbia (obtaining a ruling that D.C.’s seizure and interrogation police checkpoint program was unconstitutional); in Bolger, et al. v. District of Columbia (involving targeting of political activists and false arrest by law enforcement based on political affiliation); and in National Council of Arab Americans, et al. v. City of New York, et al. (successfully challenging the city’s efforts to discriminatorily restrict mass assembly in Central Park’s Great Lawn stemming from the 2004 RNC protests.)

Challenging The National Defense Authorization Act of 2012

Last September a federal judge struck down part of the National Defense Authorization Act signed by President Obama that gave the government power to indefinitely detain anyone, anywhere in the world it considers to substantially support or be in associative force with terrorism. This includes US citizens. Judge Katherine Forrest of the Southern District of New York had ruled the indefinite detention provision of the National Defense Authorization Act likely violates the First and Fifth Amendments of U.S. citizens.

Guest – Attorney Carl Mayer runs the Mayer Law Group LLC and is the author of several books including “Shakedown” and “Public Domain, Private Dominion.” Carl Mayer is a former law professor and served as special counsel to the New York State Attorney General.

To Listen to the Episode

Marshall Berman (November 24, 1940 – September 11, 2013)

Marshall Berman, Philosopher Who Praised Marx and Modernism, Dies at 72

By William Yardley

The New York Times

Marshall Berman, an author, academic, philosopher and lyrical defender of modernism, Karl Marx and his native New York City, died on Wednesday in Manhattan. He was 72.

His death was announced by City College, where Dr. Berman had taught since 1967 and was distinguished professor of political science. His son Danny said Dr. Berman had a heart attack while eating breakfast with a friend at a diner he loved, the Metro Diner on Broadway and 100th Street.

Dr. Berman was a public intellectual and often an optimistic one. He heard song in conflict and argued that the stop-start stumble of modern life was, for all its inexplicability and despair, necessary and promising. Marx, he insisted counterintuitively, might admire the energy and diversity that capitalism has delivered to the United States even if he believed there was a better way. The Bronx, Times Square, all of New York in its many incarnations — from the seedy, bankrupt 1970s to the murderous 1980s to today’s urban boutique — was in his view alive and luminous in its recklessness and resilience.

“Something is happening that I never could have imagined: a metropolitan life with a level of dread that is subsiding,” he wrote in an introductory essay to the 2007 book “New York Calling: From Blackout to Bloomberg,” which he edited with Brian Berger. “Some people say they’re worried that a life without dread will lose its savor. I tell my students and people I know not to worry. If they just scrutinize their lives, they will find grounds for more than enough dread to keep them awake. While they’re up, they should seize the day and take a midnight walk.”

Dr. Berman arrived at City College shortly after he finished his doctoral studies at Harvard. But he was not interested in academic solitude. Devoted to the university’s missions of diversity and accessibility, he passed up chances to move to Ivy League schools or colleges in the West.

Inside the kitchen cupboards of the Upper West Side apartment where he lived for decades, he stored his staples: books. Inside the bathroom cabinets, he stored his balm: more books.

His intellectual passion was first stirred by Marx — with his shaggy hair and beard, he eventually started looking like him — and he viewed Marx as deeply relevant long after Communist governments faded.

“Marx was appalled at the human costs of capitalist development,” Dr. Berman wrote in the introduction to the Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition of Marx’s “Communist Manifesto,” published in 2011, “but he always believed the world horizon it created was a great human achievement, on which socialist and communist movements must build. Remember, the grand appeal to unite, with which the Manifesto ends, is addressed to the ‘workers of all countries.’ ”

Dr. Berman’s best-known book, “All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity,” was published in 1982 and took its name from a line in the Manifesto. Reviewing it in The New York Times, John Leonard called it “brilliant and exasperating.”

“Being modern is being new, whether we like it or not,” Mr. Leonard wrote, summarizing his assessment of Dr. Berman’s argument. “He likes it, Mr. Berman. Seize the day and change the world. Modernism is ‘a permanent revolution,’ full of radical sunrise and great dawn. We synthesize ourselves, without tears.”

Mr. Leonard added: “I’ve read Goethe, Marx, Baudelaire and Dostoyevsky, and I’ve been to Leningrad. Mr. Berman, generous and exuberant and dazzling, has been somewhere else, with a ‘shadow passport,’ inventing another history and literature, a romance of great ideas. I love this book and wish that I believed it.”

