"My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel--it is, above all, to make you see." -- Joseph Conrad (1897)

Thursday, February 26, 2009

Merriam-Webster's Concise Dictionary of English Usage: a, an

(I'm going to read this front-to-back and I learn best by writing, reading and restating...)

Merriam-Webster's Concise Dictionary of English Usage: The Essentials of Clear Expression

The basic rules are these: use a before a consonant sound; use an before a vowel sound. Before a letter or an acronym or before numerals, choose a or an according to the way the letter or numeral is pronounced: an FDA directive, a U.N. resolution, a $5.00 bill.

Merriam-Webster's Concise Dictionary of English Usage: The Essentials of Clear Expression

The basic rules are these: use a before a consonant sound; use an before a vowel sound. Before a letter or an acronym or before numerals, choose a or an according to the way the letter or numeral is pronounced: an FDA directive, a U.N. resolution, a $5.00 bill.

Alvaro Vargas Llosa: What the overly PC critics of 'Slumdog Millionare' still don't understand

A Bollywood Ending: What the overly PC critics of 'Slumdog Millionare' still don't understand.

by Alvaro Vargas Llosa

The New Republic

...

The critics forget a few facts. The film is based on the novel "Q&A" by Vikas Swarup, an Indian diplomat. Although the director and the scriptwriter, both British, made changes in their adaptation of the story, they kept the essentials: An Indian slum orphan is arrested for getting too many answers right in a TV quiz show and the subsequent narration of his journey reveals to us that his correct answers did not come from cheating but from street wisdom picked up in a succession of experiences that attest to his instinct for survival. Not to mention all the on- and off-camera Indians associated with the movie, who feel proud of their role in it.

...

The charge that "Slumdog Millionaire" exploits Mumbai's poverty is so absurd that by the same token Charles Dickens' entire body of work would have to be invalidated as a defamation of 19th-century England. Like all accomplished stories, "Slumdog Millionaire" is probably resonating with audiences because it gives a glimpse of complex truths and tells us something about ourselves that we had trouble defining. In that sense, the Motion Picture Academy did not honor a "foreign" film, but one strangely familiar.

To Read the Rest of the Commentary

by Alvaro Vargas Llosa

The New Republic

...

The critics forget a few facts. The film is based on the novel "Q&A" by Vikas Swarup, an Indian diplomat. Although the director and the scriptwriter, both British, made changes in their adaptation of the story, they kept the essentials: An Indian slum orphan is arrested for getting too many answers right in a TV quiz show and the subsequent narration of his journey reveals to us that his correct answers did not come from cheating but from street wisdom picked up in a succession of experiences that attest to his instinct for survival. Not to mention all the on- and off-camera Indians associated with the movie, who feel proud of their role in it.

...

The charge that "Slumdog Millionaire" exploits Mumbai's poverty is so absurd that by the same token Charles Dickens' entire body of work would have to be invalidated as a defamation of 19th-century England. Like all accomplished stories, "Slumdog Millionaire" is probably resonating with audiences because it gives a glimpse of complex truths and tells us something about ourselves that we had trouble defining. In that sense, the Motion Picture Academy did not honor a "foreign" film, but one strangely familiar.

To Read the Rest of the Commentary

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Toronto J-Film Pow Wow: Our Top Ten Favorite Japanese Horror Films

Our Top Ten Favorite Japanese Horror Films

Toronto J-Film Pow Wow

While Akira Kurosawa's "Rashomon" was widely dubbed "The film that introduced the world to Japanese cinema" during the 20th-century it could easily be argued that films like Kiyoshi Kurosawa's "Kairo (Pulse)", Hideo Nakata's "Ringu" and Takashi Shimizu's "Ju-On" were the films that introduced a whole new generation to Japanese cinema in the 21st-century. At the start of the new millenium audiences had already been haunted, stalked and dismembered by a gallery of boogie men from Leatherface to Freddy Krueger and frankly the standard scares were getting a bit stale. In an attempt to devise new ways to keep people sleeping with the light on Hollywood turned East and found inspiration in the atmospheric and exotic horror being produced in Japan. The major studios started buying up the distribution and remake rights for a wide variety of films from a diverse group of filmmaker like the names mentioned above, but also more "extreme" directors like Takashi Miike, Shinya Tsukamoto and Sion Sono. The work of this loose group was was dubbed "J-Horror" and for a few years it was the hottest thing in genre filmmaking. Unfortunately we live in hyper-accelerated and fickle times and once the best horror from Japan had been bought up and recycled studio execs were left picking over whatever sub par product was left and the hot new sub-genre quickly fizzled out.

Regardless of the fact that J-Horror has gone past its sell-by-date that burst of attention at the start of the decade opened doors for a wide variety of not only Japanese but Asian films in general to make their way West and horror fans now have a whole new crop of cinema classics that can join "The Exorcist", "The Shining" and "Night of the Living Dead" in the pantheon of fear. To honour the genre that got so many of you interested in Japanese cinema in the first place we at the Toronto J-Film Pow-Wow wanted to pull together our list of Top Ten Favorite Japanese Horror Films from across the history of Japanese cinema. Proceed at your own risk...

To See the List and Read the Descriptions

Toronto J-Film Pow Wow

While Akira Kurosawa's "Rashomon" was widely dubbed "The film that introduced the world to Japanese cinema" during the 20th-century it could easily be argued that films like Kiyoshi Kurosawa's "Kairo (Pulse)", Hideo Nakata's "Ringu" and Takashi Shimizu's "Ju-On" were the films that introduced a whole new generation to Japanese cinema in the 21st-century. At the start of the new millenium audiences had already been haunted, stalked and dismembered by a gallery of boogie men from Leatherface to Freddy Krueger and frankly the standard scares were getting a bit stale. In an attempt to devise new ways to keep people sleeping with the light on Hollywood turned East and found inspiration in the atmospheric and exotic horror being produced in Japan. The major studios started buying up the distribution and remake rights for a wide variety of films from a diverse group of filmmaker like the names mentioned above, but also more "extreme" directors like Takashi Miike, Shinya Tsukamoto and Sion Sono. The work of this loose group was was dubbed "J-Horror" and for a few years it was the hottest thing in genre filmmaking. Unfortunately we live in hyper-accelerated and fickle times and once the best horror from Japan had been bought up and recycled studio execs were left picking over whatever sub par product was left and the hot new sub-genre quickly fizzled out.

Regardless of the fact that J-Horror has gone past its sell-by-date that burst of attention at the start of the decade opened doors for a wide variety of not only Japanese but Asian films in general to make their way West and horror fans now have a whole new crop of cinema classics that can join "The Exorcist", "The Shining" and "Night of the Living Dead" in the pantheon of fear. To honour the genre that got so many of you interested in Japanese cinema in the first place we at the Toronto J-Film Pow-Wow wanted to pull together our list of Top Ten Favorite Japanese Horror Films from across the history of Japanese cinema. Proceed at your own risk...

To See the List and Read the Descriptions

Film School: THAVISOUK PHRASAVATH co-director of THE BETRAYAL

THAVISOUK PHRASAVATH co-director of THE BETRAYAL

Film School (Irvine, CA: KUCI)

Hosts: Nathan Callahan and Mike Kaspar

An interview with THAVISOUK PHRASAVATH co-director of THE BETRAYAL — the epic story of a family forced to emigrate from Laos after the chaos of the secret air war waged by the U.S. during the Vietnam War. A Lao prophecy says, "A time will come when the universe will break, piece by piece, the world will change beyond what we know." That time came for the small country of Laos with the clandestine involvement of the United States during the Vietnam War. By 1973, three million tons of bombs had been dropped on Laos in the fight to overcome the North Vietnamese, more than the total used during both world wars. With the rise of a Communist government in Laos, killings and arrests became common among those affiliated with the former government and the Americans. Families were torn apart-some finally emigrating to the U.S. In a collaboration spanning more than 20 years, Phrasavath the main subject of the film worked with co-director Ellen Kuras. Phrasavath takes us through his youth, his escape from persecution and arrest in Laos, his family's reunion and their journey as immigrants to America, and the second war they had to fight on the streets of New York City. Drawing on the techniques of experimental film and the traditions of Laotian culture, The Betrayal is a tale about a country, a family, and a young man who discovers the power and resilience of the human spirit.

To Listen to the Interview (MP3)

Film School (Irvine, CA: KUCI)

Hosts: Nathan Callahan and Mike Kaspar

An interview with THAVISOUK PHRASAVATH co-director of THE BETRAYAL — the epic story of a family forced to emigrate from Laos after the chaos of the secret air war waged by the U.S. during the Vietnam War. A Lao prophecy says, "A time will come when the universe will break, piece by piece, the world will change beyond what we know." That time came for the small country of Laos with the clandestine involvement of the United States during the Vietnam War. By 1973, three million tons of bombs had been dropped on Laos in the fight to overcome the North Vietnamese, more than the total used during both world wars. With the rise of a Communist government in Laos, killings and arrests became common among those affiliated with the former government and the Americans. Families were torn apart-some finally emigrating to the U.S. In a collaboration spanning more than 20 years, Phrasavath the main subject of the film worked with co-director Ellen Kuras. Phrasavath takes us through his youth, his escape from persecution and arrest in Laos, his family's reunion and their journey as immigrants to America, and the second war they had to fight on the streets of New York City. Drawing on the techniques of experimental film and the traditions of Laotian culture, The Betrayal is a tale about a country, a family, and a young man who discovers the power and resilience of the human spirit.

To Listen to the Interview (MP3)

University of Kentucky Spring Sustainability Series: Vandana Shiva (3/4)

(Courtesy of Rebecca Glasscock)

On Wednesday, March 4th, Dr. Vandana Shiva will deliver the Spring Sustainability Lecture at 7pm in Memorial Hall at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Shiva is an internationally-renowned scientist, author and activist with strong interests in sustainable development, feminist theory, alternative globalization and bioengineering. She is widely regarded as one of the brightest minds working in the interdisciplinary field of sustainability. Dr. Shiva is also the founder of Navdanya, a participatory research initiative to provide direction and support to environmental activism.

This is the second lecture in the President’s Sustainability Lecture Series and Dr. Shiva will be discussing the importance of higher education’s role in sustainable development.

For more information about Vandana Shiva.

On Wednesday, March 4th, Dr. Vandana Shiva will deliver the Spring Sustainability Lecture at 7pm in Memorial Hall at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Shiva is an internationally-renowned scientist, author and activist with strong interests in sustainable development, feminist theory, alternative globalization and bioengineering. She is widely regarded as one of the brightest minds working in the interdisciplinary field of sustainability. Dr. Shiva is also the founder of Navdanya, a participatory research initiative to provide direction and support to environmental activism.

This is the second lecture in the President’s Sustainability Lecture Series and Dr. Shiva will be discussing the importance of higher education’s role in sustainable development.

For more information about Vandana Shiva.

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

University of Kentucky Socialist Student Union Lecture Series: "Socialism and the Economic Crisis: Whose way forward?" (2/25)

"Socialism and the Economic Crisis: Whose way forward?"

part of The Socialist Student Union Lecture Series

Host:

U.K. Socialist Student Union

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

5:00pm - 6:00pm

Room 111 in UK Student Center

Avenue of Champions/Euclid Avenue

Lexington, KY

Contact Info

standinsolidarity@yahoo.com

You are invited to the lecture, "Socialism and the Economic Crisis: Whose way forward?" presented by Aaron Kappeler and Patrick Bigger.

The lecture will discuss the socialist movement and the struggle for a dual power in light of current economic events, specifically the significance of the shift from neoliberal to keynesian style policies as a tactic for dealing with the crisis of accumulation. The lecture will also include a discussion on socialist strategy.

Light refreshments will be served. Drinks to follow at location TBA.

Lecturer Bios:

Aaron Kappeler is a Ph.D. candidate in Anthropology and Political Economy at the University of Toronto. His current research centers on the agrarian reform in Venezuela and the transformation of the state, society and livelihood in the Bolivarian revolution. He can be reached at aaron dot kappeler at utoronto dot ca

Patrick Bigger is a Geography student at the University of Kentucky.

part of The Socialist Student Union Lecture Series

Host:

U.K. Socialist Student Union

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

5:00pm - 6:00pm

Room 111 in UK Student Center

Avenue of Champions/Euclid Avenue

Lexington, KY

Contact Info

standinsolidarity@yahoo.com

You are invited to the lecture, "Socialism and the Economic Crisis: Whose way forward?" presented by Aaron Kappeler and Patrick Bigger.

The lecture will discuss the socialist movement and the struggle for a dual power in light of current economic events, specifically the significance of the shift from neoliberal to keynesian style policies as a tactic for dealing with the crisis of accumulation. The lecture will also include a discussion on socialist strategy.

Light refreshments will be served. Drinks to follow at location TBA.

Lecturer Bios:

Aaron Kappeler is a Ph.D. candidate in Anthropology and Political Economy at the University of Toronto. His current research centers on the agrarian reform in Venezuela and the transformation of the state, society and livelihood in the Bolivarian revolution. He can be reached at aaron dot kappeler at utoronto dot ca

Patrick Bigger is a Geography student at the University of Kentucky.

Benjamin R. Barber: The Educated Student--Global Citizen or Global Consumer?

The Educated Student: Global Citizen or Global Consumer?

by Benjamin R. Barber

Liberal Education (Spring, 2002); available from Find Articles

I WANT TO TRACE A QUICK TRAJECTORY from July 4, 1776 to Sept. 11, 2001. It takes us from the Declaration of Independence to the declaration of interdependence--not one that is actually yet proclaimed but one that we educators need to begin to proclaim from the pulpits of our classrooms and administrative suites across America.

In 1776 it was all pretty simple for people who cared about both education and democracy. There was nobody among the extraordinary group of men who founded this nation who did not know that democracy--then an inventive, challenging, experimental new system of government--was dependent for its success not just on constitutions, laws, and institutions, but dependent for its success on the quality of citizens who would constitute the new republic. Because democracy depends on citizenship, the emphasis then was to think about what and how to constitute a competent and virtuous citizen body. That led directly, in almost every one of the founders' minds, to the connection between citizenship and education.

Whether you look at Thomas Jefferson in Virginia or John Adams in Massachusetts, there was widespread agreement that the new republic, for all of the cunning of its inventive and experimental new Constitution, could not succeed unless the citizenry was well educated. That meant that in the period after the Revolution but before the ratification of the Constitution, John Adams argued hard for schools for every young man in Massachusetts (it being the case, of course, that only men could be citizens). And in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson made the same argument for public schooling for every potential citizen in America, founding the first great public university there. Those were arguments that were uncontested.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century this logic was clear in the common school movement and later, in the land grant colleges. It was clear in the founding documents of every religious, private, and public higher education institution in this country. Colleges and universities had to be committed above all to the constituting of citizens. That's what education was about. The other aspects of it--literacy, knowledge, and research--were in themselves important. Equally important as dimensions of education and citizenship was education that would make the Bill of Rights real, education that would make democracy succeed.

It was no accident that in subsequent years, African Americans and then women struggled for a place and a voice in this system, and the key was always seen as education. If women were to be citizens, then women's education would have to become central to suffragism. After the Civil War, African Americans were given technical liberty but remained in many ways in economic servitude. Education again was seen as the key. The struggle over education went on, through Plessy vs. Ferguson in 1896--separate, but equal--right down to the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education, which declared separate but equal unconstitutional.

In a way our first 200 years were a clear lesson in the relationship between democracy, citizenship, and education, the triangle on which the freedom of America depended. But sometime after the Civil War with the emergence of great corporations and of an economic system organized around private capital, private labor, and private markets, and with the import from Europe of models of higher education devoted to scientific research, we began to see a gradual change in the character of American education generally and particularly the character of higher education in America's colleges and universities. From the founding of Johns Hopkins at the end of the nineteenth century through today we have witnessed the professionalization, the bureaucratization, the privatization, the commercialization, and the individualization of education. Civics stopped being the envelope in which education was put and became instead a footnote on the letter that went inside and nothing more than that.

With the rise of industry, capitalism, and a market society, it came to pass that young people were exposed more and more to tutors other than teachers in their classrooms or even those who were in their churches, their synagogues--and today, their mosques as well. They were increasingly exposed to the informal education of popular opinion, of advertising, of merchandising, of the entertainment industry. Today it is a world whose messages come at our young people from those ubiquitous screens that define modem society and have little to do with anything that you teach. The large screens of the multiplex promote content determined not just by Hollywood but by multinational corporations that control information, technology, communication, sports, and entertainment. About ten of those corporations control over 60 to 70 percent of what appears on those screens.

Then, too, there are those medium-sized screens, the television sets that peek from every room of our homes. That's where our children receive not the twenty-eight to thirty hours a week of instruction they might receive in primary and secondary school, or the six or nine hours a week of classroom instruction they might get in college, but where they get anywhere from forty to seventy hours a week of ongoing "information," "knowledge," and above all, entertainment. The barriers between these very categories of information and entertainment are themselves largely vanished.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by Benjamin R. Barber

Liberal Education (Spring, 2002); available from Find Articles

I WANT TO TRACE A QUICK TRAJECTORY from July 4, 1776 to Sept. 11, 2001. It takes us from the Declaration of Independence to the declaration of interdependence--not one that is actually yet proclaimed but one that we educators need to begin to proclaim from the pulpits of our classrooms and administrative suites across America.

In 1776 it was all pretty simple for people who cared about both education and democracy. There was nobody among the extraordinary group of men who founded this nation who did not know that democracy--then an inventive, challenging, experimental new system of government--was dependent for its success not just on constitutions, laws, and institutions, but dependent for its success on the quality of citizens who would constitute the new republic. Because democracy depends on citizenship, the emphasis then was to think about what and how to constitute a competent and virtuous citizen body. That led directly, in almost every one of the founders' minds, to the connection between citizenship and education.

Whether you look at Thomas Jefferson in Virginia or John Adams in Massachusetts, there was widespread agreement that the new republic, for all of the cunning of its inventive and experimental new Constitution, could not succeed unless the citizenry was well educated. That meant that in the period after the Revolution but before the ratification of the Constitution, John Adams argued hard for schools for every young man in Massachusetts (it being the case, of course, that only men could be citizens). And in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson made the same argument for public schooling for every potential citizen in America, founding the first great public university there. Those were arguments that were uncontested.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century this logic was clear in the common school movement and later, in the land grant colleges. It was clear in the founding documents of every religious, private, and public higher education institution in this country. Colleges and universities had to be committed above all to the constituting of citizens. That's what education was about. The other aspects of it--literacy, knowledge, and research--were in themselves important. Equally important as dimensions of education and citizenship was education that would make the Bill of Rights real, education that would make democracy succeed.

It was no accident that in subsequent years, African Americans and then women struggled for a place and a voice in this system, and the key was always seen as education. If women were to be citizens, then women's education would have to become central to suffragism. After the Civil War, African Americans were given technical liberty but remained in many ways in economic servitude. Education again was seen as the key. The struggle over education went on, through Plessy vs. Ferguson in 1896--separate, but equal--right down to the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education, which declared separate but equal unconstitutional.

In a way our first 200 years were a clear lesson in the relationship between democracy, citizenship, and education, the triangle on which the freedom of America depended. But sometime after the Civil War with the emergence of great corporations and of an economic system organized around private capital, private labor, and private markets, and with the import from Europe of models of higher education devoted to scientific research, we began to see a gradual change in the character of American education generally and particularly the character of higher education in America's colleges and universities. From the founding of Johns Hopkins at the end of the nineteenth century through today we have witnessed the professionalization, the bureaucratization, the privatization, the commercialization, and the individualization of education. Civics stopped being the envelope in which education was put and became instead a footnote on the letter that went inside and nothing more than that.

With the rise of industry, capitalism, and a market society, it came to pass that young people were exposed more and more to tutors other than teachers in their classrooms or even those who were in their churches, their synagogues--and today, their mosques as well. They were increasingly exposed to the informal education of popular opinion, of advertising, of merchandising, of the entertainment industry. Today it is a world whose messages come at our young people from those ubiquitous screens that define modem society and have little to do with anything that you teach. The large screens of the multiplex promote content determined not just by Hollywood but by multinational corporations that control information, technology, communication, sports, and entertainment. About ten of those corporations control over 60 to 70 percent of what appears on those screens.

Then, too, there are those medium-sized screens, the television sets that peek from every room of our homes. That's where our children receive not the twenty-eight to thirty hours a week of instruction they might receive in primary and secondary school, or the six or nine hours a week of classroom instruction they might get in college, but where they get anywhere from forty to seventy hours a week of ongoing "information," "knowledge," and above all, entertainment. The barriers between these very categories of information and entertainment are themselves largely vanished.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

John Lennon: I Am the Walrus

(Courtesy of Rebecca Glasscock)

Watch Amazing Oscar-Nominated Short "I Met the Walrus"

TruthOut

Background/Description for the Video

Watch Amazing Oscar-Nominated Short "I Met the Walrus"

TruthOut

Background/Description for the Video

Conservatism I Support: Wendell Berry

(For my Kentucky students)

Mr. Wendell Berry of Kentucky

Wendell Berry: The Way of Ignorance

Wendell Berry: Open Letter on the Proposed Plan to Clear-Cut 800 Acres of Robinson Forest

Thinking About the Purpose of Education with Maxine Greene and Wendell Berry

“The Agrarian Standard.” Orion (2002)

“Christianity and the Survival of Creation.” Cross Currents (Summer 1993)

A Citizen’s Response to the National Security Strategy of the United States of America.” Orion (March/April 2003)

“Conserving Communities.”

“The Failure of War.” Yes (Winter 2002)

“A Few Words in Favor of Edward Abbey.” (1985)

“For the Love of the Land.” Sierra Magazine (May/June 2002)

“Getting Along With Animals.” The New Farm (September/October 1979):

“Global Problems, Local Solutions.” Resurgence (May/June 2001)

“Health is Membership.” (Delivered as a speech at a conference, "Spirituality and Healing", at Louisville, Kentucky, on October 17, 1994)

“The Idea of a Local Economy.” Orion (2002)

“In Distrust of Movements.” Resurgence (January/February 2000)

“The Joys of Sales Resistance”

“Lest We Forget.” (Excerpt from a Short Story: 1992):

“Life is a Miracle: Classification in Science.” Whole Earth Review (Fall 2000)

“Peaceableness Toward Enemies: Some Notes on the Gulf War.” (1991)

“The Pleasures of Eating.”

“The Prejudice Against Country People.” Progressive (April 2002):

“Private Property and Common Wealth.”

“Thoughts in the Presence of Fear.” Orion (2001)

“Visions for Rural Kentucky.” Whole Earth Review (Winter 1998)

Lannan Readings & Conversations: Wendell Berry with Jack Shoemaker

Wendell Berry: Compromise, Hell!

Wendell Berry: Excerpts from “The Work of Local Culture”

Mark Engler: Why Wendell Berry Matters

T.C. Boyle, Orion, Wendell Berry, Fear, Local Economy, James Howard Kunstler, Prozac, and A Friend of the Earth

Mr. Wendell Berry of Kentucky

Wendell Berry: The Way of Ignorance

Wendell Berry: Open Letter on the Proposed Plan to Clear-Cut 800 Acres of Robinson Forest

Thinking About the Purpose of Education with Maxine Greene and Wendell Berry

“The Agrarian Standard.” Orion (2002)

“Christianity and the Survival of Creation.” Cross Currents (Summer 1993)

A Citizen’s Response to the National Security Strategy of the United States of America.” Orion (March/April 2003)

“Conserving Communities.”

“The Failure of War.” Yes (Winter 2002)

“A Few Words in Favor of Edward Abbey.” (1985)

“For the Love of the Land.” Sierra Magazine (May/June 2002)

“Getting Along With Animals.” The New Farm (September/October 1979):

“Global Problems, Local Solutions.” Resurgence (May/June 2001)

“Health is Membership.” (Delivered as a speech at a conference, "Spirituality and Healing", at Louisville, Kentucky, on October 17, 1994)

“The Idea of a Local Economy.” Orion (2002)

“In Distrust of Movements.” Resurgence (January/February 2000)

“The Joys of Sales Resistance”

“Lest We Forget.” (Excerpt from a Short Story: 1992):

“Life is a Miracle: Classification in Science.” Whole Earth Review (Fall 2000)

“Peaceableness Toward Enemies: Some Notes on the Gulf War.” (1991)

“The Pleasures of Eating.”

“The Prejudice Against Country People.” Progressive (April 2002):

“Private Property and Common Wealth.”

“Thoughts in the Presence of Fear.” Orion (2001)

“Visions for Rural Kentucky.” Whole Earth Review (Winter 1998)

Lannan Readings & Conversations: Wendell Berry with Jack Shoemaker

Wendell Berry: Compromise, Hell!

Wendell Berry: Excerpts from “The Work of Local Culture”

Mark Engler: Why Wendell Berry Matters

T.C. Boyle, Orion, Wendell Berry, Fear, Local Economy, James Howard Kunstler, Prozac, and A Friend of the Earth

Fora TV: Robert Reich -- 2009 Economic Forecast

Robert Reich: 2009 Economic Forecast

Fora TV

As the economy nose-dives into a crisis of unknown depths, hear renowned economist and former Secretary of Labor Reich lay out his thoughts on what lurks around the financial corner in 2009.

Drawing on his years of experience both in and out of the political sphere, and sifting through the mountain of financial data, fiscal indicators, and government spin, Reich - who has been rumored as a contender for a position in the Obama administration - will cut through the hysteria and hyperbole to reveal where we're headed in '09

To Listen to the Speech

Fora TV

As the economy nose-dives into a crisis of unknown depths, hear renowned economist and former Secretary of Labor Reich lay out his thoughts on what lurks around the financial corner in 2009.

Drawing on his years of experience both in and out of the political sphere, and sifting through the mountain of financial data, fiscal indicators, and government spin, Reich - who has been rumored as a contender for a position in the Obama administration - will cut through the hysteria and hyperbole to reveal where we're headed in '09

To Listen to the Speech

Dave Kehr: Filmmaking at 90 Miles Per Hour

Filmmaking at 90 Miles Per Hour

by Dave Kehr

New York Times

...

Mr. Friedkin was a rising young filmmaker with four features (his unlikely debut was the 1967 Sonny and Cher vehicle, “Good Times”) and several documentaries to his credit when the producer Philip D’Antoni approached him about “The French Connection.” The story, essentially true, was derived from a book by Robin Moore that described how two narcotics detectives, Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, broke up a drug smuggling ring in the early 1960s, resulting in a record seizure: 120 pounds of heroin, worth more than $32 million.

“We felt, at the time, that the story had everything for a great police thriller except for one thing, and that was a great action scene,” Mr. Friedkin said. “Because it was mostly about an investigation that took place between 1960 and 1962, it was mostly listening in on wiretaps, following guys. There was no action. It was all police work.”

As the producer of “Bullitt” (1968), with its famous car chase through San Francisco, Mr. D’Antoni knew something about the importance of action. Joining Mr. Friedkin in Brooklyn for the DVD shoot, Mr. D’Antoni reminded him about a brainstorming session: “I remember meeting you at your apartment, and we went for a walk, maybe 50 blocks. And somewhere along the line an elevated train went by. You said, what about doing this? We got so excited we raced back to Ernest Tidyman, who was our screenwriter, and page by page we gave him our version of what the chase would be like. Later, when you shot it, it was changed three times again.”

The concept evolved into a parallel setup: as the sniper commandeered a train on the tracks above, forcing the motorman to drive at top speed, Popeye would hijack a passing car on the avenue below, and try to head the train off at the next station.

The car was driven by Bill Hickman, a veteran stunt coordinator who died in 1986. “Bill Hickman drove the car at 90 miles an hour,” Mr. Friedkin recalled. “I was in the back seat holding a camera over his shoulder, focused on the street ahead. There was a camera in the front seat looking out the window, and another one on the front bumper. The reason I handled the camera was because the camera operator and the director of photography both had families with children, and I didn’t.”

Riding in the shotgun seat was Randy Jurgensen, a police officer moonlighting as a technical advisor for the film. (Later Mr. Friedkin would base “Cruising” on one of Mr. Jurgensen’s cases.)

“We took off, with Billy telling Bill Hickman, ‘Give it to me, come on, you can do it, show me!’ ” Mr. Jurgensen said in an interview. “We had a police siren on top that people could hear, so that those who were able to get out of the way, could.”

There were no permits and no planning — just sheer nerve. “After 26 blocks, from Bay 50th to Bay 24th Street, I ran out of film, but I knew I had enough,” Mr. Friedkin said. “The fact that we never hurt anybody in the chase run, the way it was poised for disaster, this was a gift from the Movie God. Everything happened on the fly. We would never do this again. Nor should it ever be attempted in that way again.”

...

To Read the Rest of the Article and See Video Commentaries/Trailers

by Dave Kehr

New York Times

...

Mr. Friedkin was a rising young filmmaker with four features (his unlikely debut was the 1967 Sonny and Cher vehicle, “Good Times”) and several documentaries to his credit when the producer Philip D’Antoni approached him about “The French Connection.” The story, essentially true, was derived from a book by Robin Moore that described how two narcotics detectives, Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, broke up a drug smuggling ring in the early 1960s, resulting in a record seizure: 120 pounds of heroin, worth more than $32 million.

“We felt, at the time, that the story had everything for a great police thriller except for one thing, and that was a great action scene,” Mr. Friedkin said. “Because it was mostly about an investigation that took place between 1960 and 1962, it was mostly listening in on wiretaps, following guys. There was no action. It was all police work.”

As the producer of “Bullitt” (1968), with its famous car chase through San Francisco, Mr. D’Antoni knew something about the importance of action. Joining Mr. Friedkin in Brooklyn for the DVD shoot, Mr. D’Antoni reminded him about a brainstorming session: “I remember meeting you at your apartment, and we went for a walk, maybe 50 blocks. And somewhere along the line an elevated train went by. You said, what about doing this? We got so excited we raced back to Ernest Tidyman, who was our screenwriter, and page by page we gave him our version of what the chase would be like. Later, when you shot it, it was changed three times again.”

The concept evolved into a parallel setup: as the sniper commandeered a train on the tracks above, forcing the motorman to drive at top speed, Popeye would hijack a passing car on the avenue below, and try to head the train off at the next station.

The car was driven by Bill Hickman, a veteran stunt coordinator who died in 1986. “Bill Hickman drove the car at 90 miles an hour,” Mr. Friedkin recalled. “I was in the back seat holding a camera over his shoulder, focused on the street ahead. There was a camera in the front seat looking out the window, and another one on the front bumper. The reason I handled the camera was because the camera operator and the director of photography both had families with children, and I didn’t.”

Riding in the shotgun seat was Randy Jurgensen, a police officer moonlighting as a technical advisor for the film. (Later Mr. Friedkin would base “Cruising” on one of Mr. Jurgensen’s cases.)

“We took off, with Billy telling Bill Hickman, ‘Give it to me, come on, you can do it, show me!’ ” Mr. Jurgensen said in an interview. “We had a police siren on top that people could hear, so that those who were able to get out of the way, could.”

There were no permits and no planning — just sheer nerve. “After 26 blocks, from Bay 50th to Bay 24th Street, I ran out of film, but I knew I had enough,” Mr. Friedkin said. “The fact that we never hurt anybody in the chase run, the way it was poised for disaster, this was a gift from the Movie God. Everything happened on the fly. We would never do this again. Nor should it ever be attempted in that way again.”

...

To Read the Rest of the Article and See Video Commentaries/Trailers

Cormac Deane: The Embedded Screen and the State of Exception: Counterterrorist Narratives and the War on Terror

(I came across this essay as I was researching into the process and effects of "framing" knowledge for my students who are wrestling with ideological positions [their own and their sources] in their history projects. This was a pleasant surprise in that it demonstrates how "form" is just as important as [and complementary of] content. The essay also engages Slavoj Zizek's conception of the performative clustering effect of ideological keywords, Giorgio Agamben's analysis of the concept of the "state of exception," and how power is asserted and expressed through rhetorical-paradigms. This is a initial insight that should be explored...)

The Embedded Screen and the State of Exception: Counterterrorist Narratives and the War on Terror

by Cormac Deane

Refractory (Melbourne University, Australia)

Abstract: The embedded screen is a key feature of contemporary film and television texts featuring ‘terrorism’. Recurring chronotopes in these narratives, such as the control room and television news programmes, present us with frames within frames that have two complementary functions. First, embedded frames enact circular modes of logic, such as tautology and autology, which are crucial in the creation of a coherent notion of ‘terrorism’. Second, embedded frames are the screen-manifestation of the legal concept of the state of exception, which must be invoked so that the forces of law and order can take extraordinary measures in the face of a ‘terrorist’ threat. The rhetoric of interiority/exteriority that is enunciated by the frame within a frame reflects and constitutes sovereignty’s reliance on the notion of the state of exception in order to establish and consolidate itself. Just as, following Giorgio Agamben and others, the state of exception is at the heart of the power of the state, so is the embedded frame at the heart of the depiction of power in contemporary narratives. This analysis is based primarily on the television series 24 and on films based on novels by Tom Clancy.

This article proposes a political reading of certain aesthetic tendencies in contemporary action thrillers about “terrorism”. In particular, I examine the embedded screen, where the frame of one screen is enclosed within the frame of an outer screen. This is a prominent device in highly technologized thriller narratives concerning the pursuit of “terrorists” by counterterrorist agencies, such as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in Patriot Games (Phillip Noyce, 1992) or the Counter-Terrorist Unit (CTU) in the television series 24 (Fox Network 2001-). I propose that the rhetorical effect of the embedded screen as it appears in these narratives is to establish a political norm, thereby sanctioning certain political acts. It does this by indicating that, in contrast to the full screen, an embedded zone exists in a state of exception. This embedded screen offers us a manifestation, therefore, of the political situation where sovereignty or political authority is established and consolidated in the act of declaring a state of exception (also known, depending on the jurisdiction and circumstances, as martial law, state of emergency, state of siege, etc.). The description of certain types of violence (such as “terrorism”) as deserving special treatment by the forces of law and order is familiar both in the real world (as in the contemporary “War on Terror”) and in screen narratives concerning “terrorism”. In the following, several political science concepts are introduced in some detail before the film/television analysis proper, which attempts to show how these concepts are manifested in Patriot Games, 24 and other narratives.

Embeddedness

At its simplest, “embeddedness” is the appearance of one image inside the frame of another. There does not necessarily have to be a similarity between the two images for us to use the term, though it is often the case that there is a resemblance of type, proportion or dimension. Where there is a distinct similarity between the two images in question, we usually speak of mise en abyme, which refers originally to an element of a heraldic device which is itself a facsimile of the entire device in which it is embedded. When applied in non-heraldic contexts such as painting (e.g. Velázquez’ Las Meninas) or film, the peculiar power of this type of embeddedness is realised by extrapolating its logic on either an increasing or a decreasing scale, or on both scales simultaneously. For example, if an image contains itself in miniature, then the smaller version must also contain that image, which in turn must also contain the image, and so on – a process of extrapolation that can have dizzying consequences (abyme means “abyss”). The same effect is achieved if a given image is regarded as already being part of a greater whole, which can be perceived only by zooming out, so to speak.

In 24 , there are multiple instances of screens embedded in the screen that we are watching. The key characteristic of 24 is simultaneity; the countdown of the clock of each episode is supposed to correspond with the passage of time as experienced by the viewer. Several narrative strands run simultaneously throughout each episode, but the links between the various plot lines are not achieved by standard parallel editing, such as that developed in The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915), where the audience is presented with alternating scenes from separate fields of action, such as the chasing posse and the pursued man. Rather, 24 accentuates the simultaneity effect by tiling the screen with two or more of the various fields of action that are currently in play. The tiling effect is reminiscent of the manipulation of windows on a computer screen-desktop and is therefore in keeping with the highly-technologized aesthetic of the show; in this way the television screen suggests that it may be more than the one-way medium it is conventionally taken to be, intimating instead the interactive possibilities of computers and of digital television.[1]

I suggest that in relation to scenes such as that illustrated below, the term “embeddedness” is more useful than the commonly used phrase “split-screen” because it describes both how the screen has been split and how any given image can also contain further framed screens within itself (as is the case at top left). Regarding all of the various frames in this image as instances of embeddedness emphasises the fact that what we usually regard simply as split-screen is in fact the emplacement of multiple frames inside the main frame of the primary screen. This emphasis draws attention more effectively, in my opinion, to the fact that the establishment of any frame both sets the ground for an act of enunciation to be made and is itself an enunciation. The importance of this will become more apparent later when we examine the political theory that argues that power establishes itself through acts of decisive enunciation.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

The Embedded Screen and the State of Exception: Counterterrorist Narratives and the War on Terror

by Cormac Deane

Refractory (Melbourne University, Australia)

Abstract: The embedded screen is a key feature of contemporary film and television texts featuring ‘terrorism’. Recurring chronotopes in these narratives, such as the control room and television news programmes, present us with frames within frames that have two complementary functions. First, embedded frames enact circular modes of logic, such as tautology and autology, which are crucial in the creation of a coherent notion of ‘terrorism’. Second, embedded frames are the screen-manifestation of the legal concept of the state of exception, which must be invoked so that the forces of law and order can take extraordinary measures in the face of a ‘terrorist’ threat. The rhetoric of interiority/exteriority that is enunciated by the frame within a frame reflects and constitutes sovereignty’s reliance on the notion of the state of exception in order to establish and consolidate itself. Just as, following Giorgio Agamben and others, the state of exception is at the heart of the power of the state, so is the embedded frame at the heart of the depiction of power in contemporary narratives. This analysis is based primarily on the television series 24 and on films based on novels by Tom Clancy.

This article proposes a political reading of certain aesthetic tendencies in contemporary action thrillers about “terrorism”. In particular, I examine the embedded screen, where the frame of one screen is enclosed within the frame of an outer screen. This is a prominent device in highly technologized thriller narratives concerning the pursuit of “terrorists” by counterterrorist agencies, such as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in Patriot Games (Phillip Noyce, 1992) or the Counter-Terrorist Unit (CTU) in the television series 24 (Fox Network 2001-). I propose that the rhetorical effect of the embedded screen as it appears in these narratives is to establish a political norm, thereby sanctioning certain political acts. It does this by indicating that, in contrast to the full screen, an embedded zone exists in a state of exception. This embedded screen offers us a manifestation, therefore, of the political situation where sovereignty or political authority is established and consolidated in the act of declaring a state of exception (also known, depending on the jurisdiction and circumstances, as martial law, state of emergency, state of siege, etc.). The description of certain types of violence (such as “terrorism”) as deserving special treatment by the forces of law and order is familiar both in the real world (as in the contemporary “War on Terror”) and in screen narratives concerning “terrorism”. In the following, several political science concepts are introduced in some detail before the film/television analysis proper, which attempts to show how these concepts are manifested in Patriot Games, 24 and other narratives.

