[Compiling a list of

civil resistance,

social movement, and armed

resistance groups/organizations/movements post WWII -- please add your suggestions in the comments. Focus on groups/collectives, rather than individuals.)

1900-1994: The Pan-African Congress (International, met seven times)

1905-Ongoing: IWW: Industrial Workers of the World (International Union based in Chicago)

1917-1947: Gandhi and Civil Resistance in India

1922-1969: The Irish Republican Army

1930-1975: War and Revolution in Vietnam (Chronological mapping and terms from

Kevin Ruane's book -- for student, I have this book if you want to use it)

1942-1968: Congress of Racial Equality (USA: group continued past 1968, but it was no longer a civil resistance movement)

1969-1972: The Official Irish Republican Army

1969-1997: The Provisional Irish Republican Army

1945-1970: The US Civil Rights Movement

1945-Ongoing: The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists (USA)

1950-1960s: Mattachine Society (Based in Los Angeles, CA: one of the earliest American homosexual civil rights activist groups)

1950-Ongoing: Tibetan Resistance and Protests (Against Chinese Occupation)

1952-1955: Brown v. Board of Education (1954 US Supreme Court Decision)

1960-1969: Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (commonly referred to as SNCC, part of the Civil Rights Movement)

1960-1974: Students for a Democratic Society (USA)

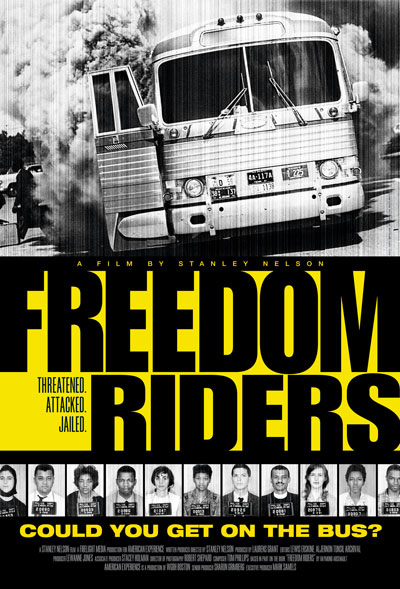

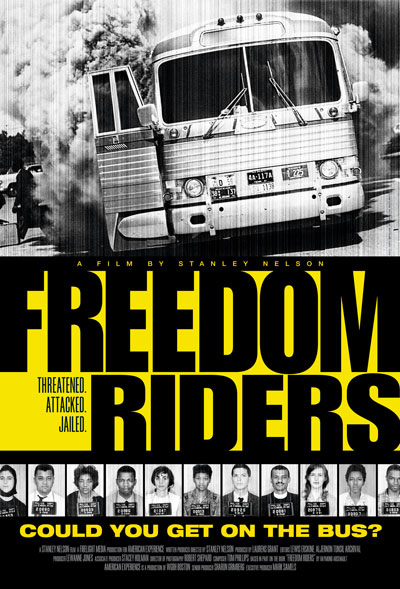

1961: Freedom Riders (Students from across the USA, joining to challenge Jim Crow policies in the South)

1962-Ongoing: Autonomism/Autonomia (Initially Italy, then Europe throughout 60s/70s, now international)

1962-ongoing: United Farm Workers (USA)

1963-1964: Freedom Schools (Mississippi)

1964-1965: Free Speech Movement (University of California, Berkeley, CA)

1964-1971: Occupation of Alcatraz (USA, by "Indians of All Tribes")

1966-1975: Black Power Movement (USA: many organizations, loosely associated)

1966-1982: Black Panther Party (USA)

1967-1972: Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (may include the Troubles that lasted until 1998 and the Provisional IRA campaign of 1969–1997)

1967-Ongoing: Vietnam Veterans Against the War (USA)

1968-Ongoing: American Indian Movement (Founded in Minneapolis, MN; active in the USA and Canada)

1968: May 1968 (Student led uprising in Paris)

1968: Mexican Student Movement of 1968 (also referred to as "Mexico 68")

1968: Prague Spring (Czechoslovakia)

