Cinema Scope

“Hey, do you wanna see somethin’?”—Driver in Drive

In the middle of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, a film punctuated by extreme flourishes of violence and vengeance, there is a period of peace. It occurs when Driver (Ryan Gosling), a quietly contained guy who holds down three jobs—auto mechanic, movie stunt driver, and getaway driver-for-hire—is asked by his auto-shop boss (Bryan Cranston) to drive home customer and Driver’s neighbour Irene (Carey Mulligan) and her little boy. En route, Driver takes a surprising detour from the street down to the concrete banks of the Los Angeles River, one of the city’s most iconic images, a grand public-works project born out of vast and tragic flooding the city endured generations ago. The river, choked into a narrow canal and surrounded by an elegantly paved canyon, has been used in too many movies and TV shows to possibly count, most recently by Bruce La Bruce for daytime sequences of L.A. Zombie (2010). Driver, true to character, uses it as a racetrack and as a bit of stunt track—mildly, as a kid’s in the car, and he’s a gentleman at heart—but also as a road to get somewhere.

The typical deployment of the Los Angeles River in cinema is as a symbol of dead ends, final stops, the place where the city dies, and people along with it. Not so for Refn, for whom Los Angeles is a new city, a place of discovery. Viewed from the majestic prospect of a high angle in long-shot widescreen, Driver stops at the place where the concrete river ends and gives way to the wild river, a startling image even for native Angelenos. He knows these kinds of places, having driven everywhere (so, in reality, does Gosling, who knows the city expertly and drove Refn around town as research, inspiration, and preparation). Refn understands those many places in Los Angeles that make it fairly unique, and reverses the usual clichéd knock on the place as one long paved sprawl. Constantly, the paved cityscape surrenders to the natural world, sidewalks dissolve into dirt trails, roads simply stop, buildings reach their limit when faced with cliffsides, massive chaparral, impregnable mountain ranges that cut through the metropolitan area. Driver leads mother and son to the wild river for a Tom Sawyer afternoon under the sun, a Southern California utopia—the ultimate getaway—an idyll that defines Drive and Driver in fundamental ways.