Embeddedness

At its simplest, “embeddedness” is the appearance of one image inside the frame of another. There does not necessarily have to be a similarity between the two images for us to use the term, though it is often the case that there is a resemblance of type, proportion or dimension. Where there is a distinct similarity between the two images in question, we usually speak of mise en abyme, which refers originally to an element of a heraldic device which is itself a facsimile of the entire device in which it is embedded. When applied in non-heraldic contexts such as painting (e.g. Velázquez’ Las Meninas) or film, the peculiar power of this type of embeddedness is realised by extrapolating its logic on either an increasing or a decreasing scale, or on both scales simultaneously. For example, if an image contains itself in miniature, then the smaller version must also contain that image, which in turn must also contain the image, and so on – a process of extrapolation that can have dizzying consequences (abyme means “abyss”). The same effect is achieved if a given image is regarded as already being part of a greater whole, which can be perceived only by zooming out, so to speak.

In 24 , there are multiple instances of screens embedded in the screen that we are watching. The key characteristic of 24 is simultaneity; the countdown of the clock of each episode is supposed to correspond with the passage of time as experienced by the viewer. Several narrative strands run simultaneously throughout each episode, but the links between the various plot lines are not achieved by standard parallel editing, such as that developed in The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915), where the audience is presented with alternating scenes from separate fields of action, such as the chasing posse and the pursued man. Rather, 24 accentuates the simultaneity effect by tiling the screen with two or more of the various fields of action that are currently in play. The tiling effect is reminiscent of the manipulation of windows on a computer screen-desktop and is therefore in keeping with the highly-technologized aesthetic of the show; in this way the television screen suggests that it may be more than the one-way medium it is conventionally taken to be, intimating instead the interactive possibilities of computers and of digital television.[1]

I suggest that in relation to scenes such as that illustrated below, the term “embeddedness” is more useful than the commonly used phrase “split-screen” because it describes both how the screen has been split and how any given image can also contain further framed screens within itself (as is the case at top left). Regarding all of the various frames in this image as instances of embeddedness emphasises the fact that what we usually regard simply as split-screen is in fact the emplacement of multiple frames inside the main frame of the primary screen. This emphasis draws attention more effectively, in my opinion, to the fact that the establishment of any frame both sets the ground for an act of enunciation to be made and is itself an enunciation. The importance of this will become more apparent later when we examine the political theory that argues that power establishes itself through acts of decisive enunciation.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

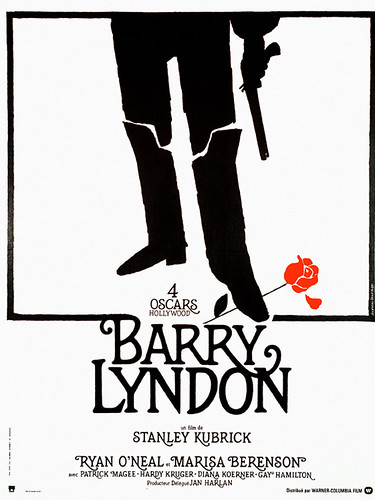

Craig Phillips: French New Wave (A Primer)

French New Wave

by Craig Phillips

Green Cine

An artistic movement whose influence on film has been as profound and enduring as that of surrealism or cubism on painting, the French New Wave (or Le Nouvelle Vague) made its first splashes as a movement shot through with youthful exuberance and a brisk reinvigoration of the filmmaking process. Most agree that the French New Wave was at its peak between 1958 and 1964, but it continued to ripple on afterwards, with many of the tendencies and styles introduced by the movement still in practice today.

Immediately after World War II, France, like most of the rest of Europe, was in a major state of flux and upheaval; in film, it was a period of great transition. During the German Occupation (1940-45), many of France's greatest directors (René Clair, Jean Renoir, Jacques Feyder among them) had gone into exile. A new generation of filmmakers emerged - but wait! This isn't the New Wave, relax, we're not there yet - and chief among these was René Clément, who had co-directed the classic surrealist fairy tale Beauty and the Beast with playwright Jean Cocteau, and then in the 1950s, furthered his reputation with Forbidden Games. After the traumatic experience of war, a generation gap of sorts emerged between the more "old school" French classic filmmakers and a younger generation who set out to do things differently.

In the 50s, a collective of intellectual French film critics, led by André Bazin and Jacques Donial-Valcroze, formed the groundbreaking journal of film criticism Cahiers du Cinema. They, in turn, had been influenced by the writings of French film critic Alexandre Astruc, who had argued for breaking away from the "tyranny of narrative" in favor of a new form of film (and sound) language. The Cahiers critics gathered by Bazin and Doniol-Valcroze were all young cinephiles who had grown up in the post-war years watching mostly great American films that had not been available in France during the Occupation.

Cahiers had two guiding principles:

1) A rejection of classical montage-style filmmaking (favored by studios up to that time) in favor of: mise-en-scene, or, literally, "placing in the scene" (favoring the reality of what is filmed over manipulation via editing), the long take, and deep composition; and

2) A conviction that the best films are a personal artistic expression and should bear a stamp of personal authorship, much as great works of literature bear the stamp of the writer. This latter tenet would be dubbed by American film critic Andrew Sarris the "auteur (author) theory."

This philosophy, not surprisingly, led to the rejection of more traditional French commercial cinema (Clair, Clement, Henri-Georges Clouzout, Marc Allegret, among others), and instead embraced directors - both French and American - whose personal signature could be read in their films. The French directors the Cahiers critics endorsed included Jean Vigo, Renoir, Robert Bresson and Marcel Ophüls; while the Americans on their list of favorites included John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang, Nicholas Ray and Orson Welles, indisputed masters, all. There were also a few surprising, even head-scratching favorites, including Jerry Lewis (thus beginning the stereotype about France's Lewis obsession) and Roger Corman.

Many of the French New Wave's favorite conventions actually sprang not only from artistic tenets but from necessity and circumstance. These critics-turned-filmmakers knew a great deal about film history and theory but a lot less about film production. In addition, they were, especially at the start, working on low budgets. Thus, they often improvised with what schedules and materials they could afford. Out of all this came a group of conventions that were consistently used in the majority of French New Wave films (similar to, but less encapsulated than, Denmark's Dogme 95 "manifesto"), including:

# Jump cuts: a non-naturalistic edit, usually a section of a continuous shot that is removed unexpectedly, illogically

# Shooting on location

# Natural lighting

# Improvised dialogue and plotting

# Direct sound recording

# Long takes

Many of these conventions are commonplace today, but back in the late 1950s and early 1960s, this was all very groundbreaking. Jump cuts were used as much to cover mistakes as they were an artistic convention. Jean-Luc Godard certainly appreciated the dislocating feel a jump cut conveyed, but let's remember - here was a film critic-turned-first-time director who was also using inexperienced actors and crew, and shooting, at least at first, on a shoestring budget. Therefore, as Nixon once said, mistakes were made. Today when jump cuts are used they even feel more like a pretentious artifice.

Many will argue (and rather pointlessly when it comes down to it) which film was the first of the French New Wave; officially, the first work out of this group wasn't a feature at all, but rather, short films produced in 1956 and 57, including Jacques Rivette's Le coup du berger (Fool's Mate) and François Truffaut's Les Mistons (The Mischief Makers). Some point to Claude Chabrol's Le beau Serge (1958) as the first feature success of the New Wave. He shot the low budget film on location and used the money raised from its release to make Les cousins; with its depiction of two student cousins, one good, one bad, it's the first Chabrol film to contain his uniquely sardonic view of the world. Les cousins is particularly interesting when looking at the typical qualities of early French New Wave works, because of its long, memorable party sequence which climaxes in a very cruel joke.

To Read the Rest of the Primer

by Craig Phillips

Green Cine

An artistic movement whose influence on film has been as profound and enduring as that of surrealism or cubism on painting, the French New Wave (or Le Nouvelle Vague) made its first splashes as a movement shot through with youthful exuberance and a brisk reinvigoration of the filmmaking process. Most agree that the French New Wave was at its peak between 1958 and 1964, but it continued to ripple on afterwards, with many of the tendencies and styles introduced by the movement still in practice today.

Immediately after World War II, France, like most of the rest of Europe, was in a major state of flux and upheaval; in film, it was a period of great transition. During the German Occupation (1940-45), many of France's greatest directors (René Clair, Jean Renoir, Jacques Feyder among them) had gone into exile. A new generation of filmmakers emerged - but wait! This isn't the New Wave, relax, we're not there yet - and chief among these was René Clément, who had co-directed the classic surrealist fairy tale Beauty and the Beast with playwright Jean Cocteau, and then in the 1950s, furthered his reputation with Forbidden Games. After the traumatic experience of war, a generation gap of sorts emerged between the more "old school" French classic filmmakers and a younger generation who set out to do things differently.

In the 50s, a collective of intellectual French film critics, led by André Bazin and Jacques Donial-Valcroze, formed the groundbreaking journal of film criticism Cahiers du Cinema. They, in turn, had been influenced by the writings of French film critic Alexandre Astruc, who had argued for breaking away from the "tyranny of narrative" in favor of a new form of film (and sound) language. The Cahiers critics gathered by Bazin and Doniol-Valcroze were all young cinephiles who had grown up in the post-war years watching mostly great American films that had not been available in France during the Occupation.

Cahiers had two guiding principles:

1) A rejection of classical montage-style filmmaking (favored by studios up to that time) in favor of: mise-en-scene, or, literally, "placing in the scene" (favoring the reality of what is filmed over manipulation via editing), the long take, and deep composition; and

2) A conviction that the best films are a personal artistic expression and should bear a stamp of personal authorship, much as great works of literature bear the stamp of the writer. This latter tenet would be dubbed by American film critic Andrew Sarris the "auteur (author) theory."

This philosophy, not surprisingly, led to the rejection of more traditional French commercial cinema (Clair, Clement, Henri-Georges Clouzout, Marc Allegret, among others), and instead embraced directors - both French and American - whose personal signature could be read in their films. The French directors the Cahiers critics endorsed included Jean Vigo, Renoir, Robert Bresson and Marcel Ophüls; while the Americans on their list of favorites included John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang, Nicholas Ray and Orson Welles, indisputed masters, all. There were also a few surprising, even head-scratching favorites, including Jerry Lewis (thus beginning the stereotype about France's Lewis obsession) and Roger Corman.

Many of the French New Wave's favorite conventions actually sprang not only from artistic tenets but from necessity and circumstance. These critics-turned-filmmakers knew a great deal about film history and theory but a lot less about film production. In addition, they were, especially at the start, working on low budgets. Thus, they often improvised with what schedules and materials they could afford. Out of all this came a group of conventions that were consistently used in the majority of French New Wave films (similar to, but less encapsulated than, Denmark's Dogme 95 "manifesto"), including:

# Jump cuts: a non-naturalistic edit, usually a section of a continuous shot that is removed unexpectedly, illogically

# Shooting on location

# Natural lighting

# Improvised dialogue and plotting

# Direct sound recording

# Long takes

Many of these conventions are commonplace today, but back in the late 1950s and early 1960s, this was all very groundbreaking. Jump cuts were used as much to cover mistakes as they were an artistic convention. Jean-Luc Godard certainly appreciated the dislocating feel a jump cut conveyed, but let's remember - here was a film critic-turned-first-time director who was also using inexperienced actors and crew, and shooting, at least at first, on a shoestring budget. Therefore, as Nixon once said, mistakes were made. Today when jump cuts are used they even feel more like a pretentious artifice.

Many will argue (and rather pointlessly when it comes down to it) which film was the first of the French New Wave; officially, the first work out of this group wasn't a feature at all, but rather, short films produced in 1956 and 57, including Jacques Rivette's Le coup du berger (Fool's Mate) and François Truffaut's Les Mistons (The Mischief Makers). Some point to Claude Chabrol's Le beau Serge (1958) as the first feature success of the New Wave. He shot the low budget film on location and used the money raised from its release to make Les cousins; with its depiction of two student cousins, one good, one bad, it's the first Chabrol film to contain his uniquely sardonic view of the world. Les cousins is particularly interesting when looking at the typical qualities of early French New Wave works, because of its long, memorable party sequence which climaxes in a very cruel joke.

To Read the Rest of the Primer

Monday, February 23, 2009

David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson: Doing Film History

Doing Film History

by David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson

David Bordwell's Website on Cinema

Nearly everybody loves movies. We aren’t surprised that people rush to see the latest hit or rent a cult favorite from the video store. But there are some people who seek out old movies. And among those fans there’s a still smaller group studying them.

Let’s call “old movies” anything older than twenty years. This of course creates a moving target. Baby boomers like us don’t really consider The Godfather or M*A*S*H to be old movies, but many twentysomethings today will probably consider Pulp Fiction (1994) to be old — maybe because they saw it when they were in their teens. Our twenty-year cutoff is arbitrary, but in many cases that won’t matter. Everybody agrees that La Grande Illusion from 1935 is an old movie, though it still seems fresh and vital.

Now for the real question. Why would anyone be interested in watching and studying old movies?

Ask a film historian, professional or amateur, and you’ll get a variety of answers. For one thing, old films provide the same sorts of insights that we get from watching contemporary movies. Some offer intense artistic experiences or penetrating visions of human life in other times and places. Some are documents of everyday existence or of extraordinary historical events that continue to reverberate in our times. Still other old movies are resolutely strange. They resist assimilation to our current habits of thought. They force us to acknowledge that films can be radically different from what we are used to. They ask us to adjust our field of view to accommodate what was, astonishingly, taken for granted by people in earlier eras.

Another reason to study old movies is that film history encompasses more than just films. By studying how films were made and received, we discover how creators and audiences responded to their moment in history. By searching for social and cultural influences on films, we understand better the ways in which films bear the traces of the societies that made and consumed them. Film history opens up a range of important issues in politics, culture, and the arts—both “high” and “popular.”

Yet another answer to our question is this: Studying old movies and the times in which they were made is intrinsically fun. As a relatively new field of academic research (no more than sixty years old), film history has the excitement of a young discipline. Over the past few decades, many lost films have been recovered, little-known genres explored, and neglected filmmakers reevaluated. Ambitious retrospectives have revealed entire national cinemas that had been largely ignored. Even television, with some cable stations devoted wholly to the cinema of the past, brings into our living rooms movies that were previously rare and little-known.

And much more remains to be discovered. There are more old movies than new ones and, hence, many more chances for fascinating viewing experiences.

We think that studying film history is so interesting and important that during the late 1980s we began to write a book surveying the field. The first edition of Film History: An Introduction appeared in 1994, the second in 2003, and the third will be published in spring of 2009. In this book we have tried to introduce the history of cinema as it is conceived, written, and taught by its most accomplished scholars. But the book isn’t a distillation of all film history. We have had to rule out certain types of cinema that are important, most notably educational, industrial, scientific, and pornographic films. We limit our scope to theatrical fiction films, documentary films, experimental or avant-garde filmmaking, and animation—realms of filmmaking that are most frequently studied in college courses.

Researchers are fond of saying that there is no film history, only film histories. For some, this means that there can be no intelligible, coherent “grand narrative” that puts all the facts into place. The history of avant-garde film does not fit neatly into the history of color technology or the development of the Western or the life of John Ford. For others, film history means that historians work from various perspectives and with different interests and purposes.

