To watch Sicko online

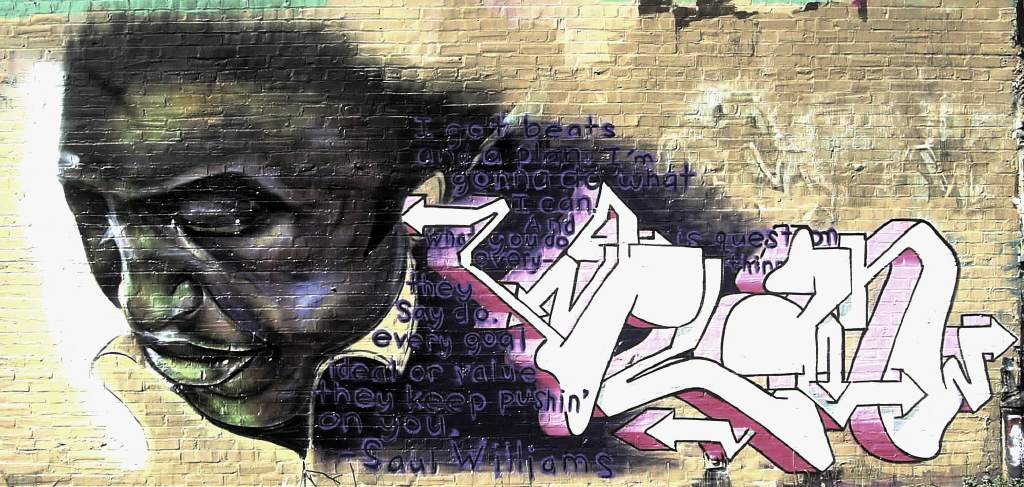

"My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel--it is, above all, to make you see." -- Joseph Conrad (1897)

On the twenty-fifth of September 1937, a depression moving from Newfoundland to the Baltic sent masses of warm, moist oceanic air into the corridor of the English Channel. At 5:19 P.M. a gust of wind from the west-southest uncovered the petticoat of old Henriette Puysoux, who was picking up potatos in her field; slapped the sun blind of the Cafe des Amis in Plancoet; banged a shutter on the house belonging to Dr. Bottereau alongside the wood of La Hunaudaie; turned over eight pages of Aristotle’s Meteorologica, which Michel Tournier was reading on the beach at Saint-Jacut; raised a cloud of dust and bits of straw on the road to Plelan; blew wet spray in the face of Jean Chauve as he was putting his boat out in the Bay of Arguenon; set the Pallet family’s underclothes bellying and dancing on the line where they were drying; started the wind pump racing at the Ferme des Mottes; and snatched a handful of gilded leaves off the silver birches in the garden of La Cassine. (9)