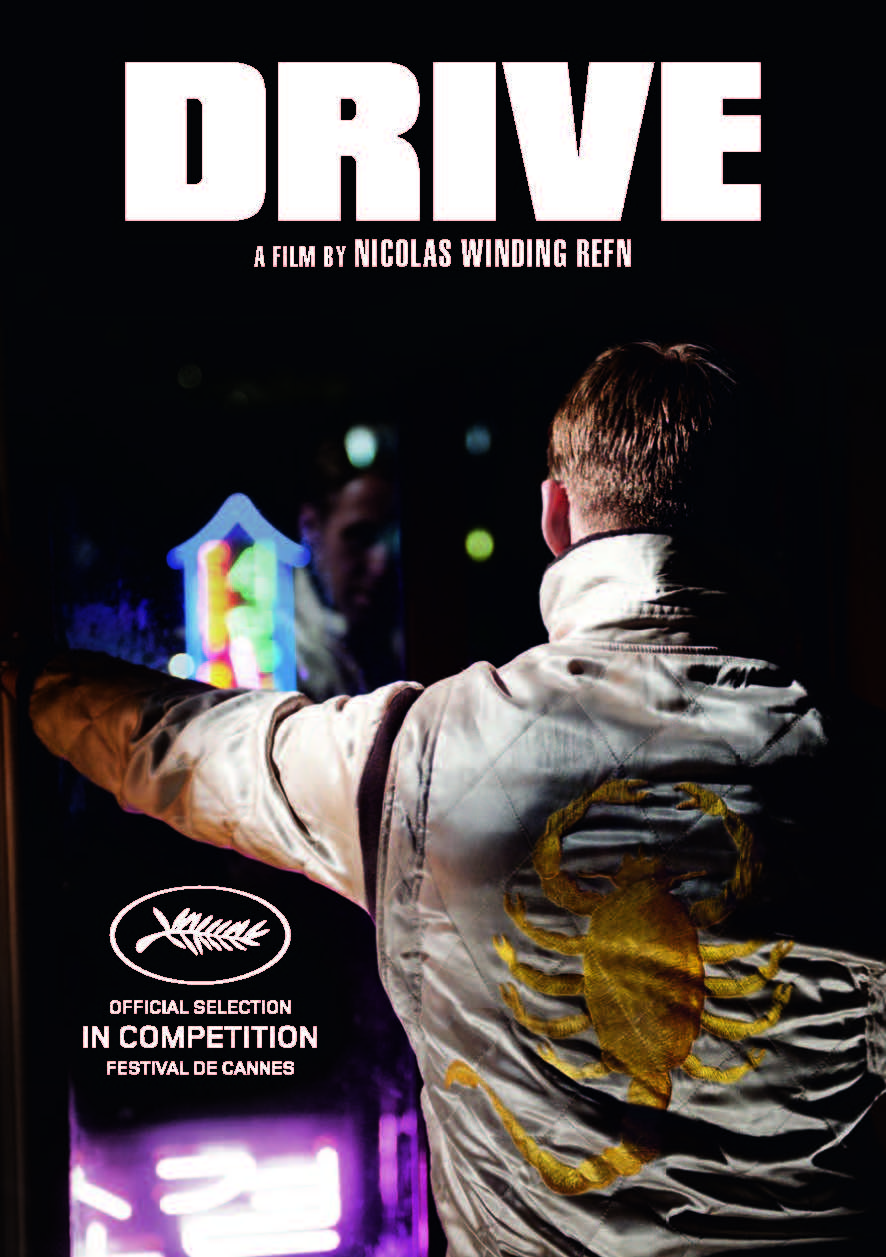

Superficially an action movie, Drive is actually a film in search of romance, zigzagging through an obstacle course of fairy tale and myth, and a hall of mirrors in which characters can be read as fantasy projections of others while being aware of themselves as figures inside a myth. Beloved in Cannes after days of disappointing films in the competition, Drive was perhaps welcomed by some for the wrong reason: as some kind of new read on Melville’s Le samourai (1967), with Gosling processing Alain Delon’s stoic killer. For once, the director has a sound interpretation that he’s willing to share with whomever cares to listen: Refn correctly argues that Drive’s foundation is in fairy tale, particularly its thematic of a character’s discovery of his own heroism, which Driver finds through the course of nurturing and protecting Irene, who’s made paradoxically more vulnerable when her convict husband returns home from prison. The necessary elimination of dragons—in the form of Albert Brooks’ ice-cold mobster Bernie Rose and Ron Perlman’s put-upon mobster Nino, to say nothing of a few nameless hitmen along the way—doesn’t so much make Driver into a killer, although he wreaks revenge with frighteningly intelligent brutality. Rather, it transforms him into a mythical figure who satisfies the imaginings of those around him, including Irene, who can nevertheless only marvel at him while knowing she can never have him. This is vastly different from Melville’s heightened existential world of professional killers who function by a code and live like lone wolves, apparently free of the need for genuine and reciprocal human contact. Delon’s Samourai is a corporeal killing machine; Gosling’s Driver is a young man in formation, whose work comprises (per his three jobs) repair, escape, and entertainment, and who finds his self during a gauntlet that perhaps only he can survive—an accidental knight who slays the beast.

This is a far stretch from James Sallis’ novel on which Hossein Amini’s screenplay is based, and, as Refn describes it, wildly different from Amini’s previous drafts written as a potential Universal franchise for Hugh Jackman. Sallis’ superb, laconic book, hardboiled to the core, as affectionate toward its city as it is cynical about the city’s most famous (show) business, could have been adapted pretty closely, even with its obsessive (and perhaps needless) jumps in chronology. But a knowledge of the book is helpful in appreciating the grand achievement in American cinema that Drive is. Hollywood has always been open to the invasive notions of outsiders, particularly European directors with strong points of view. Lubitsch, Lang, Boorman, Preminger, Wilder, von Sternberg, Herzog, Verhoeven, and von Stroheim all managed to import their native sensibilities with little compromise into the Hollywood system, and generally thrived intact. Refn’s ambition is clearly to make big movies for large audiences by his own sometimes-radical standards, which include mixing the hyper-violent ecstasies of the Pusher trilogy (1996, 2004, 2005), highly theatrical characters like Tom Hardy’s Bronson (2008), dreamlike dances of death as in Valhalla Rising (2009), and the romance of transformation in Drive. His new film is an act of will, pulling a fine but fairly standard piece of high-class pulp into something richer and more dynamic, modern in its self-consciousness as a work of art and entertainment, and Wellesian in its capacity to astonish, shock, and tease the mind’s perceptions. The fact that Refn is soon making a re-do of Logan’s Run with Gosling is a suggestion of a large-scaled cinema that’s aware of its kinetic powers, its artistic breadth, and its ability to kick it into the fifth gear.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment