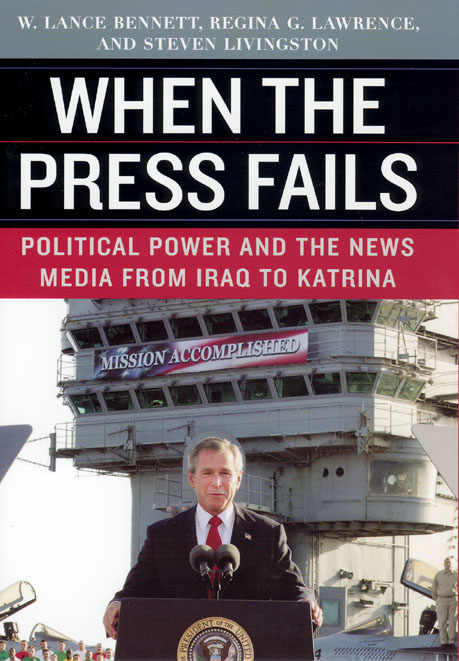

by W. Lance Bennett, Regina G. Lawrence, and Steven Livingston

University of California Press

Press Politics in America

The Case of the Iraq War

We now know that officials in the Bush administration built a case for the U.S. invasion of Iraq that was open to serious challenge. We also know that evidence disputing ongoing official claims about the war was often available to the mainstream press in a timely fashion. Yet the recurrent pattern, even years into the conflict, was for the official government line to trump evidence to the contrary in the news produced by mainstream news outlets reaching the preponderance of the people. Several years into the conflict, public opinion finally began to reflect the reality of a disintegrating Iraq heading toward civil war, with American troops caught in the middle. But that reckoning came several years too late to head off a disaster that historians may well deem far worse than Vietnam.

There is little doubt that reporting which challenges the public pronouncements of those in power is difficult when anything deviating from authorized versions of reality is met with intimidating charges of bias. Out of fairness, the press generally reports those charges, which in turn reverberate through the echo chambers of talk radio and pundit TV, with the ironic result that the media contribute to their own credibility problem. Yet it is precisely the lack of clear standards of press accountability (particularly guidelines for holding officials accountable) that opens the mainstream news to charges of bias from all sides. In short, the absence of much agreement on what the press should be doing makes it all the more difficult for news organizations to navigate an independent course through pressurized political situations.

The key question is, can the American press as it is currently constituted offer critical, independent reporting when democracy needs it most? In particular, this book examines whether the press capable of offering viewpoints independent of government spin at two key moments when democracy would most benefit: (1) when government’s own public-inquiry mechanisms fail to question potentially flawed or contentious policy initiatives, and (2) when credible sources outside government who might illuminate those policies are available to mainstream news organizations. It may seem obvious that the press should contest dubious policies under these circumstances, but our research indicates otherwise. The great irony of the U.S. press system is that it generally performs well—presenting competing views and vigorous debate—when government is already weighing competing initiatives in its various legal, legislative, or executive settings. Unfortunately, quite a different press often shows up when policy decisions of dubious wisdom go unchallenged within government arenas.

The Iraq Story as Told by the Unwritten Rules of Washington Journalism

Our story begins with the post-9/11 publicity given to the Bush administration’s claims that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction (the now infamous WMDs), and had connections to the terrorists who attacked the United States. Leading news organizations so emphasized those claims over available information to the contrary that two prestigious newspapers later issued apologies to their readers for having gotten so caught up in the inner workings of power in an administration determined to go to war that they lost focus on other voices and other views. Here are excerpts from a now legendary New York Times report from the editors to their readers:

We have found a number of instances of coverage that was not as rigorous as it should have been. In some cases, information that was controversial then, and seems questionable now, was insufficiently qualified or allowed to stand unchallenged. Looking back, we wish we had been more aggressive in re-examining the claims as new evidence emerged—or failed to emerge.

The problematic articles varied in authorship and subject matter, but many shared a common feature. They depended at least in part on information from a circle of Iraqi informants, defectors and exiles bent on “regime change” in Iraq, people whose credibility has come under increasing public debate in recent weeks. … Complicating matters for journalists, the accounts of these exiles were often eagerly confirmed by United States officials convinced of the need to intervene in Iraq. …

Some critics of our coverage during that time have focused blame on individual reporters. Our examination, however, indicates that the problem was more complicated. Editors at several levels who should have been challenging reporters and pressing for more skepticism were perhaps too intent on rushing scoops into the paper. … Articles based on dire claims about Iraq tended to get prominent display, while follow-up articles that called the original ones into question were sometimes buried. In some cases, there was no follow-up at all.

Despite this introspection, much the same pattern of deferring to officials and underreporting available challenges to their claims would soon repeat itself—beginning the very month in which this critical self-assessment appeared—in reporting on the treatment of prisoners in U.S. military detention centers in Iraq and elsewhere. The importance of the Abu Ghraib story for understanding the close dependence of the press on government spin is developed more fully in chapter 3. For now, the point is that this pattern of calibrating political reality in the news to the inner circles of Washington power will go on, despite occasional moments of self-examination by the press, unless leading news organizations and the journalism profession somehow resolve (and develop a standard) to temper their preoccupation with the powerful officials whose communication experts often manage them so well.

To Read the Rest of the Excerpt