Marshall Howard Berman was born on Nov. 24, 1940, in the Bronx. His parents, Murray and Betty, ran a tag and label business in Times Square. His father died when his son was 14. Dr. Berman grew up taking the subway with his family to Times Square, a lifelong stimulant he celebrated in his 2006 book, “On the Town: One Hundred Years of Spectacle in Times Square.”

To Read the Rest

To Read All That Is Solid Melts Into the Air

More:

Marianna Reis: Marshall Berman, 1940-2013 (Verso)

By William Yardley

The New York Times

Marshall Berman, an author, academic, philosopher and lyrical defender of modernism, Karl Marx and his native New York City, died on Wednesday in Manhattan. He was 72.

His death was announced by City College, where Dr. Berman had taught since 1967 and was distinguished professor of political science. His son Danny said Dr. Berman had a heart attack while eating breakfast with a friend at a diner he loved, the Metro Diner on Broadway and 100th Street.

Dr. Berman was a public intellectual and often an optimistic one. He heard song in conflict and argued that the stop-start stumble of modern life was, for all its inexplicability and despair, necessary and promising. Marx, he insisted counterintuitively, might admire the energy and diversity that capitalism has delivered to the United States even if he believed there was a better way. The Bronx, Times Square, all of New York in its many incarnations — from the seedy, bankrupt 1970s to the murderous 1980s to today’s urban boutique — was in his view alive and luminous in its recklessness and resilience.

“Something is happening that I never could have imagined: a metropolitan life with a level of dread that is subsiding,” he wrote in an introductory essay to the 2007 book “New York Calling: From Blackout to Bloomberg,” which he edited with Brian Berger. “Some people say they’re worried that a life without dread will lose its savor. I tell my students and people I know not to worry. If they just scrutinize their lives, they will find grounds for more than enough dread to keep them awake. While they’re up, they should seize the day and take a midnight walk.”

Dr. Berman arrived at City College shortly after he finished his doctoral studies at Harvard. But he was not interested in academic solitude. Devoted to the university’s missions of diversity and accessibility, he passed up chances to move to Ivy League schools or colleges in the West.

Inside the kitchen cupboards of the Upper West Side apartment where he lived for decades, he stored his staples: books. Inside the bathroom cabinets, he stored his balm: more books.

His intellectual passion was first stirred by Marx — with his shaggy hair and beard, he eventually started looking like him — and he viewed Marx as deeply relevant long after Communist governments faded.

“Marx was appalled at the human costs of capitalist development,” Dr. Berman wrote in the introduction to the Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition of Marx’s “Communist Manifesto,” published in 2011, “but he always believed the world horizon it created was a great human achievement, on which socialist and communist movements must build. Remember, the grand appeal to unite, with which the Manifesto ends, is addressed to the ‘workers of all countries.’ ”

Dr. Berman’s best-known book, “All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity,” was published in 1982 and took its name from a line in the Manifesto. Reviewing it in The New York Times, John Leonard called it “brilliant and exasperating.”

“Being modern is being new, whether we like it or not,” Mr. Leonard wrote, summarizing his assessment of Dr. Berman’s argument. “He likes it, Mr. Berman. Seize the day and change the world. Modernism is ‘a permanent revolution,’ full of radical sunrise and great dawn. We synthesize ourselves, without tears.”

Mr. Leonard added: “I’ve read Goethe, Marx, Baudelaire and Dostoyevsky, and I’ve been to Leningrad. Mr. Berman, generous and exuberant and dazzling, has been somewhere else, with a ‘shadow passport,’ inventing another history and literature, a romance of great ideas. I love this book and wish that I believed it.”

Marshall Howard Berman was born on Nov. 24, 1940, in the Bronx. His parents, Murray and Betty, ran a tag and label business in Times Square. His father died when his son was 14. Dr. Berman grew up taking the subway with his family to Times Square, a lifelong stimulant he celebrated in his 2006 book, “On the Town: One Hundred Years of Spectacle in Times Square.”

