Hard Times Inspire Ky. College Students To Action

by Noah Adams

NPR

NPR's Hard Times series features stories of economic hardship and also stories of hope. We asked for ideas from listeners, and Emily Nugent of Berea College in Kentucky responded, writing: "With a student body composed entirely of students from low socio-economic backgrounds, Berea students know about the challenges Americans are facing." Noah Adams went in search of Emily and the Berea College story.

This school was started six years before the Civil War. It was to be both integrated and coeducational. And the poor students became part of the mission. The small college town, Berea, is right at the edge of the Bluegrass region. There's a rise of mountains to the east. It's where Appalachia begins.

By 1931, University of Chicago President Robert Hutchins was able to say Berea was in a "different class."

"It does what no other college can do; what it does must be done," he said.

This year, the Washington Monthly ranking of 100 liberal arts colleges has Berea at No. 1.

The school has 1,600 students, most of them from southern Appalachia, but there's someone here from every state. And at Berea, their tuition is free — all four years are paid for through the college's $931 million endowment. It might be the only way these students could go to college. On average, they come from families with household incomes of about $25,000.

Emily Nugent, a sophomore at Berea, is a political science major from Lapeer, Mich. She recalls coming with her mother for her first visit to the campus.

"I finished my tour, and my mom turned to me and said, 'If you choose this school or any school, I want you to be as proud of what you're doing as these students seem to be. I don't care what school you choose, but this is the only one I've seen where people seem to love what they're doing,' " Nugent remembers.

Choi, a senior majoring in Spanish and political science from Bergen County, N.J., came to this country from South Korea. After four years at Berea, he graduates next month. Soon he'll go to San Francisco and walk across America to call attention to the plight of immigrants.

"Especially in these hard times, I feel that people are placing blame on the other people who look a little different from everyone else. I've lived in this country for more than half my life, and I'm still undocumented," Choi says. "I feel that Berea has empowered me to go back to my own community, which is the immigrant community, and try to find ways I can fill my role in."

In October, about 40 Berea students rode a bus to New York City for the Occupy Wall Street rallies. Senior Kurstin Jones, from Cincinnati, was with them.

To Read the Rest of the Story or Listen to it in its entirety

"My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel--it is, above all, to make you see." -- Joseph Conrad (1897)

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Rebecca Solnit: You Can Crush the Flowers, But You Can’t Stop the Spring

You Can Crush the Flowers, But You Can’t Stop the Spring

By Rebecca Solnit

ZNET

Last Tuesday, I awoke in lower Manhattan to the whirring of helicopters overhead, a war-zone sound that persisted all day and then started up again that Thursday morning, the two-month anniversary of Occupy Wall Street and a big day of demonstrations in New York City. It was one of the dozens of ways you could tell that the authorities take Occupy Wall Street seriously, even if they profoundly mistake what kind of danger it poses. If you ever doubted whether you were powerful or you mattered, just look at the reaction to people like you (or your children) camped out in parks from Oakland to Portland, Tucson to Manhattan.

Of course, “camped out” doesn’t quite catch the spirit of the moment, because those campsites are the way people have come together to bear witness to their hopes and fears, to begin to gather their power and discuss what is possible in our disturbingly unhinged world, to make clear how wrong our economic system is, how corrupt the powers that support it are, and to begin the search for a better way. Consider it an irony that the campsites are partly for sleeping, but symbols of the way we have awoken.

When civil society sleeps, we’re just a bunch of individuals absorbed in our private lives. When we awaken, on campgrounds or elsewhere, when we come together in public and find our power, the authorities are terrified. They often reveal their ugly side, their penchant for violence and for hypocrisy.

Consider the liberal mayor of Oakland, who speaks with outrage of people camping without a permit but has nothing to say about the police she dispatched to tear-gas a woman in a wheelchair, shoot a young Iraq war veteran in the head, and assault people while they slept. Consider the billionaire mayor of New York who dispatched the NYPD on a similar middle-of-the-night raid on November 15th. Recall this item included in a bald list of events that night: “tear-gassing the kitchen tent.” Ask yourself when did kitchens really need to be attacked with chemical weapons?

Does an 84-year-old woman need to be tear-gassed in Seattle? Does a three-tours-of-duty veteran need to be beaten until his spleen ruptures in Oakland? Does our former poet laureate need to be bashed in the ribs after his poet wife is thrown to the ground at UC Berkeley? Admittedly, this is a system that regards people as disposable, but not usually so literally.

Two months ago, the latest protests against that system began. The response only confirms our vision of how it all works. They are fighting fire with gasoline. Perhaps being frightened makes them foolish. After all, once civil society rouses itself from slumber, it can be all but unstoppable. (If they were smart they’d try to soothe it back to sleep.) “Arrest one of us; two more appear. You can’t arrest an idea!” said the sign held by a man in a Guy Fawkes mask in reoccupied Zuccotti Park last Thursday.

Last Wednesday in San Francisco, 100 activists occupied the Bank of America, even erecting a symbolic tent inside it in which a dozen activists immediately took refuge. At the Berkeley campus of the University of California, setting up tents on any grounds was forbidden, so the brilliant young occupiers used clusters of helium balloons to float tents overhead, a smart image of defiance and sky-high ambition. And the valiant UC Davis students, after several of them were pepper-sprayed in the face while sitting peacefully on the ground, evicted the police, chanting, “You can go! You can go!” They went.

Occupy Oakland has been busted up three times and still it thrives. To say nothing of the other 1,600 occupations in the growing movement.

Alexander Dubcek, the government official turned hero of the Prague Spring uprising of 1968, once said, “You can crush the flowers, but you can’t stop the spring.”

The busting of Zuccotti Park and the effervescent, ingenious demonstrations elsewhere are a reminder that, despite the literal “occupations” on which this protean movement has been built, it can soar as high as those Berkeley balloons and take many unexpected forms. Another OWS sign, “The beginning is near,” caught the mood of the moment. Flowers seem like the right image for this uprising led by the young, those who have been most crushed by the new economic order, and who bloom by rebelling and rebel by blooming.

The Best and the Worst

Now world-famous Zuccotti Park is just a small concrete and brown marble-paved scrap of land surrounded by tall buildings. Despite the “Occupy Wall Street” label, it’s actually two blocks north of that iconic place. It’s rarely noted that the park is within sight of, and kitty-corner to, Ground Zero, where the World Trade Center towers crumbled.

What was born and what died that day a decade ago has everything to do with what’s going on in and around the park, the country, and the world now. For this, al-Qaeda is remarkably irrelevant, except as the outfit that long ago triggered an incident that instantly released both the best and the worst in our society.

The best was civil society. As I wandered in the Zuccotti Park area last week, I was struck again by how much what really happened on the morning of September 11th has been willfully misremembered. It can be found nowhere in the plaques and monuments. Firemen more than deserve their commemorations, but mostly they acted in vain, on bad orders from above, and with fatally flawed communications equipment. The fact is: the people in the towers and the neighborhood -- think of them as civil society coming together in crisis -- largely rescued themselves, and some of them told the firefighters to head down, not up.

We need memorials to the coworkers who carried their paraplegic accountant colleague down 69 flights of stairs while in peril themselves; to Ada Rosario-Dolch, the principal who got all of the High School for Leadership, a block away, safely evacuated, while knowing her sister had probably been killed in one of those towers; to the female executives who walked the blind newspaper seller to safety in Greenwich Village; to the unarmed passengers of United Flight 93, who were the only ones to combat terrorism effectively that day; and to countless, nameless others. We need monuments to ourselves, to civil society.

Ordinary people shone that morning. They were not terrorized; they were galvanized into action, and they were heroic. And it didn’t stop with that morning either. That day, that week they began to talk about what the events of 9/11 actually meant for them, and they acted to put their world back together, practically and philosophically. All of which terrified the Bush administration, which soon launched not only its “global war on terror” and its invasion of Afghanistan, but a campaign against civil society. It was aimed at convincing each of us that we should stay home, go shopping, fear everything except the government, and spy on each other.

The only monument civil society ever gets is itself, and the satisfaction of continuing to do the work that matters, the work that has no bosses and no paychecks, the work of connecting, caring, understanding, exploring, and transforming. So much about Occupy Wall Street resonates with what came in that brief moment a decade before and then was shut down for years.

That little park that became “occupied” territory brought to mind the way New York’s Union Square became a great public forum in the weeks after 9/11, where everyone could gather to mourn, connect, discuss, debate, bear witness, share food, donate or raise money, write on banners, and simply live in public. (Until the city shut that beautiful forum down in the name of sanitation -- that sacred cow which by now must be mating with the Wall Street Bull somewhere in the vicinity of Zuccotti Park.)