We agree with both points. There is no Big Story of Film History that accounts for all events, causes, and consequences. And the variety of historical approaches guarantees that historians will draw diverse conclusions.

We also think that research into film history involves asking a series of questions and searching for evidence in order to answer them in the course of an argument. When historians focus on different questions, turn up different evidence, and formulate different explanations, we derive not a single history but a diverse set of historical arguments.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson

David Bordwell's Website on Cinema

Nearly everybody loves movies. We aren’t surprised that people rush to see the latest hit or rent a cult favorite from the video store. But there are some people who seek out old movies. And among those fans there’s a still smaller group studying them.

Let’s call “old movies” anything older than twenty years. This of course creates a moving target. Baby boomers like us don’t really consider The Godfather or M*A*S*H to be old movies, but many twentysomethings today will probably consider Pulp Fiction (1994) to be old — maybe because they saw it when they were in their teens. Our twenty-year cutoff is arbitrary, but in many cases that won’t matter. Everybody agrees that La Grande Illusion from 1935 is an old movie, though it still seems fresh and vital.

Now for the real question. Why would anyone be interested in watching and studying old movies?

Ask a film historian, professional or amateur, and you’ll get a variety of answers. For one thing, old films provide the same sorts of insights that we get from watching contemporary movies. Some offer intense artistic experiences or penetrating visions of human life in other times and places. Some are documents of everyday existence or of extraordinary historical events that continue to reverberate in our times. Still other old movies are resolutely strange. They resist assimilation to our current habits of thought. They force us to acknowledge that films can be radically different from what we are used to. They ask us to adjust our field of view to accommodate what was, astonishingly, taken for granted by people in earlier eras.

Another reason to study old movies is that film history encompasses more than just films. By studying how films were made and received, we discover how creators and audiences responded to their moment in history. By searching for social and cultural influences on films, we understand better the ways in which films bear the traces of the societies that made and consumed them. Film history opens up a range of important issues in politics, culture, and the arts—both “high” and “popular.”

Yet another answer to our question is this: Studying old movies and the times in which they were made is intrinsically fun. As a relatively new field of academic research (no more than sixty years old), film history has the excitement of a young discipline. Over the past few decades, many lost films have been recovered, little-known genres explored, and neglected filmmakers reevaluated. Ambitious retrospectives have revealed entire national cinemas that had been largely ignored. Even television, with some cable stations devoted wholly to the cinema of the past, brings into our living rooms movies that were previously rare and little-known.

And much more remains to be discovered. There are more old movies than new ones and, hence, many more chances for fascinating viewing experiences.

We think that studying film history is so interesting and important that during the late 1980s we began to write a book surveying the field. The first edition of Film History: An Introduction appeared in 1994, the second in 2003, and the third will be published in spring of 2009. In this book we have tried to introduce the history of cinema as it is conceived, written, and taught by its most accomplished scholars. But the book isn’t a distillation of all film history. We have had to rule out certain types of cinema that are important, most notably educational, industrial, scientific, and pornographic films. We limit our scope to theatrical fiction films, documentary films, experimental or avant-garde filmmaking, and animation—realms of filmmaking that are most frequently studied in college courses.

Researchers are fond of saying that there is no film history, only film histories. For some, this means that there can be no intelligible, coherent “grand narrative” that puts all the facts into place. The history of avant-garde film does not fit neatly into the history of color technology or the development of the Western or the life of John Ford. For others, film history means that historians work from various perspectives and with different interests and purposes.

We agree with both points. There is no Big Story of Film History that accounts for all events, causes, and consequences. And the variety of historical approaches guarantees that historians will draw diverse conclusions.

We also think that research into film history involves asking a series of questions and searching for evidence in order to answer them in the course of an argument. When historians focus on different questions, turn up different evidence, and formulate different explanations, we derive not a single history but a diverse set of historical arguments.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Pete Kozachik Cinematographer of Coraline: 2 Worlds in 3 Dimensions

(Also check out David Bordwell's appreciation of and commentary on Pete Kozachik's article on the techniques used in this film: Coraline Cornered. Laura asked me to watch this film with her and I was blown away by the innovative imagery. Highly recommended!)

2 Worlds in 3 Dimensions

Pete Kozachik, ASC details his approach to the 3-D digital stop-motion feature Coraline, whose heroine discovers a sinister world behind the walls of her new home.

American Cinematographer (The American Society of Cinematographers)

Exciting events tend to happen as soon as conditions are right, and Henry Selick’s stop-motion feature Coraline, based on Neil Gaiman’s supernatural novella, rides in on a host of new innovations, including advanced machine-vision cameras and the emergence of practical 3-D. Most instrumental was the birth of Laika Entertainment, Phil Knight’s startup animation company in Oregon, fresh and eager to try something new.

I made it a priority to line up talented and experienced cameramen early. Leading their three-man units were cinematographers John Ashlee, Paul Gentry, Mark Stewart, Peter Sorg, Chris Peterson, Brian Van’t Hul, Peter Williams and Frank Passingham. Most of the camera assistants and electricians had shooting experience of their own, making the camera department pretty well bulletproof. With more than 55 setups working at the same time, we needed guys that were quick, organized and versatile.

From the beginning, we knew the two worlds Coraline inhabits — the drab “Real World” and the fantastic “Other World” — would be distorted mirror images of each other, as different in tone as Kansas and Oz. Camera and art departments would create the differences, keeping the emphasis on Coraline’s feelings. Among the closest film references for the supernatural Other World were the exaggerated color schemes in Amélie, which we used when the Other Mother is enticing Coraline to stay with her. The Shining and The Orphanage provided good reference for interiors when things go awry.

Image banks such as flickr.com were a good source for reference pics, and including those shots in my lighting and camera notes helped jump-start crews on new sequences. Artist Tadahiro Uesugi supplied a valuable influence for the show; his work has a graphic simplicity, like fashion art from the Fifties, with minimal modeling but an awareness of light. It helped in spirit to guide us away from excess gingerbread, which is typical in both art and lighting for stop-motion animation. Our film has plenty of interesting things to look at, but we did our best to make every bit of eye candy contribute to the main story. Uesugi’s handheld stylus gives lines a slightly wavy edge, which the art department used to weave more life into architecture.

To Read the rest of the article

2 Worlds in 3 Dimensions

Pete Kozachik, ASC details his approach to the 3-D digital stop-motion feature Coraline, whose heroine discovers a sinister world behind the walls of her new home.

American Cinematographer (The American Society of Cinematographers)

Exciting events tend to happen as soon as conditions are right, and Henry Selick’s stop-motion feature Coraline, based on Neil Gaiman’s supernatural novella, rides in on a host of new innovations, including advanced machine-vision cameras and the emergence of practical 3-D. Most instrumental was the birth of Laika Entertainment, Phil Knight’s startup animation company in Oregon, fresh and eager to try something new.

I made it a priority to line up talented and experienced cameramen early. Leading their three-man units were cinematographers John Ashlee, Paul Gentry, Mark Stewart, Peter Sorg, Chris Peterson, Brian Van’t Hul, Peter Williams and Frank Passingham. Most of the camera assistants and electricians had shooting experience of their own, making the camera department pretty well bulletproof. With more than 55 setups working at the same time, we needed guys that were quick, organized and versatile.

From the beginning, we knew the two worlds Coraline inhabits — the drab “Real World” and the fantastic “Other World” — would be distorted mirror images of each other, as different in tone as Kansas and Oz. Camera and art departments would create the differences, keeping the emphasis on Coraline’s feelings. Among the closest film references for the supernatural Other World were the exaggerated color schemes in Amélie, which we used when the Other Mother is enticing Coraline to stay with her. The Shining and The Orphanage provided good reference for interiors when things go awry.