1968: Worldwide Student and Worker Protests

1968-1970: Nader's Raiders (USA: student investigative committee that published "The Nader Report on the Federal Trade Commission")

1969: Stonewall Riots (Greenwich Village, New York City: Often cited as the beginning of the Gay Rights Movement)

1969-1977: Weather Underground (USA)

1969-Present: Union of Concerned Scientists (Founded by faculty an students at MIT -- now a national coalition of 400,000 people)

1970-1998: Red Army Faction (Also known as the Baader-Meinhoff Group: Germany)

1971-Ongoing: Greenpeace (Global Environmental Organization: founded in Vancouver, British Columbia and currently located in Amsterdam, Netherlands)

1971 - Ongoing: Public Citizen (Public Advocacy group: USA)

1974-1975: The Revolution of the Carnations (Portugal)

1975-Ongoing: Anti-Nuclear Movement (Global, many organizations)

1976-1983: Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Argentina)

1976-Ongoing: Animal Liberation Front

1976-Ongoing: National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty (USA: headquarters in Washington, DC)

1977-1979: The Iranian Revolution

1977-Ongoing: Sea Shepard Conservation Society (Based at Friday Harbor, WA and Melbourne, Victoria, Australia)

1978-1979: Iranian Revolution

1979-Ongoing: Earth First (Founded in Southwest USA, currently international)

1980: Gwangju Democratization Movement (also known as Gwangju Uprising: South Korea)

1980-1989: Solidarity (Polish Trade Union Movement)

1980-Ongoing: Food Not Bombs (International)

1980-Ongoing: Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights (Known as the National Labor Committee until 2011: based in Pittsburgh, PA)

1980-Ongoing: KRRS - Karnataka State Farmers Association (India)

1980-Ongoing: Landless Workers Movement (Brazil)

1980-Ongoing: PETA - People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Headquarters in Norfolk, VA)

1980-Ongoing: Plowshares (American Christian pacifist anti-nuclear organization that is now international in scope)

1981-2000: Greenham Commons Women's Peace Camp (Protesting Nuclear Weapons Site at Berkshire, England)

1983-1986: People Power Revolution (Philippines)

1983-1988: Political Mass Mobilization against Authoritarian Rule in Pinochet's Chile

1983-1994: Anti-Apartheid Movement (South Africa and Worldwide)

1984-1985: UK Miners' Strike (Coal Industry)

1984-Ongoing: Navdanya (India: non-governmental organization which promotes biodiversity conservation, biodiversity, organic farming, the rights of farmers, and the process of seed saving)

1986-1999: Operation Rescue (American anti-abortion protest organization)

1986-Ongoing: Critical Art Ensemble (USA tactical media/performance art collective

1986-0ngoing: Raging Grannies (Originated in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, also operating in the USA)

1987-Ongoing: Act Up (USA: Direct action advocacy group attempting to bring attention to the AIDS/HIV crisis)

1987-Ongoing: Palestinian Resistance Movement (Resisting occupation and settlement by the state of Israel: Various groups and two recognized "intifadas")

1988-Ongoing: Global Justice/Alter-Globalization (Global in scope and covering many social movements)

1989: Baltic Way/Baltic Chain Protest (Estonia/Latvia/Lithuania seeking to break off from the Soviet Union)

1989: Peaceful Revolution (East Germany and the Fall of the Berlin Wall)

1989: The Tianamen Square Protests (China)

1989: The Velvet Revolution (Czechoslovakia)

1989-1991: The Central/East European Revolutions and the Fall of the Soviet Union

1989-Ongoing: Adbusters Media Foundation (Founded in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; currently an international network of culture jammers)

1990-1998: Alabanian Civil Resistance in Kosovo

1990-Ongoing: Copwatch (Started in Berkeley, CA, later became a loose organization of groups across the USA and Europe)

1990-Ongoing: Electronic Frontier Foundation (Based in San Francisco, CA)

1990-Ongoing: School of the Americas Watch (USA)

1991-2000: Civil Society vs Slobodan Miloevic (Serbia/Federal Republic of Yugoslavia)

1991-Ongoing: The Green Party (USA)

1991-Ongoing: Reclaim the Streets (Started in UK, but since 1997 protests have appeared in other countries)

1992-Ongoing: Critical Mass (International, has led to mass arrests in New York City)

1992-Ongoing: Cypherpunks (International, centered around email lists)

1992-Ongoing: Earth Liberation Front (Founded in Brighton, UK. Now an International organization.)

