By J. Hoberman

Village Voice

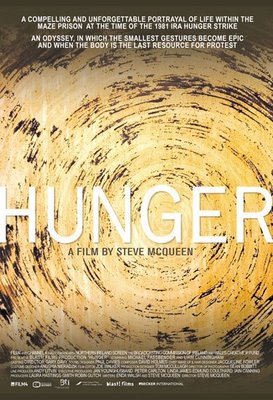

Hunger, too, is essentially contemplative. (It can be bracketed with such other "experiential," post-Gibson passions as The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, United 93, and Day Night Day Night.) The takes are long; the camera is mainly static, moving only to map out some confined space. The emphasis is on the individual setup. The piss-drenched corridor is scrubbed in real-time, with a guard working his way toward the viewer. The mode is materially Christian. The prisoners may use their Bibles for stationery or cigarette paper and exploit mass as a meeting place, but Sands (Michael Fassbender), who only appears midway through the movie, is an explicitly religious martyr. Even the Brits are into self-mortification—one cop compulsively washes his hands in scalding water. One of the few scenes outside the Maze is a cold-blooded execution, resulting in a savage pietà, the victim face-down in his mother's blood-spattered lap.

The heart of the movie is an extraordinary 20-minute conversation between Sands and a tough, far from unsympathetic parish priest (Liam Cunningham), much of it shot in a single take. Sands has requested a meeting to inform the priest of his planned hunger strike. The hardboiled banter (playwright Enda Walsh's main chance to riff out) is suffused in bleak Irish humor. All argument is stymied, however, by the prisoner's stubborn determination to fast unto death; the priest's irate "then fookin' life must mean nothin' to you" cues a close-up in which Sands answers with a story—or rather a long story within the story. It's not quite "The Grand Inquisitor," but I can't recall a movie with a more powerful priest-prisoner dialogue.

Hunger's harrowing final movement is informed not only by scripture, but by a thousand years of religious art—with Thatcher, or at least her voice, brought back to play Pontius Pilate. The subject is now exclusively Sands—or rather the physical state of his emaciated body—as he lies on a prison-hospital cot covered with running sores and stigmata lesions. One can barely watch this living cadaver or the bedside food tray that is his constant temptation. I've seen Hunger three times, and with each screening, the spectacle of violence, suffering, and pain becomes more awful and more awe-inspiring.

To Read the Entire Review

No comments:

Post a Comment