To Read the Rest

To Read All That Is Solid Melts Into the Air

More:

Marianna Reis: Marshall Berman, 1940-2013 (Verso)

Monday, September 16, 2013

Saturday, September 14, 2013

Law and Disorder Radio: Chris Hedges - Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt; Richard D. Wolff - Occupy the Economy: Challenging Capitalism, Pt. 2

Law and Disorder Radio

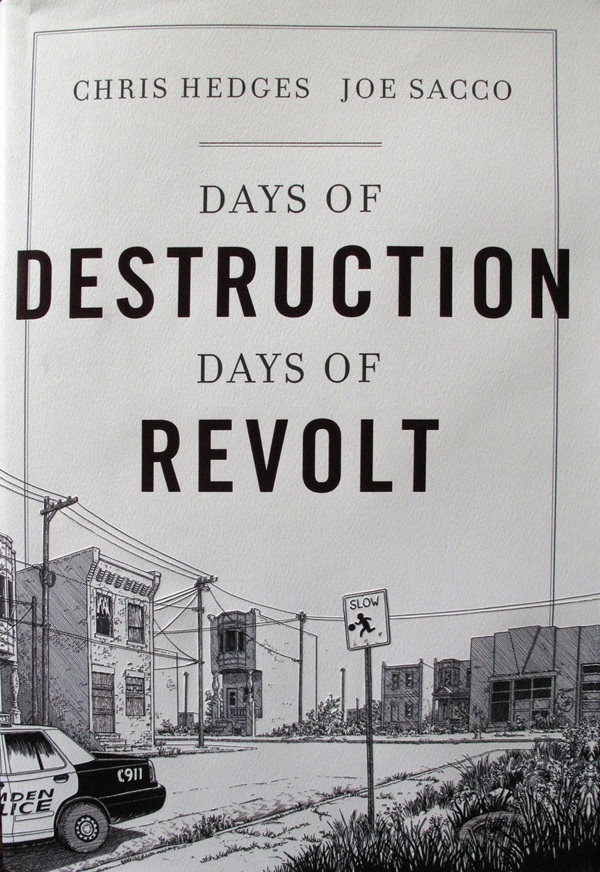

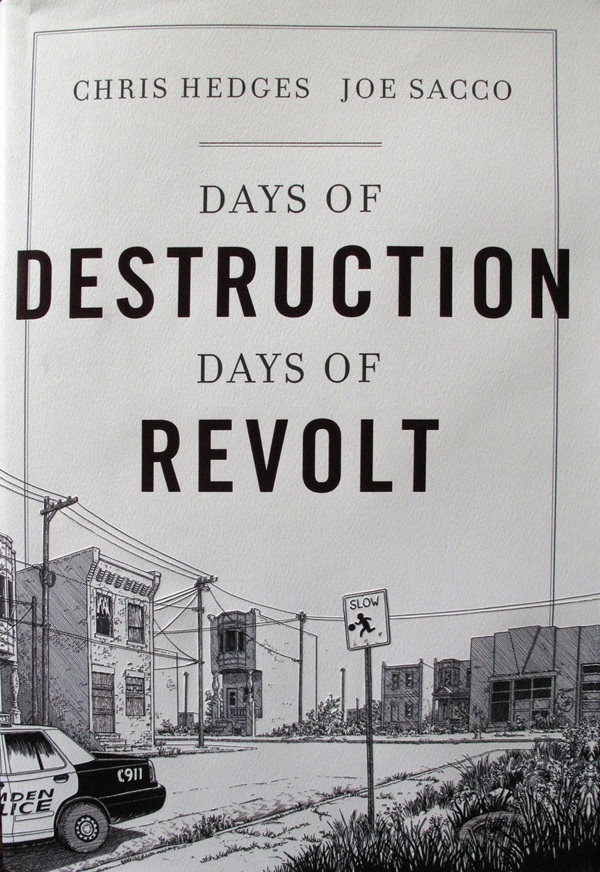

Days of Destruction Days of Revolt – Chris Hedges

We go now to an interview with Pulitzer-Prize winning author and journalist Chris Hedges. His latest book Days of Destruction Days of Revolt sends a powerful message about the perils of staying on the current destructive track in post capitalist America. The book is also filled with line drawing graphics, illustrating some of the most depraved areas in the United States. The book explores what Chris describes as the country’s sacrifice zones, areas that have been torn apart in the name of greed, progress and technological advancment. These areas include the streets of Camden New Jersey, the coal fields of West Virgina, the Lakota reservation of Pine Ridge in South Dakota.

Guest – Chris Hedges, Pulitzer-Prize winning author and journalist. He was also a war correspondent, specializing in American and Middle Eastern politics and societies. His most recent book is ‘Death of the Liberal Class (2010). Hedges is also known as the best-selling author of War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning (2002), which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction.

Occupy the Economy: Challenging Capitalism PART 2

Occupy the Economy: Challenging Capitalism is the title of Professor Rick Wolff’s new book. After more than a dozen interviews with Rick Wolff since 2008, the theme is consistent, beyond the corrupt banks and stock markets is a flawed economic system. A system that at worst needed to change direction in the 1970s when wages stopped increasing and the cost of living continued to rise. As we look around, the collapse has been coming down in steps, and many have been trying to dial back, save and prepare. This, as millions have lost their jobs, 401ks, pensions, and homes. Overseas, the waves of austerity continue to push through Europe as protests have erupted again in Spain.