1992-Ongoing: Mujeres Creando (Bolivia: Anarcha-Feminists)

1994-Ongoing: Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Mexico)

1995-Ongoing: National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (USA/Canada)

1996-1997: Protest Walks (Belgrade, Serbia)

1996-Ongoing: Crimethinc. Ex-Workers Collective (North America)

1996-Ongoing: The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights (Oakland, CA)

1996-Ongoing: Radical Cheerleaders (originated in USA, now international)

1999-Ongoing: Independent Media Center (Worldwide indy media centers -- founded during the 1999 WTO Protests in Seattle)

1999: WTO Protests in Seattle, WA (also known as the Battle in Seattle)

2000: Cochabamba Protests (Bolivian Water Wars)

2000-Ongoing: The Yes Men (Also RTMark Hacker collective: USA)

2001-Ongoing: A.N.S.W.E.R. (USA based anit-war and civil rights organization)

2001-Ongoing: Workers' Rights Consortium (USA)

2001-Ongoing: World Social Forum (Annual meeting of civil society organizations: headquarters in Porto Alegre, Brazil)

2002-2010: Iraq War Protests (Worldwide)

2002-Ongoing: Cope Pink (American anti-war women's organization)

2002-Ongoing: World Coalition Against the Death Penalty [Founded in Rome in 2002, headquarters in Strausborg, France]

2003: Rose Revolution (Georgia)

2003-Ongoing: Anonymous (Loosely associated hacker group -- worldwide)

2004-Ongoing: Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army (CIRCA: founded in UK, now global)

2004: Orange Revolution (Ukraine)

2004-Ongoing: Iraq Veterans Against the War (USA)

2005-Ongoing: Common Ground Collective (New Orleans, LA: decentralized network of non-profit organizations founded after Hurricane Katrina.)

2006-2007: Oaxaca Teachers Strike and Uprising (Mexico)

2006-Ongoing: Chilean Student Protests

2006-Ongoing: Wikileaks (International, online, not-for-profit organization publishing submissions of secret information, news leaks, and classified media from anonymous news sources and whistleblowers)

2007: Burmese Anti-Government Protests

2008: Republic Windows and Doors Strike (Goose Island, IL)

2009: Croatian Student Protests (University of Zagreb)

2009-2011: The Right to the City (Zagreb, Croatia)

2009-2012: Icelandic Financial Crisis Protests (Also known as Kitchenware Protests)

2009-Ongoing: Iranian Election Protests/Iranian Green Movement

2009-Ongoing: Tea Party Movement (USA)

2010-Ongoing: Appalachia Rising (USA: calling for abolition of mountaintop removal and surface mining)

2010-Ongoing: Arab Spring

2010-Ongoing: Greek Anti-Austerity Movement/Indignant Citizens Movement

2010-2011: Tunisian Revolution

2011-2012: Wisconsin Protests

2011-Ongoing: Anti-Austerity Protests (Global)

2011-Ongoing: Bahraini Uprising

2011-Ongoing: Egyptian Revolution

2011-Ongoing: Israeli Social Justice Protests

2011-Ongoing: Occupy Movement (Founded at Occupy Wall St, quickly became a worldwide movement)

2011-Ongoing: Spanish Indignados

2011-Ongoing: OUR Walmart (Based in Washington DC, National Organization)

2011-Ongoing: Yemeni Revolution

2012-Ongoing: International Organization for a Participatory Society

2012-Ongoing: Quebec Student Protests (Canada)

2012-Ongoing: Yo Soy 132 (Mexico: Student Protest Movement)