It was remarkable how many New Yorkers lived in public in those weeks after 9/11. Numerous people have since told me nostalgically of how the normal boundaries came down, how everyone made eye contact, how almost anyone could talk to almost anyone else. Zuccotti Park and the other Occupies I’ve visited -- Oakland, San Francisco, Tucson, New Orleans -- have been like that, too. You can talk to strangers. In fact, it’s almost impossible not to, so much do people want to talk, to tell their stories, to hear yours, to discuss our mutual plight and what solutions to it might look like.

It’s as though the great New York-centric moment of openness after 9/11, when we were ready to reexamine our basic assumptions and look each other in the eye, has returned, and this time it’s not confined to New York City, and we’re not ready to let anyone shut it down with rubbish about patriotism and peril, safety and sanitation.

It’s as if the best of the spirit of the Obama presidential campaign of 2008 was back -- without the foolish belief that one man could do it all for civil society. In other words, this is a revolt, among other things, against the confinement of decision-making to a thoroughly corrupted and corporate-money-laced electoral sphere and against the pitfalls of leaders. And it represents the return in a new form of the best of the post-9/11 moment.

As for the worst after 9/11 -- you already know the worst. You’ve lived it. The worst was two treasury-draining wars that helped cave in the American dream, a loss of civil liberties, privacy, and governmental accountability. The worst was the rise of a national security state to almost unimaginable proportions, a rogue state that is our own government, and that doesn’t hesitate to violate with impunity the Geneva Convention, the Bill of Rights, and anything else it cares to trash in the name of American "safety" and "security." The worst was blind fealty to an administration that finished off making this into a country that serves the 1% at the expense, or even the survival, of significant parts of the 99%. More recently, it has returned as another kind of worst: police brutality (speaking of blind fealty to the 1%).

To Read the Rest of the Essay

By Rebecca Solnit

ZNET

Last Tuesday, I awoke in lower Manhattan to the whirring of helicopters overhead, a war-zone sound that persisted all day and then started up again that Thursday morning, the two-month anniversary of Occupy Wall Street and a big day of demonstrations in New York City. It was one of the dozens of ways you could tell that the authorities take Occupy Wall Street seriously, even if they profoundly mistake what kind of danger it poses. If you ever doubted whether you were powerful or you mattered, just look at the reaction to people like you (or your children) camped out in parks from Oakland to Portland, Tucson to Manhattan.

Of course, “camped out” doesn’t quite catch the spirit of the moment, because those campsites are the way people have come together to bear witness to their hopes and fears, to begin to gather their power and discuss what is possible in our disturbingly unhinged world, to make clear how wrong our economic system is, how corrupt the powers that support it are, and to begin the search for a better way. Consider it an irony that the campsites are partly for sleeping, but symbols of the way we have awoken.

When civil society sleeps, we’re just a bunch of individuals absorbed in our private lives. When we awaken, on campgrounds or elsewhere, when we come together in public and find our power, the authorities are terrified. They often reveal their ugly side, their penchant for violence and for hypocrisy.

Consider the liberal mayor of Oakland, who speaks with outrage of people camping without a permit but has nothing to say about the police she dispatched to tear-gas a woman in a wheelchair, shoot a young Iraq war veteran in the head, and assault people while they slept. Consider the billionaire mayor of New York who dispatched the NYPD on a similar middle-of-the-night raid on November 15th. Recall this item included in a bald list of events that night: “tear-gassing the kitchen tent.” Ask yourself when did kitchens really need to be attacked with chemical weapons?

Does an 84-year-old woman need to be tear-gassed in Seattle? Does a three-tours-of-duty veteran need to be beaten until his spleen ruptures in Oakland? Does our former poet laureate need to be bashed in the ribs after his poet wife is thrown to the ground at UC Berkeley? Admittedly, this is a system that regards people as disposable, but not usually so literally.

Two months ago, the latest protests against that system began. The response only confirms our vision of how it all works. They are fighting fire with gasoline. Perhaps being frightened makes them foolish. After all, once civil society rouses itself from slumber, it can be all but unstoppable. (If they were smart they’d try to soothe it back to sleep.) “Arrest one of us; two more appear. You can’t arrest an idea!” said the sign held by a man in a Guy Fawkes mask in reoccupied Zuccotti Park last Thursday.

Last Wednesday in San Francisco, 100 activists occupied the Bank of America, even erecting a symbolic tent inside it in which a dozen activists immediately took refuge. At the Berkeley campus of the University of California, setting up tents on any grounds was forbidden, so the brilliant young occupiers used clusters of helium balloons to float tents overhead, a smart image of defiance and sky-high ambition. And the valiant UC Davis students, after several of them were pepper-sprayed in the face while sitting peacefully on the ground, evicted the police, chanting, “You can go! You can go!” They went.

Occupy Oakland has been busted up three times and still it thrives. To say nothing of the other 1,600 occupations in the growing movement.

Alexander Dubcek, the government official turned hero of the Prague Spring uprising of 1968, once said, “You can crush the flowers, but you can’t stop the spring.”

The busting of Zuccotti Park and the effervescent, ingenious demonstrations elsewhere are a reminder that, despite the literal “occupations” on which this protean movement has been built, it can soar as high as those Berkeley balloons and take many unexpected forms. Another OWS sign, “The beginning is near,” caught the mood of the moment. Flowers seem like the right image for this uprising led by the young, those who have been most crushed by the new economic order, and who bloom by rebelling and rebel by blooming.

The Best and the Worst

Now world-famous Zuccotti Park is just a small concrete and brown marble-paved scrap of land surrounded by tall buildings. Despite the “Occupy Wall Street” label, it’s actually two blocks north of that iconic place. It’s rarely noted that the park is within sight of, and kitty-corner to, Ground Zero, where the World Trade Center towers crumbled.

What was born and what died that day a decade ago has everything to do with what’s going on in and around the park, the country, and the world now. For this, al-Qaeda is remarkably irrelevant, except as the outfit that long ago triggered an incident that instantly released both the best and the worst in our society.

The best was civil society. As I wandered in the Zuccotti Park area last week, I was struck again by how much what really happened on the morning of September 11th has been willfully misremembered. It can be found nowhere in the plaques and monuments. Firemen more than deserve their commemorations, but mostly they acted in vain, on bad orders from above, and with fatally flawed communications equipment. The fact is: the people in the towers and the neighborhood -- think of them as civil society coming together in crisis -- largely rescued themselves, and some of them told the firefighters to head down, not up.

We need memorials to the coworkers who carried their paraplegic accountant colleague down 69 flights of stairs while in peril themselves; to Ada Rosario-Dolch, the principal who got all of the High School for Leadership, a block away, safely evacuated, while knowing her sister had probably been killed in one of those towers; to the female executives who walked the blind newspaper seller to safety in Greenwich Village; to the unarmed passengers of United Flight 93, who were the only ones to combat terrorism effectively that day; and to countless, nameless others. We need monuments to ourselves, to civil society.

Ordinary people shone that morning. They were not terrorized; they were galvanized into action, and they were heroic. And it didn’t stop with that morning either. That day, that week they began to talk about what the events of 9/11 actually meant for them, and they acted to put their world back together, practically and philosophically. All of which terrified the Bush administration, which soon launched not only its “global war on terror” and its invasion of Afghanistan, but a campaign against civil society. It was aimed at convincing each of us that we should stay home, go shopping, fear everything except the government, and spy on each other.

The only monument civil society ever gets is itself, and the satisfaction of continuing to do the work that matters, the work that has no bosses and no paychecks, the work of connecting, caring, understanding, exploring, and transforming. So much about Occupy Wall Street resonates with what came in that brief moment a decade before and then was shut down for years.

That little park that became “occupied” territory brought to mind the way New York’s Union Square became a great public forum in the weeks after 9/11, where everyone could gather to mourn, connect, discuss, debate, bear witness, share food, donate or raise money, write on banners, and simply live in public. (Until the city shut that beautiful forum down in the name of sanitation -- that sacred cow which by now must be mating with the Wall Street Bull somewhere in the vicinity of Zuccotti Park.)

It was remarkable how many New Yorkers lived in public in those weeks after 9/11. Numerous people have since told me nostalgically of how the normal boundaries came down, how everyone made eye contact, how almost anyone could talk to almost anyone else. Zuccotti Park and the other Occupies I’ve visited -- Oakland, San Francisco, Tucson, New Orleans -- have been like that, too. You can talk to strangers. In fact, it’s almost impossible not to, so much do people want to talk, to tell their stories, to hear yours, to discuss our mutual plight and what solutions to it might look like.

It’s as though the great New York-centric moment of openness after 9/11, when we were ready to reexamine our basic assumptions and look each other in the eye, has returned, and this time it’s not confined to New York City, and we’re not ready to let anyone shut it down with rubbish about patriotism and peril, safety and sanitation.

It’s as if the best of the spirit of the Obama presidential campaign of 2008 was back -- without the foolish belief that one man could do it all for civil society. In other words, this is a revolt, among other things, against the confinement of decision-making to a thoroughly corrupted and corporate-money-laced electoral sphere and against the pitfalls of leaders. And it represents the return in a new form of the best of the post-9/11 moment.

As for the worst after 9/11 -- you already know the worst. You’ve lived it. The worst was two treasury-draining wars that helped cave in the American dream, a loss of civil liberties, privacy, and governmental accountability. The worst was the rise of a national security state to almost unimaginable proportions, a rogue state that is our own government, and that doesn’t hesitate to violate with impunity the Geneva Convention, the Bill of Rights, and anything else it cares to trash in the name of American "safety" and "security." The worst was blind fealty to an administration that finished off making this into a country that serves the 1% at the expense, or even the survival, of significant parts of the 99%. More recently, it has returned as another kind of worst: police brutality (speaking of blind fealty to the 1%).

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Monday, November 28, 2011

William Scott: The People's Library of Occupy Wall Street Lives On

The People's Library of Occupy Wall Street Lives On

by William Scott

The Nation

The People’s Library at Zuccotti Park—a collection of more than 5,000 donated books of every genre and subject, all free for the taking—was created not only to serve the Occupy Wall Street protesters; it was meant to provide knowledge and reading pleasure for the wider public as well, including residents of Lower Manhattan. It was also a library to the world at large, since many visitors to the park stopped by the library to browse our collection, to donate books of their own and to take books for themselves.

At about 2:30 am on November 15, the People’s Library was destroyed by the NYPD, acting on the authority of Mayor Michael Bloomberg. With no advance notice, an army of police in riot gear raided the park, seized everything in it and threw it all into garbage trucks and dumpsters. Despite Mayor Bloomberg’s Twitter promise that the library was safely stored and could be retrieved, only about 1,100 books were recovered, and some of those are in unreadable condition. Four library laptops were also destroyed, as well as all the bookshelves, storage bins, stamps and cataloging supplies and the large tent that housed the library.

For the past six weeks I have been living and working as a librarian in the People’s Library, camping out on the ground next to it. I’m an English professor at the University of Pittsburgh, and I’ve chosen to spend my sabbatical at Occupy Wall Street to participate in the movement and to build and maintain the collection of books at the People’s Library. I love books—reading them, writing in them, arranging them, holding them, even smelling them. I also love having access to books for free. I love libraries and everything they represent. To see an entire collection of donated books, including many titles I would have liked to read, thoughtlessly ransacked and destroyed by the forces of law and order was one of the most disturbing experiences of my life. My students in Pittsburgh struggle to afford to buy the books they need for their courses. Our extensive collection of scholarly books and journals alone would have sufficed to provide reading materials for dozens of college classrooms. With public libraries around the country fighting to survive in the face of budget cuts, layoffs and closings, the People’s Library has served as a model of what a public library can be: operated for the people and by the people.

During the raid, Stephen Boyer, a poet, friend and OWS librarian, read poems from the Occupy Wall Street Poetry Anthology (see peopleslibrary.wordpress.com [1]) aloud directly into the faces of riot police. As they pushed us away from the park with shields, fists, billy clubs and tear gas, I stood next to Stephen and watched while he yelled poetry at the top of his lungs into the oncoming army of riot police. Then, something incredible happened. Several of the police leaned in closer to hear the poetry. They lifted their helmet shields slightly to catch the words Stephen was shouting out to them, even while their fellow cops continued to stampede us. The next day, an officer who was guarding the entrance to Zuccotti Park told Stephen how touched he was by the poetry, how moved he was to see that we cared enough about words and books that we would risk violent treatment and arrest just to defend our love of books and the wisdom they contain.

At 6 pm on November 15, a group of writers and supporters of the People’s Library appeared at the reopened park carrying books, and within minutes we received around 200 donations. All night and into the next day folks stopped by to donate to and take from the collection. Because the new rules of the park forbid us from lying down or leaving anything there, Stephen and I stayed up all night to protect the books until other librarians came to take over for us. Frustrated and exhausted, but still exhilarated and eager to maintain the momentum of the movement, we kept the People’s Library open all day in the pouring rain, storing books in Ziploc baggies to keep them dry.

Then at 7:30 pm on November 16, the People’s Library was again raided and thrown in the trash—this time by a combination of police and Brookfield Properties’ sanitation team. The NYPD first barricaded the library by lining up in front of it, forming an impenetrable wall of cops. An officer then announced through a bullhorn that we should come and collect our books, or they would be confiscated and removed. Seconds later, they began dumping books into trash bins that they had wheeled into the park for that purpose. As they were throwing out the books, a fellow OWS librarian asked one of the NYPD patrolmen why they were doing this. His answer: “I don’t know.”

Five minutes after it started, the raid was over and the People’s Library’s collection was once again sitting in a pile of garbage. Yet just as the trash bins were being carted off, a man stepped out of the crowd with a book in his hand to donate to us: Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem. We joyously accepted and cataloged it, placing it on display under a new sign for the library that we made right then on a blank sheet of paper. A true people’s library, after all, doesn’t depend on any particular number of books, since it’s ultimately about the way those books are collected and lent out to the public.

We’re still accepting donations and lending books just as we always have, but we’ve reorganized ourselves somewhat. We now have three mobile units staffed by OWS librarians, which we can take anywhere we want. For the November 17 Day of Action, we made sure the People’s Library was there to supply books to anyone who wanted them. All day long, OWS librarians walked among the crowds shouting, “The People’s Library 3.0, mobile and in the streets!” For me, it was easily the most rewarding day in the six weeks I’ve been with the movement. The people we met at our mobile units—Occupiers from New York and other states, friends of the People’s Library, tourists—went out of their way to express their joy that we were still here. They also struggled to articulate their feelings of loss, frustration, anger, disgust and outrage over the seizure and destruction of the library. All we could say in response was, “We’re here to stay! Please take a book! They belong to you!” A group of eight OWS librarians even started a new chant: “Whose books? Your books!” It quickly caught fire with the other marchers.

To Read the Rest of the Article

by William Scott

The Nation

The People’s Library at Zuccotti Park—a collection of more than 5,000 donated books of every genre and subject, all free for the taking—was created not only to serve the Occupy Wall Street protesters; it was meant to provide knowledge and reading pleasure for the wider public as well, including residents of Lower Manhattan. It was also a library to the world at large, since many visitors to the park stopped by the library to browse our collection, to donate books of their own and to take books for themselves.

At about 2:30 am on November 15, the People’s Library was destroyed by the NYPD, acting on the authority of Mayor Michael Bloomberg. With no advance notice, an army of police in riot gear raided the park, seized everything in it and threw it all into garbage trucks and dumpsters. Despite Mayor Bloomberg’s Twitter promise that the library was safely stored and could be retrieved, only about 1,100 books were recovered, and some of those are in unreadable condition. Four library laptops were also destroyed, as well as all the bookshelves, storage bins, stamps and cataloging supplies and the large tent that housed the library.

For the past six weeks I have been living and working as a librarian in the People’s Library, camping out on the ground next to it. I’m an English professor at the University of Pittsburgh, and I’ve chosen to spend my sabbatical at Occupy Wall Street to participate in the movement and to build and maintain the collection of books at the People’s Library. I love books—reading them, writing in them, arranging them, holding them, even smelling them. I also love having access to books for free. I love libraries and everything they represent. To see an entire collection of donated books, including many titles I would have liked to read, thoughtlessly ransacked and destroyed by the forces of law and order was one of the most disturbing experiences of my life. My students in Pittsburgh struggle to afford to buy the books they need for their courses. Our extensive collection of scholarly books and journals alone would have sufficed to provide reading materials for dozens of college classrooms. With public libraries around the country fighting to survive in the face of budget cuts, layoffs and closings, the People’s Library has served as a model of what a public library can be: operated for the people and by the people.

During the raid, Stephen Boyer, a poet, friend and OWS librarian, read poems from the Occupy Wall Street Poetry Anthology (see peopleslibrary.wordpress.com [1]) aloud directly into the faces of riot police. As they pushed us away from the park with shields, fists, billy clubs and tear gas, I stood next to Stephen and watched while he yelled poetry at the top of his lungs into the oncoming army of riot police. Then, something incredible happened. Several of the police leaned in closer to hear the poetry. They lifted their helmet shields slightly to catch the words Stephen was shouting out to them, even while their fellow cops continued to stampede us. The next day, an officer who was guarding the entrance to Zuccotti Park told Stephen how touched he was by the poetry, how moved he was to see that we cared enough about words and books that we would risk violent treatment and arrest just to defend our love of books and the wisdom they contain.

At 6 pm on November 15, a group of writers and supporters of the People’s Library appeared at the reopened park carrying books, and within minutes we received around 200 donations. All night and into the next day folks stopped by to donate to and take from the collection. Because the new rules of the park forbid us from lying down or leaving anything there, Stephen and I stayed up all night to protect the books until other librarians came to take over for us. Frustrated and exhausted, but still exhilarated and eager to maintain the momentum of the movement, we kept the People’s Library open all day in the pouring rain, storing books in Ziploc baggies to keep them dry.

Then at 7:30 pm on November 16, the People’s Library was again raided and thrown in the trash—this time by a combination of police and Brookfield Properties’ sanitation team. The NYPD first barricaded the library by lining up in front of it, forming an impenetrable wall of cops. An officer then announced through a bullhorn that we should come and collect our books, or they would be confiscated and removed. Seconds later, they began dumping books into trash bins that they had wheeled into the park for that purpose. As they were throwing out the books, a fellow OWS librarian asked one of the NYPD patrolmen why they were doing this. His answer: “I don’t know.”

Five minutes after it started, the raid was over and the People’s Library’s collection was once again sitting in a pile of garbage. Yet just as the trash bins were being carted off, a man stepped out of the crowd with a book in his hand to donate to us: Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem. We joyously accepted and cataloged it, placing it on display under a new sign for the library that we made right then on a blank sheet of paper. A true people’s library, after all, doesn’t depend on any particular number of books, since it’s ultimately about the way those books are collected and lent out to the public.

We’re still accepting donations and lending books just as we always have, but we’ve reorganized ourselves somewhat. We now have three mobile units staffed by OWS librarians, which we can take anywhere we want. For the November 17 Day of Action, we made sure the People’s Library was there to supply books to anyone who wanted them. All day long, OWS librarians walked among the crowds shouting, “The People’s Library 3.0, mobile and in the streets!” For me, it was easily the most rewarding day in the six weeks I’ve been with the movement. The people we met at our mobile units—Occupiers from New York and other states, friends of the People’s Library, tourists—went out of their way to express their joy that we were still here. They also struggled to articulate their feelings of loss, frustration, anger, disgust and outrage over the seizure and destruction of the library. All we could say in response was, “We’re here to stay! Please take a book! They belong to you!” A group of eight OWS librarians even started a new chant: “Whose books? Your books!” It quickly caught fire with the other marchers.

To Read the Rest of the Article

Mark Ames: How UC Davis Chancellor Linda Katehi Brought Oppression Back To Greece's Universities

[via Danny Mayer]

How UC Davis Chancellor Linda Katehi Brought Oppression Back To Greece's Universities

by Mark Ames

The Smirking Chimp

A friend of mine sent me this link [1] claiming that UC Davis chancellor “Chemical” Linda Katehi, whose crackdown on peaceful university students shocked America, played a role in allowing Greece security forces to raid university campuses for the first time since the junta was overthrown in 1974. (H/T: Crooked Timber [2]) I’ve checked this out with our friend in Athens, reporter Kostas Kallergis (who runs the local blog “When The Crisis Hits The Fan” [3]), and he confirmed it–Linda Katehi really is the worst of all possible chancellors imaginable, the worst for us, and the worst for her native Greece.

First, some background: Last week, The eXiled published two pieces on Greece’s doomed struggle against global financial institutions—an article [4] on how the EU and Western bankers essentially overthrew [5] the nearly-uppity government of prime minister George Papandreou, and replaced it with a banker-friendly “technocratic” government that includes real-life, no-bullshit neo-Nazis and fascists [6] from the LAOS party, fascists with a banker-friendly fetish for imposing austerity measures. One of those fascists, Makis “Hammer” Voridis [7], spent his early 20s “hammering” non-fascist students for sport. Voridis was booted out of Athens University law school after ax-bashing fellow law students who didn’t share his fascist ideology. Today, Mikaes Voridis is the Minister for Infrastructure in the “technocratic” government. Imagine Lt. John Pike [8] in leather and an 80s hairdo, carrying a homemade ax rather than a pepper spray weapon, and you have Makis “Hammer” Voridis.

We also published a powerful and necessary history primer [9]by Greek journalist Kostas Kallergis [10] on the almost-holy significance of the date November 17 [11] in contemporary Greek history. On that day in 1973, pro-democracy students at the Athens Polytechnic university were crushed by tanks and soldiers sent in by the ruling junta dictatorship, which collapsed less than a year later, returning democracy to Greece. With CIA backing, the generals in the junta overthrew Greece’s democracy in 1967, jailed and tortured suspected leftists (meaning students and union leaders), and even went the extra-weird-fascist mile by banning the Beatles, mini-skirts, long hair, along with Mark Twain and Sophocles. The student rebellion at the Polytechnic, and its martyrdom, became the symbol for Greeks of their fight against fascism and tyranny, something like the briefcase man at Tiananmen Square, or the slaughtered rebels of the Boston Tea Party. That is why, as soon as the junta was overthrown and democracy restored in 1974, Greece immediately banned the presence of army, police or state security forces on university campuses. This so-called “university asylum” law turned Greece’s university campuses into cop-free zones of “political asylum,” where no one could interfere in the students’ rights to dissent against the government.

Today, thanks in part to UC Davis chancellor “Chemical” Linda Katehi, Greek university campuses are no longer protected from state security forces [12]. She helped undo her native country’s “university asylum” laws just in time for the latest austerity measures to kick in. Incredibly, Katehi attacked university campus freedom despite the fact that she was once a student at the very center of Greece’s anti-junta, pro-democracy rebellion–although what she was doing there, if anything at all, no one really knows.

Here’s the sordid back-story: Linda Katehi was born in Athens in 1954 and got her undergraduate degree at the famous Athens Polytechnic. She just happened to be the right age to be a student at the Polytechnic university on the very day, November 17, 1973, when the junta sent in tanks and soldiers to crush her fellow pro-democracy students. It was only after democracy was restored in 1974–and Greek university campuses were turned into police-free “asylum zones”–that Linda Katehi eventually moved to the USA, earning her PhD at UCLA.

Earlier this year, Linda Katehi served on an “International Committee On Higher Education In Greece,” along with a handful of American, European and Asian academics. The ostensible goal was to “reform” Greece’s university system. The real problem, from the real powers behind the scenes (banksters and the EU), was how to get Greece under control as the austerity-screws tightened. It didn’t take a genius to figure out that squeezing more money from Greece’s beleaguered citizens would mean clamping down on Greece’s democracy and doing something about those pesky Greek university students. And that meant taking away the universities’ “amnesty” protection, in place for nearly four decades, so that no one, nowhere, would be safe from police truncheons, gas, or bullets.

Thanks to the EU, bankers, and UC Davis chancellor Linda Katehi, university freedom for Greece’s students has taken a huge, dark step backwards.

Here you can read a translation [13]of the report co-authored by UC Davis’ Linda Katehi [14]–the report which brought about the end of Greece’s “university asylum” law.What’s particularly disturbing is that Linda Katehi was the only Greek on that commission. Presumably that would give her a certain amount of extra sway–both because of her inside knowledge, and because of her moral authority among the other non-Greek committee members. And yet, Linda Katehi signed off on a report that provided the rationale for repealing Greece’s long-standing “university asylum” law. She basically helped undo the very heart and soul of Greece’s pro-democracy uprising against the junta.

And perfect timing too, now that one of Greece’s most notorious pro-junta fascists is a member of the new austerity government.

To Read the Rest of the Commentary and to Access Extensive Hyperlinked Resources

How UC Davis Chancellor Linda Katehi Brought Oppression Back To Greece's Universities

by Mark Ames

The Smirking Chimp

A friend of mine sent me this link [1] claiming that UC Davis chancellor “Chemical” Linda Katehi, whose crackdown on peaceful university students shocked America, played a role in allowing Greece security forces to raid university campuses for the first time since the junta was overthrown in 1974. (H/T: Crooked Timber [2]) I’ve checked this out with our friend in Athens, reporter Kostas Kallergis (who runs the local blog “When The Crisis Hits The Fan” [3]), and he confirmed it–Linda Katehi really is the worst of all possible chancellors imaginable, the worst for us, and the worst for her native Greece.

First, some background: Last week, The eXiled published two pieces on Greece’s doomed struggle against global financial institutions—an article [4] on how the EU and Western bankers essentially overthrew [5] the nearly-uppity government of prime minister George Papandreou, and replaced it with a banker-friendly “technocratic” government that includes real-life, no-bullshit neo-Nazis and fascists [6] from the LAOS party, fascists with a banker-friendly fetish for imposing austerity measures. One of those fascists, Makis “Hammer” Voridis [7], spent his early 20s “hammering” non-fascist students for sport. Voridis was booted out of Athens University law school after ax-bashing fellow law students who didn’t share his fascist ideology. Today, Mikaes Voridis is the Minister for Infrastructure in the “technocratic” government. Imagine Lt. John Pike [8] in leather and an 80s hairdo, carrying a homemade ax rather than a pepper spray weapon, and you have Makis “Hammer” Voridis.

We also published a powerful and necessary history primer [9]by Greek journalist Kostas Kallergis [10] on the almost-holy significance of the date November 17 [11] in contemporary Greek history. On that day in 1973, pro-democracy students at the Athens Polytechnic university were crushed by tanks and soldiers sent in by the ruling junta dictatorship, which collapsed less than a year later, returning democracy to Greece. With CIA backing, the generals in the junta overthrew Greece’s democracy in 1967, jailed and tortured suspected leftists (meaning students and union leaders), and even went the extra-weird-fascist mile by banning the Beatles, mini-skirts, long hair, along with Mark Twain and Sophocles. The student rebellion at the Polytechnic, and its martyrdom, became the symbol for Greeks of their fight against fascism and tyranny, something like the briefcase man at Tiananmen Square, or the slaughtered rebels of the Boston Tea Party. That is why, as soon as the junta was overthrown and democracy restored in 1974, Greece immediately banned the presence of army, police or state security forces on university campuses. This so-called “university asylum” law turned Greece’s university campuses into cop-free zones of “political asylum,” where no one could interfere in the students’ rights to dissent against the government.

Today, thanks in part to UC Davis chancellor “Chemical” Linda Katehi, Greek university campuses are no longer protected from state security forces [12]. She helped undo her native country’s “university asylum” laws just in time for the latest austerity measures to kick in. Incredibly, Katehi attacked university campus freedom despite the fact that she was once a student at the very center of Greece’s anti-junta, pro-democracy rebellion–although what she was doing there, if anything at all, no one really knows.

Here’s the sordid back-story: Linda Katehi was born in Athens in 1954 and got her undergraduate degree at the famous Athens Polytechnic. She just happened to be the right age to be a student at the Polytechnic university on the very day, November 17, 1973, when the junta sent in tanks and soldiers to crush her fellow pro-democracy students. It was only after democracy was restored in 1974–and Greek university campuses were turned into police-free “asylum zones”–that Linda Katehi eventually moved to the USA, earning her PhD at UCLA.

Earlier this year, Linda Katehi served on an “International Committee On Higher Education In Greece,” along with a handful of American, European and Asian academics. The ostensible goal was to “reform” Greece’s university system. The real problem, from the real powers behind the scenes (banksters and the EU), was how to get Greece under control as the austerity-screws tightened. It didn’t take a genius to figure out that squeezing more money from Greece’s beleaguered citizens would mean clamping down on Greece’s democracy and doing something about those pesky Greek university students. And that meant taking away the universities’ “amnesty” protection, in place for nearly four decades, so that no one, nowhere, would be safe from police truncheons, gas, or bullets.

Thanks to the EU, bankers, and UC Davis chancellor Linda Katehi, university freedom for Greece’s students has taken a huge, dark step backwards.

Here you can read a translation [13]of the report co-authored by UC Davis’ Linda Katehi [14]–the report which brought about the end of Greece’s “university asylum” law.What’s particularly disturbing is that Linda Katehi was the only Greek on that commission. Presumably that would give her a certain amount of extra sway–both because of her inside knowledge, and because of her moral authority among the other non-Greek committee members. And yet, Linda Katehi signed off on a report that provided the rationale for repealing Greece’s long-standing “university asylum” law. She basically helped undo the very heart and soul of Greece’s pro-democracy uprising against the junta.

And perfect timing too, now that one of Greece’s most notorious pro-junta fascists is a member of the new austerity government.

To Read the Rest of the Commentary and to Access Extensive Hyperlinked Resources

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Michael Sicinski: Port of Forgotten Dreams -- Aki Kaurismäki’s Le Havre (Finland, 2011)

Port of Forgotten Dreams: Aki Kaurismäki’s Le Havre

by Michael Sicinski

Cinema Scope

Can there be such a thing as a productive political fantasy? This is far from a rhetorical question, and as I revisit Aki Kaurismäki’s latest film, which is without a doubt a political film for our times, I find myself grappling with this very question. This is because the idea of what constitutes “political representation” shifted, I believe, since Kaurismäki began making films in his proletarian-modernist style—a fact of which the Finnish master is very much aware. I actually suspect that the terms of the political, and what it means to represent it, locate it, assign it agency, have quite possibly changed in a significant way, from the moment in May when Le Havre had its world premiere at Cannes, and now, six months later, as it enters commercial release. To put it another way: does Kaurismäki’s fantastical optimism appear hopelessly naïve as the Occupy movement trudges on, in the face of tear gas and rubber bullets? What exactly would a properly activist film even look like right now? To begin to answer this question, and assess Kaurismäki’s place within any tentative web of solutions, we must work backwards, to understand what Le Havre is and where it comes from.

In a certain sense, there has been, at best, a pluralistic exploration, and at worst a crisis, in the very concept of “political cinema” since the general decay of the various international New Wave cinemas of the 1960s and ‘70s. D. N. Rodowick referred to this as “the crisis of political modernism” (typified, in some senses, by Straub-Huillet, Oshima, and mid-period Godard), the increasing uncertainty that stringent form and radical content would necessarily serve to mutually reinforce one another, or more to the point, that a sturdy recipe for cinematic radicalism, regardless of social or historical context, had been achieved. In a manner of speaking, the “last man standing” from this wreckage was Fassbinder, who, by channeling his leftism through Sirkian affect, found a way forward, even when certain of the far-left pieties that the political modernists held dear were undermined, if temporarily, by terrorist excess. The ur-text for this crisis of conscience is undoubtedly Fassbinder’s contribution to the 1978 omnibus Germany in Autumn, in which the news of German special forces storming the hijacked Lufthansa flight in Mogadishu induced panic in the filmmaker that all individuals with leftist ties would soon be rounded up indiscriminately. Meanwhile, his elderly mother prattles on about the need for a new, benevolent Führer.

If there is one dominant spirit presiding over Kaurismäki’s work it’s probably Fassbinder, although it’s not always readily apparent. Aki’s love for rockabilly, film noir, and the rebel streak in classic Hollywood (Nick Ray, Sam Fuller) makes him a much more obvious kinsman of Wim Wenders. But what Kaurismäki has consistently drawn from Fassbinder, in terms of a refined formalist politic, is a way of organizing and specularizing space, of rendering power visible on the interpersonal and the “street” level—that zone that Michel de Certeau designates as the place of small “tactics” rather than grand “strategies.” Kaurismäki’s shots frame characters and their environments with a highly sophisticated simplicity, pinning them down within a geographically defined “social gest” but at the same time delineating a persistently palpable three dimensions around them. What’s more, in his editing schemes, Aki continues this delineated space as socially defined, as a network of looks and gazes, of suspicions, solicitations and entreaties. His still frames verge on portraiture, but it is always a mode of depiction activated by the social contract.

To Read the Rest of the Response

by Michael Sicinski

Cinema Scope

Can there be such a thing as a productive political fantasy? This is far from a rhetorical question, and as I revisit Aki Kaurismäki’s latest film, which is without a doubt a political film for our times, I find myself grappling with this very question. This is because the idea of what constitutes “political representation” shifted, I believe, since Kaurismäki began making films in his proletarian-modernist style—a fact of which the Finnish master is very much aware. I actually suspect that the terms of the political, and what it means to represent it, locate it, assign it agency, have quite possibly changed in a significant way, from the moment in May when Le Havre had its world premiere at Cannes, and now, six months later, as it enters commercial release. To put it another way: does Kaurismäki’s fantastical optimism appear hopelessly naïve as the Occupy movement trudges on, in the face of tear gas and rubber bullets? What exactly would a properly activist film even look like right now? To begin to answer this question, and assess Kaurismäki’s place within any tentative web of solutions, we must work backwards, to understand what Le Havre is and where it comes from.

In a certain sense, there has been, at best, a pluralistic exploration, and at worst a crisis, in the very concept of “political cinema” since the general decay of the various international New Wave cinemas of the 1960s and ‘70s. D. N. Rodowick referred to this as “the crisis of political modernism” (typified, in some senses, by Straub-Huillet, Oshima, and mid-period Godard), the increasing uncertainty that stringent form and radical content would necessarily serve to mutually reinforce one another, or more to the point, that a sturdy recipe for cinematic radicalism, regardless of social or historical context, had been achieved. In a manner of speaking, the “last man standing” from this wreckage was Fassbinder, who, by channeling his leftism through Sirkian affect, found a way forward, even when certain of the far-left pieties that the political modernists held dear were undermined, if temporarily, by terrorist excess. The ur-text for this crisis of conscience is undoubtedly Fassbinder’s contribution to the 1978 omnibus Germany in Autumn, in which the news of German special forces storming the hijacked Lufthansa flight in Mogadishu induced panic in the filmmaker that all individuals with leftist ties would soon be rounded up indiscriminately. Meanwhile, his elderly mother prattles on about the need for a new, benevolent Führer.

If there is one dominant spirit presiding over Kaurismäki’s work it’s probably Fassbinder, although it’s not always readily apparent. Aki’s love for rockabilly, film noir, and the rebel streak in classic Hollywood (Nick Ray, Sam Fuller) makes him a much more obvious kinsman of Wim Wenders. But what Kaurismäki has consistently drawn from Fassbinder, in terms of a refined formalist politic, is a way of organizing and specularizing space, of rendering power visible on the interpersonal and the “street” level—that zone that Michel de Certeau designates as the place of small “tactics” rather than grand “strategies.” Kaurismäki’s shots frame characters and their environments with a highly sophisticated simplicity, pinning them down within a geographically defined “social gest” but at the same time delineating a persistently palpable three dimensions around them. What’s more, in his editing schemes, Aki continues this delineated space as socially defined, as a network of looks and gazes, of suspicions, solicitations and entreaties. His still frames verge on portraiture, but it is always a mode of depiction activated by the social contract.

To Read the Rest of the Response

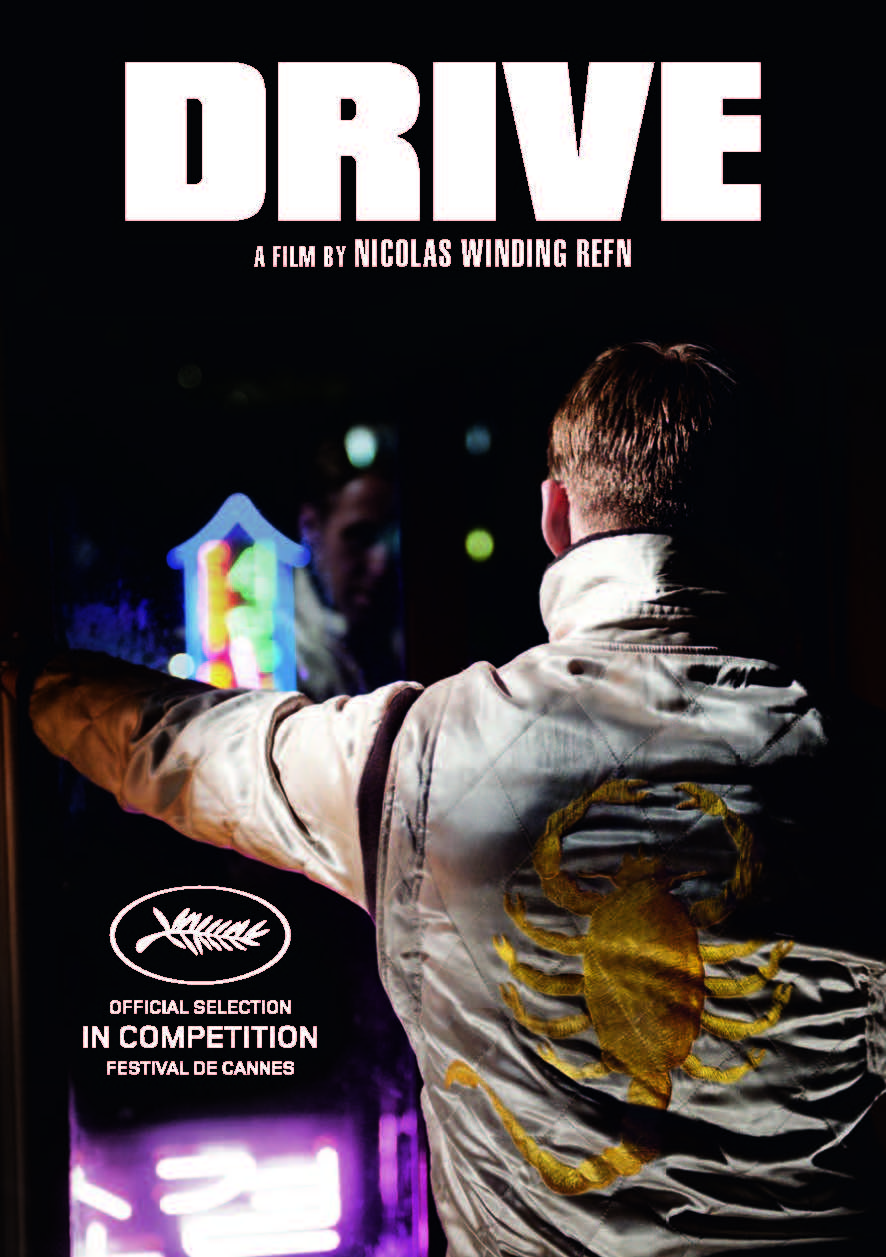

Cinema Scope: Nicolas Winding Refn and the Search for a Real Hero

Nicolas Winding Refn and the Search for a Real Hero

Cinema Scope

“Hey, do you wanna see somethin’?”—Driver in Drive

In the middle of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, a film punctuated by extreme flourishes of violence and vengeance, there is a period of peace. It occurs when Driver (Ryan Gosling), a quietly contained guy who holds down three jobs—auto mechanic, movie stunt driver, and getaway driver-for-hire—is asked by his auto-shop boss (Bryan Cranston) to drive home customer and Driver’s neighbour Irene (Carey Mulligan) and her little boy. En route, Driver takes a surprising detour from the street down to the concrete banks of the Los Angeles River, one of the city’s most iconic images, a grand public-works project born out of vast and tragic flooding the city endured generations ago. The river, choked into a narrow canal and surrounded by an elegantly paved canyon, has been used in too many movies and TV shows to possibly count, most recently by Bruce La Bruce for daytime sequences of L.A. Zombie (2010). Driver, true to character, uses it as a racetrack and as a bit of stunt track—mildly, as a kid’s in the car, and he’s a gentleman at heart—but also as a road to get somewhere.

The typical deployment of the Los Angeles River in cinema is as a symbol of dead ends, final stops, the place where the city dies, and people along with it. Not so for Refn, for whom Los Angeles is a new city, a place of discovery. Viewed from the majestic prospect of a high angle in long-shot widescreen, Driver stops at the place where the concrete river ends and gives way to the wild river, a startling image even for native Angelenos. He knows these kinds of places, having driven everywhere (so, in reality, does Gosling, who knows the city expertly and drove Refn around town as research, inspiration, and preparation). Refn understands those many places in Los Angeles that make it fairly unique, and reverses the usual clichéd knock on the place as one long paved sprawl. Constantly, the paved cityscape surrenders to the natural world, sidewalks dissolve into dirt trails, roads simply stop, buildings reach their limit when faced with cliffsides, massive chaparral, impregnable mountain ranges that cut through the metropolitan area. Driver leads mother and son to the wild river for a Tom Sawyer afternoon under the sun, a Southern California utopia—the ultimate getaway—an idyll that defines Drive and Driver in fundamental ways.

Superficially an action movie, Drive is actually a film in search of romance, zigzagging through an obstacle course of fairy tale and myth, and a hall of mirrors in which characters can be read as fantasy projections of others while being aware of themselves as figures inside a myth. Beloved in Cannes after days of disappointing films in the competition, Drive was perhaps welcomed by some for the wrong reason: as some kind of new read on Melville’s Le samourai (1967), with Gosling processing Alain Delon’s stoic killer. For once, the director has a sound interpretation that he’s willing to share with whomever cares to listen: Refn correctly argues that Drive’s foundation is in fairy tale, particularly its thematic of a character’s discovery of his own heroism, which Driver finds through the course of nurturing and protecting Irene, who’s made paradoxically more vulnerable when her convict husband returns home from prison. The necessary elimination of dragons—in the form of Albert Brooks’ ice-cold mobster Bernie Rose and Ron Perlman’s put-upon mobster Nino, to say nothing of a few nameless hitmen along the way—doesn’t so much make Driver into a killer, although he wreaks revenge with frighteningly intelligent brutality. Rather, it transforms him into a mythical figure who satisfies the imaginings of those around him, including Irene, who can nevertheless only marvel at him while knowing she can never have him. This is vastly different from Melville’s heightened existential world of professional killers who function by a code and live like lone wolves, apparently free of the need for genuine and reciprocal human contact. Delon’s Samourai is a corporeal killing machine; Gosling’s Driver is a young man in formation, whose work comprises (per his three jobs) repair, escape, and entertainment, and who finds his self during a gauntlet that perhaps only he can survive—an accidental knight who slays the beast.

This is a far stretch from James Sallis’ novel on which Hossein Amini’s screenplay is based, and, as Refn describes it, wildly different from Amini’s previous drafts written as a potential Universal franchise for Hugh Jackman. Sallis’ superb, laconic book, hardboiled to the core, as affectionate toward its city as it is cynical about the city’s most famous (show) business, could have been adapted pretty closely, even with its obsessive (and perhaps needless) jumps in chronology. But a knowledge of the book is helpful in appreciating the grand achievement in American cinema that Drive is. Hollywood has always been open to the invasive notions of outsiders, particularly European directors with strong points of view. Lubitsch, Lang, Boorman, Preminger, Wilder, von Sternberg, Herzog, Verhoeven, and von Stroheim all managed to import their native sensibilities with little compromise into the Hollywood system, and generally thrived intact. Refn’s ambition is clearly to make big movies for large audiences by his own sometimes-radical standards, which include mixing the hyper-violent ecstasies of the Pusher trilogy (1996, 2004, 2005), highly theatrical characters like Tom Hardy’s Bronson (2008), dreamlike dances of death as in Valhalla Rising (2009), and the romance of transformation in Drive. His new film is an act of will, pulling a fine but fairly standard piece of high-class pulp into something richer and more dynamic, modern in its self-consciousness as a work of art and entertainment, and Wellesian in its capacity to astonish, shock, and tease the mind’s perceptions. The fact that Refn is soon making a re-do of Logan’s Run with Gosling is a suggestion of a large-scaled cinema that’s aware of its kinetic powers, its artistic breadth, and its ability to kick it into the fifth gear.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Cinema Scope

“Hey, do you wanna see somethin’?”—Driver in Drive

In the middle of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, a film punctuated by extreme flourishes of violence and vengeance, there is a period of peace. It occurs when Driver (Ryan Gosling), a quietly contained guy who holds down three jobs—auto mechanic, movie stunt driver, and getaway driver-for-hire—is asked by his auto-shop boss (Bryan Cranston) to drive home customer and Driver’s neighbour Irene (Carey Mulligan) and her little boy. En route, Driver takes a surprising detour from the street down to the concrete banks of the Los Angeles River, one of the city’s most iconic images, a grand public-works project born out of vast and tragic flooding the city endured generations ago. The river, choked into a narrow canal and surrounded by an elegantly paved canyon, has been used in too many movies and TV shows to possibly count, most recently by Bruce La Bruce for daytime sequences of L.A. Zombie (2010). Driver, true to character, uses it as a racetrack and as a bit of stunt track—mildly, as a kid’s in the car, and he’s a gentleman at heart—but also as a road to get somewhere.

The typical deployment of the Los Angeles River in cinema is as a symbol of dead ends, final stops, the place where the city dies, and people along with it. Not so for Refn, for whom Los Angeles is a new city, a place of discovery. Viewed from the majestic prospect of a high angle in long-shot widescreen, Driver stops at the place where the concrete river ends and gives way to the wild river, a startling image even for native Angelenos. He knows these kinds of places, having driven everywhere (so, in reality, does Gosling, who knows the city expertly and drove Refn around town as research, inspiration, and preparation). Refn understands those many places in Los Angeles that make it fairly unique, and reverses the usual clichéd knock on the place as one long paved sprawl. Constantly, the paved cityscape surrenders to the natural world, sidewalks dissolve into dirt trails, roads simply stop, buildings reach their limit when faced with cliffsides, massive chaparral, impregnable mountain ranges that cut through the metropolitan area. Driver leads mother and son to the wild river for a Tom Sawyer afternoon under the sun, a Southern California utopia—the ultimate getaway—an idyll that defines Drive and Driver in fundamental ways.

Superficially an action movie, Drive is actually a film in search of romance, zigzagging through an obstacle course of fairy tale and myth, and a hall of mirrors in which characters can be read as fantasy projections of others while being aware of themselves as figures inside a myth. Beloved in Cannes after days of disappointing films in the competition, Drive was perhaps welcomed by some for the wrong reason: as some kind of new read on Melville’s Le samourai (1967), with Gosling processing Alain Delon’s stoic killer. For once, the director has a sound interpretation that he’s willing to share with whomever cares to listen: Refn correctly argues that Drive’s foundation is in fairy tale, particularly its thematic of a character’s discovery of his own heroism, which Driver finds through the course of nurturing and protecting Irene, who’s made paradoxically more vulnerable when her convict husband returns home from prison. The necessary elimination of dragons—in the form of Albert Brooks’ ice-cold mobster Bernie Rose and Ron Perlman’s put-upon mobster Nino, to say nothing of a few nameless hitmen along the way—doesn’t so much make Driver into a killer, although he wreaks revenge with frighteningly intelligent brutality. Rather, it transforms him into a mythical figure who satisfies the imaginings of those around him, including Irene, who can nevertheless only marvel at him while knowing she can never have him. This is vastly different from Melville’s heightened existential world of professional killers who function by a code and live like lone wolves, apparently free of the need for genuine and reciprocal human contact. Delon’s Samourai is a corporeal killing machine; Gosling’s Driver is a young man in formation, whose work comprises (per his three jobs) repair, escape, and entertainment, and who finds his self during a gauntlet that perhaps only he can survive—an accidental knight who slays the beast.

This is a far stretch from James Sallis’ novel on which Hossein Amini’s screenplay is based, and, as Refn describes it, wildly different from Amini’s previous drafts written as a potential Universal franchise for Hugh Jackman. Sallis’ superb, laconic book, hardboiled to the core, as affectionate toward its city as it is cynical about the city’s most famous (show) business, could have been adapted pretty closely, even with its obsessive (and perhaps needless) jumps in chronology. But a knowledge of the book is helpful in appreciating the grand achievement in American cinema that Drive is. Hollywood has always been open to the invasive notions of outsiders, particularly European directors with strong points of view. Lubitsch, Lang, Boorman, Preminger, Wilder, von Sternberg, Herzog, Verhoeven, and von Stroheim all managed to import their native sensibilities with little compromise into the Hollywood system, and generally thrived intact. Refn’s ambition is clearly to make big movies for large audiences by his own sometimes-radical standards, which include mixing the hyper-violent ecstasies of the Pusher trilogy (1996, 2004, 2005), highly theatrical characters like Tom Hardy’s Bronson (2008), dreamlike dances of death as in Valhalla Rising (2009), and the romance of transformation in Drive. His new film is an act of will, pulling a fine but fairly standard piece of high-class pulp into something richer and more dynamic, modern in its self-consciousness as a work of art and entertainment, and Wellesian in its capacity to astonish, shock, and tease the mind’s perceptions. The fact that Refn is soon making a re-do of Logan’s Run with Gosling is a suggestion of a large-scaled cinema that’s aware of its kinetic powers, its artistic breadth, and its ability to kick it into the fifth gear.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

James L. Neibaur: The Great Dictator

The Great Dictator

by James L. Neibaur

Cineaste

Released in 1940, a good dozen years after the talking-picture revolution, The Great Dictator shows silent-screen icon Charlie Chaplin finally conceding to the new format by confronting it head-on with a film that was both topical and challenging. Unlike Buster Keaton, Chaplin was not as interested in the technology of cinema as he was with character and narrative. While a fascinated Keaton wanted to experiment with talking pictures, Chaplin continued to release movies that were largely silent well after sound film had become the norm. Chaplin claimed, in interviews, that if his beloved Little Tramp character were allowed to have a specific language, he would no longer be a universal Everyman. Thus, his only releases during the 1930s—City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936)—were largely silent, save for music Chaplin himself composed, as well as carefully orchestrated sound effects. His choice to allow us to hear the Little Tramp’s voice in the latter film was via a musical number done in gibberish.

Chaplin’s success releasing silent films during the talking-picture era shows how much power the comedian had by that point in his career. Reports in movie-trade magazines as early as 1929 stated how theaters that were not yet equipped to show sound movies were losing business. Mediocre early talkies were drawing several times more than some of the best silent films. By the time Chaplin was filming Modern Times, studios were cutting up their dramatic silent features, which had been box-office successes only five years earlier, overdubbing silly music and wisecracking narration, and releasing them as sarcastic short comedies. Exhibitor H.E. Hoag stated in 1930: “A silent comedy is very flat now. In fact, for the past two years, my audiences seldom laughed out loud at a silent.”

The bigger studios hastily transformed recently shot silent features into talkies by dubbing in voices and sound effects. The smaller studios did not have the funds to accomplish this, and thus their silents of late 1929 and early 1930 received very little distribution, save for small-town theaters that were not yet equipped for sound. But by the 1930’s sound was so firmly established in the cinema that only someone with the status of Charlie Chaplin was able to pull off making a silent picture and enjoying a lofty level of success. One theater in Wisconsin reported record attendance for City Lights, despite snowstorms that closed roads. People were said to have walked through blizzard conditions to see the film.

Evidence has recently surfaced that Chaplin had considered making a talkie about colonialism in 1932, even to the point of having a manuscript prepared. But, for reasons we may never know, this film was not produced. By 1940, however, Chaplin decided it was time.

As the Third Reich came to power in Germany and began characterizing Jewish people negatively, word got back to Chaplin that a 1934 booklet entitled The Jews Are Watching You had been published, claiming that he was of Jewish heritage. A caricature of Chaplin, lengthening his nose and emphasizing his dark curly hair, referred to the comedian as a “little Jewish tumbler,” who was “as disgusting as he is boring.” Chaplin was not Jewish, but refused to deny it, believing such a denial would be “playing into the hands of the anti-Semites.” Friends had already been commenting on the fact that Hitler wore a mustache similar to Chaplin’s, and a rumor persisted that the dictator chose his facial hair specifically to resemble the beloved comedian. More intrigued than insulted, Chaplin chose to fight back using comedy.

As he composed the script, Chaplin arranged to play two roles in The Great Dictator, using his noted resemblance to Hitler as the axis of his film. The humble Jewish barber appears to be an extension of his classic Little Tramp (even to the point of being clad in similar dress). The barber’s lookalike is dictator Adenoid Hynkel. It would seem that the heartless persecution of Jewish people by Nazi storm-troopers would hardly lend itself to comedy, and Chaplin later admitted that, had he known more about the atrocities, he would not likely have made the film. But somehow Chaplin effectively balances the humor with the underlying message.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by James L. Neibaur

Cineaste

Released in 1940, a good dozen years after the talking-picture revolution, The Great Dictator shows silent-screen icon Charlie Chaplin finally conceding to the new format by confronting it head-on with a film that was both topical and challenging. Unlike Buster Keaton, Chaplin was not as interested in the technology of cinema as he was with character and narrative. While a fascinated Keaton wanted to experiment with talking pictures, Chaplin continued to release movies that were largely silent well after sound film had become the norm. Chaplin claimed, in interviews, that if his beloved Little Tramp character were allowed to have a specific language, he would no longer be a universal Everyman. Thus, his only releases during the 1930s—City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936)—were largely silent, save for music Chaplin himself composed, as well as carefully orchestrated sound effects. His choice to allow us to hear the Little Tramp’s voice in the latter film was via a musical number done in gibberish.

Chaplin’s success releasing silent films during the talking-picture era shows how much power the comedian had by that point in his career. Reports in movie-trade magazines as early as 1929 stated how theaters that were not yet equipped to show sound movies were losing business. Mediocre early talkies were drawing several times more than some of the best silent films. By the time Chaplin was filming Modern Times, studios were cutting up their dramatic silent features, which had been box-office successes only five years earlier, overdubbing silly music and wisecracking narration, and releasing them as sarcastic short comedies. Exhibitor H.E. Hoag stated in 1930: “A silent comedy is very flat now. In fact, for the past two years, my audiences seldom laughed out loud at a silent.”

The bigger studios hastily transformed recently shot silent features into talkies by dubbing in voices and sound effects. The smaller studios did not have the funds to accomplish this, and thus their silents of late 1929 and early 1930 received very little distribution, save for small-town theaters that were not yet equipped for sound. But by the 1930’s sound was so firmly established in the cinema that only someone with the status of Charlie Chaplin was able to pull off making a silent picture and enjoying a lofty level of success. One theater in Wisconsin reported record attendance for City Lights, despite snowstorms that closed roads. People were said to have walked through blizzard conditions to see the film.

Evidence has recently surfaced that Chaplin had considered making a talkie about colonialism in 1932, even to the point of having a manuscript prepared. But, for reasons we may never know, this film was not produced. By 1940, however, Chaplin decided it was time.

As the Third Reich came to power in Germany and began characterizing Jewish people negatively, word got back to Chaplin that a 1934 booklet entitled The Jews Are Watching You had been published, claiming that he was of Jewish heritage. A caricature of Chaplin, lengthening his nose and emphasizing his dark curly hair, referred to the comedian as a “little Jewish tumbler,” who was “as disgusting as he is boring.” Chaplin was not Jewish, but refused to deny it, believing such a denial would be “playing into the hands of the anti-Semites.” Friends had already been commenting on the fact that Hitler wore a mustache similar to Chaplin’s, and a rumor persisted that the dictator chose his facial hair specifically to resemble the beloved comedian. More intrigued than insulted, Chaplin chose to fight back using comedy.

As he composed the script, Chaplin arranged to play two roles in The Great Dictator, using his noted resemblance to Hitler as the axis of his film. The humble Jewish barber appears to be an extension of his classic Little Tramp (even to the point of being clad in similar dress). The barber’s lookalike is dictator Adenoid Hynkel. It would seem that the heartless persecution of Jewish people by Nazi storm-troopers would hardly lend itself to comedy, and Chaplin later admitted that, had he known more about the atrocities, he would not likely have made the film. But somehow Chaplin effectively balances the humor with the underlying message.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Best of the Left: Compilations of Reports on the Occupy Movement, Pts. 1-7 (September - November, 2011)

[A great collection of reports on the Occupy Movement -- thanks Jay Tomlinson! Check back at Best of the Left for future reports and for compilations on other subjects/themes]

#538 The 99 Percent Wakes Up (Occupy Wall St Part 1)

Act 1: Congrats to Wall St. Protesters – The Progressive Air Date: 9-27-11 Song 1: Hi – The Only Thing I Ever Wanted

Act 2: Irony of Police Attacks on Protestors – Jimmy Dore Air Date: 9-27-11

Song 2: Pumped Up Kicks – Torches

Act 3: World Economy Going to Hell – Dan Carlin Air Date: 9-28-11

Song 3: Eleanor Rigby (Strings Only) – Anthology 2

Act 4: Fox News Gives Wall Street Protesters the “Fair & Balanced” Treatment – Media Matters Air Date: 10-3-11

Act 5: Keith Olbermann reads first collective statement of Occupy Wall Street – Countdown

Song 5: The Times They Are A-Changin’ – The Essential Bob Dylan

Act 6: Protesting is a Priviledge? – Majority Report Air Date: 9-28-11

Song 6: Turtle (Bonobo Mix) – One Offs… Remixes & B Sides

Act 7: Fox Host says Tea Party was Organic, Occupy Wall Street is Not – Media Matters Air Date: 10-5-11

Act 8: Michael Moore says We oppose the way our economy is structured – Countdown

#539 We are the other 99 percent (Occupy Wall St Part 2)

Act 1: Police Are On The Wrong Side At The Occupy Wall Street Protests – Lee Camp Air Date: 9-25-11

Song 1: All These Things That I’ve Done – Hot Fuss

Act 2: Romney Would Complain About Class Warfare – The Progressive Air Date: 10-5-11

Song 2: Revolution – I Am Sam (Music from and Inspired By the Motion Picture)

Act 3: The Screaming Majority song on Occupy Wall St – Majority Report Air Date: 10-7-11

Song 3: Up nights – Amsterband

Act 4: The TRUTH About The Occupy Wall Street Protests – Lee Camp Air Date: 9-27-11

Song 4: Free to Decide – Stars – The Best of 1992-2002

Act 5: Panic of the plutocrats – Green News Report Air Date: 10-11-11