Guest - Richard D. Wolff is Professor of Economics Emeritus, University of Massachusetts, Amherst where he taught economics from 1973 to 2008. He is currently a Visiting Professor in the Graduate Program in International Affairs of the New School University, New York City. He also teaches classes regularly at the Brecht Forum in Manhattan.

To Listen to the Episode

Days of Destruction Days of Revolt – Chris Hedges

We go now to an interview with Pulitzer-Prize winning author and journalist Chris Hedges. His latest book Days of Destruction Days of Revolt sends a powerful message about the perils of staying on the current destructive track in post capitalist America. The book is also filled with line drawing graphics, illustrating some of the most depraved areas in the United States. The book explores what Chris describes as the country’s sacrifice zones, areas that have been torn apart in the name of greed, progress and technological advancment. These areas include the streets of Camden New Jersey, the coal fields of West Virgina, the Lakota reservation of Pine Ridge in South Dakota.

Guest – Chris Hedges, Pulitzer-Prize winning author and journalist. He was also a war correspondent, specializing in American and Middle Eastern politics and societies. His most recent book is ‘Death of the Liberal Class (2010). Hedges is also known as the best-selling author of War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning (2002), which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction.

Occupy the Economy: Challenging Capitalism PART 2

Occupy the Economy: Challenging Capitalism is the title of Professor Rick Wolff’s new book. After more than a dozen interviews with Rick Wolff since 2008, the theme is consistent, beyond the corrupt banks and stock markets is a flawed economic system. A system that at worst needed to change direction in the 1970s when wages stopped increasing and the cost of living continued to rise. As we look around, the collapse has been coming down in steps, and many have been trying to dial back, save and prepare. This, as millions have lost their jobs, 401ks, pensions, and homes. Overseas, the waves of austerity continue to push through Europe as protests have erupted again in Spain.

Guest - Richard D. Wolff is Professor of Economics Emeritus, University of Massachusetts, Amherst where he taught economics from 1973 to 2008. He is currently a Visiting Professor in the Graduate Program in International Affairs of the New School University, New York City. He also teaches classes regularly at the Brecht Forum in Manhattan.

To Listen to the Episode

On Being: Her Deepness - Oceanographer Sylvia Earle

Her Deepness: Oceanographer Sylvia Earle

On Being

Sylvia Earle has done something no one else has — walked solo on the bottom of the sea, under a quarter mile of water. She tells what she saw — and what she has learned — about the giant, living system that is the ocean. And, she explains why seeing a shark is a sign for hope.

To Listen to the Episode

On Being

Sylvia Earle has done something no one else has — walked solo on the bottom of the sea, under a quarter mile of water. She tells what she saw — and what she has learned — about the giant, living system that is the ocean. And, she explains why seeing a shark is a sign for hope.

To Listen to the Episode

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Gina Apostol: Borges, Politics, and the Postcolonial

Borges, Politics, and the Postcolonial

by Gina Apostol

LA Review of Books

...

What is it about the writer in the First World that wants the Third World writer to be nakedly political, a blunt instrument bludgeoning his world’s ills? What is it about the critic that seems to wish upon the Third World the martyred activist who dies for a cause (O’Connell: “In his own country, six coups d’etat and three dictatorships” — one hears exclamation points of disappointment)? Where does this goddamned fantasy come from — that fantasy of the oppressed Third World artist who must risk his life to speak out, who’s not allowed to stay in bed and just read Kidnapped? I have to say, look at it this way: It only benefits dictatorships when all the Ken Saro-Wiwas die — and the loss of all the Ken Saro-Wiwas diminishes us all. Why is it not okay that an old man in Argentina lives for his art — and yet it is okay for a writer in The New Yorker whose country is targeting civilians abroad in precision assassinations to merely sit and write reviews about dead Argentines whose political feelings are insufficiently pronounced? Where is the great American artist leading his fellow citizens in barricades against the NSA? And why are these New Yorker critics not calling them out for their “refusal to engage with politics”?

Although it is amusing to imagine a blind librarian in Buenos Aires brandishing his weapons of Kipling tomes against the old junta, it is less possible to imagine Jonathan Franzen or Jeffrey Eugenides risking jail at all for any reason. Why are Americans allowed to be more cowardly than others?