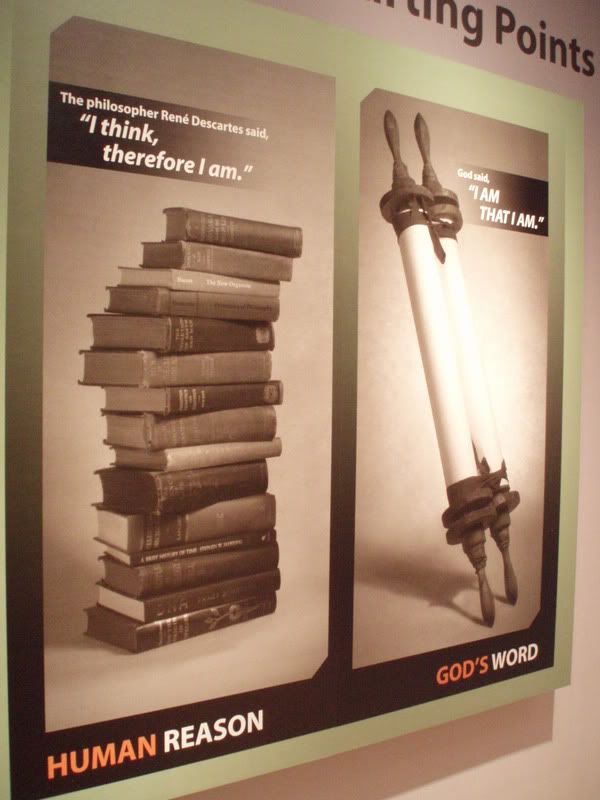

Culture is not just the expression of individual interests and orientations, manifested in groups according to rules and habits but it offers identification with a system of values. The construction of cultural memory and establishing a symbolic order through setting up mental and ideological spaces is a traditional practice of cultural engineering; symbolic scenarios generate reality by mediating an implicit political narrative and logic. Maps of the world radiating an aura of objectivity and marking out the ways of life are exploited as cognitive tools. An image of the world as simulation or map of reality can be highly inductive and that explains the investment in cultural representation. From historiography to education, perception is influenced by mental scenarios that establish the symbolic order. According to Edward Bernays, a pioneer of modern public relations, the only difference between education and propaganda is the point of view. "The advocacy of what we believe in is education. The advocacy of what we don�t believe is propaganda." The development in electronic communication and digital media allows for a global telepresence of values and behavioral norms and provides increasing possibilities of controlling public opinion by accelerating the flow of persuasive communication. Information is increasingly indistinguishable from propaganda, defined as "the manipulation of symbols as a means of influencing attitudes". Whoever controls the metaphors controls thought.

The ubiquitous flow of information is too fast to absorb and creating value in the economy of attention includes the artful use of directing perception to a certain area, to put some aspects in the spotlight in order to leave others in the dark. The increasing focus of attention on the spectacle makes everything disappear that is not within the predefined event horizon. Infosphere manipulation is also implemented through profound penetration of the communications landscape by agents of influence. Large scale operations to manage public opinion, to evoke psychological guiding motivations and to engineer consent or influence policy making have not been exclusive to the 20th century. Evidence of fictitious cultural reconstruction is abundant in the Middle Ages; recent findings on the magnitude of forgeries, the large scale faking of genealogies, official documents and codices attracted broad attention and media interest. In 12th century Europe in particular, pseudo historical documents were widely employed as tools of political legitimacy and psychological manipulation. According to some conservative estimates, the majority of all documents of this period were fictitious. With hindsight, whole empires could turn out to be products of cultural engineering. Moreover, writers such as Martin Bernal, author of "The Fabrication of Ancient Greece", have clearly demonstrated to what extent cultural propaganda and historical disinformation is contained in the work of European scholars. On the basis of racist ideas and a hidden political agenda historic scenarios were fabricated and cultural trajectories distorted in order to support the ideological hegemony of certain European elites.

The increasing informatization of society and economy is also the source of a growing relevance of culture, the cultural software in the psycho-political structure of influence. During the so-called cold war, too, issues of cultural hegemony were of importance. In publications such as "The Cultural Cold War" and "How America stole the Avant-garde" Frances Stonor Saunders and Serge Guilbaud offer a behind-the-scenes view of the cultural propaganda machine and provide a sense of the extravagance with which this mission was carried out. Interestingly there were efforts to support progressive and liberal positions as bridgehead against the "communist threat". If one chooses to believe some contemporary investigative historical analyses, it seems that there was hardly a major western progressive cultural magazine in the Fifties and Sixties that would not have been founded or supported by a cover organization of intelligence services or infiltrated by such agencies. In the light of this, the claim made by Cuba at the UNESCO world conference in Havana 1998, according to which culture is the "weapon of the 21st century" does not seem unfounded.

Information Peacekeeping has been described as the "purest form of war" in the extensive military literature on information war. From cold war to code war, the construction of myths, with the intention of harmonizing subjective experience of the environment, is used for integration and motivation in conflict management. While "intelligence" is often characterized as the virtual substitute of violence in the information society, Information Peacekeeping, the control of the psycho-cultural parameters through the subliminal power of definition in intermediation and interpretation is considered the most modern form of warfare.

O:

OK this is what I was going to say about the film - that I got it in a way that I hadn't gotten it before. Now don't you love when that happens. When you just go "Ooo! I got it!" Because you know the word "socialism" really stirs up...

MM:

[Scarily] Socialized Medicine...

O:

Socialized Medicine

MM:

[Scarily] Ooo...

O: And then when you showed the example of [how] we have socialized activities in this country. The fire department - we don't pay for a fire department. We don't pay for the police department. We don't pay for public schools.

MM:

And it's universal.

O:

We don't pay for the library. And it's universal - universal is for everybody.

MM:

Right.

O:

And so the very idea of extending that to the care of people is really something that I have to honestly say that I hadn't thought about it because I'm one of those people, "I got mine," so I wasn't thinking about who didn't have theirs. Really. Right.

MM:

And we don't expect the fire department to turn a profit. It would be an appalling thought, and the reason we don't is because it's a life and death issue. Well, health care is a life and death issue.

O:

Yeah.

MM:

And that's why turning a profit has to be removed from the system.