by Stephen Maher

Monthly Review

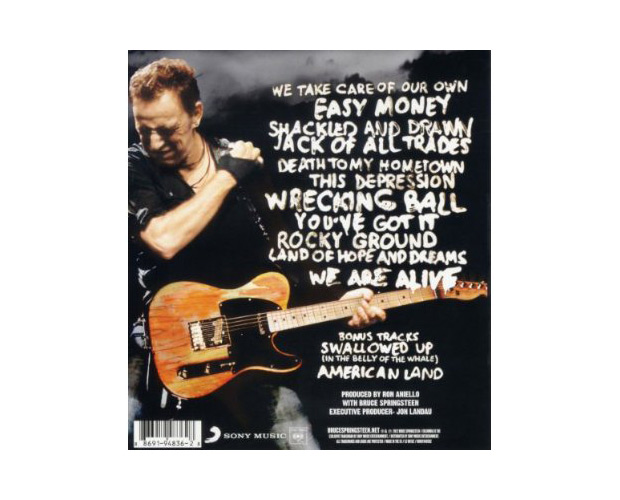

On his most recent album, Wrecking Ball, Bruce Springsteen crafted a powerful statement of support for the working class, the existence of which barely penetrates contemporary art or politics. This is not an accident: the growing power of capital over public discourse has provided it a forceful means through which to shape individual consciousness, and establish an apolitical and at most technocratic understanding of power. Those at the top, we are led to believe, are there because of their technical skills and have risen by meritocratic means—the vast gulfs created by inequalities in wealth, power, and privilege are ignored. In fact, gigantic corporations—controlled by the 1% (or by the 0.1%)—dominate all forms of production. Even in the cultural realm, the art and voices of the working class are sidelined and squelched. Working people thus become invisible. As Occupy has helped make clear, the 99%, though divided in all kinds of ways, share the collective disappointment of being ruledby others, as opposed to ruling themselves;of constantly producing and reproducing the bases of wealth and power at the top of society, rather than fulfilling their own developmental potential…. Power over surplus distribution—and thus nearly everything else—is left to an unelected ownership class. The overwhelming majority of the population is unable to locate itself in the “democratic consensus” or the dominant culture.

In our ad-driven consumer age, it is a monumental struggle to encourage sympathy and solidarity by bringing the stories and views of working people to a mass audience. Indeed, one of the greatest successes of the Occupy movement has been to force the idea into the national discourse that the working class exists as such (we are the 99%), a notion that is usually reserved for the radical fringe. On Wrecking Ball, Springsteen channels and supports the proletarian discourse of the 99%, which overcomes post-political, technocratic ideology and constructs a world sharply divided between exploited and exploiters. He crosses over from his earlier lament for a fallen America and the unfulfilled promise of the American dream to rage at the “robber barons” who “ate the flesh off everything they’ve found” and “whose crimes have gone unpunished,” calling on workers to stand united in seeking social justice. In telling the seldom-heard stories of working people and subjectivizing them as victims of the violence of capital, Wrecking Ball represents an important salvo in the cultural struggle, providing justification for and encouraging solidarity with the cause of the 99%.

In its review of the album, the popular music website Pitchfork chides Springsteen for “rail[ing] against those up on ‘Banker’s Hill’ in the sort of black-and-white terms that continue to plague and cleave his home country.” In suggesting that those who have united as “the 99%” are merely troublemakers, and that Occupy is actually a “plague” on society, Pitchfork—regarded as a hip and liberal publication in the hegemonic discourse—paradoxically adopts a position that would make Newt Gingrich blush. How is this possible? In fact, the Pitchfork review can be taken as a model to demonstrate the shortcomings of the so-called “hipster” current. This social current, of which Pitchfork is the ultimate expression, is the embodiment of postmodern skepticism and relativism. Artistically, it is concerned solely with exhibiting middle-class angst, while it presents liberation as the styling of an individualized consumerism and pornographic self-expression. Any transformational social project, or genuine contact with the working class, is seen as anachronistic and totalitarian. As Arcade Fire described on their 2010 album The Suburbs, what appears as progressive experimentation and “liberation” is really Rococo—trivial but elaborate ornamentation that amounts to little more than an indication of privilege and isolation, like the elaborate dress of the court of Louis XVI.

Naturally, this ideology—which emphasizes consumerism and the liberation of the market while discouraging social and political engagement—poses no threat whatsoever to structures of power and domination, and is therefore ubiquitous. It has served to mask and even defend the marginalization of working-class art while concealing the domination of the cultural terrain by the forces of capital, under the guise of liberation and freedom. As Arcade Fireput it, “they seem wild, but they are so tame.” With Wrecking Ball, Springsteen has produced a record of startling beauty, that unambiguously proclaims solidarity with the 99% and reaffirms the possibility of a better world. It is a powerful statement in support of the Occupiers’ struggle against a ruling class that is waging unmitigated war against workers and the poor. The force of this statement, and the nature of Pitchfork’s response, help to reveal the class bias concealed behind postmodern “common sense” and hipster skepticism.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment