"My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel--it is, above all, to make you see." -- Joseph Conrad (1897)

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Lorraine Mortimer: Something Against Nature - Sweet Movie, 4, and Disgust

Something Against Nature: Sweet Movie, 4, and Disgust

by Lorraine Mortimer

Senses of Cinema

...

Makavejev shared Wilhelm Reich’s valuing of autonomy, not as an abstract ideal, but as a somatic-emotional experience—that of setting one’s own limits in relation to others. Like Reich, he was convinced of the dangers of servility, of raising human beings who do not know their own nature, and who can become prey to the call of tyrants with the promise of wholeness, happiness and empowerment. John Stuart Mill articulated something of this idea long ago, when he wrote of people from the highest to the lowest classes of society, who live “as under the eye of a hostile and dreaded censorship”, until “by dint of not following their own nature, they have no nature to follow: their human capacities are withered and starved.” (17) These capacities, often less-than-heroic, and by no means all attractive, are exercised and performed in Sweet Movie, where physiological revolt is acted out, provoked, and experienced, one way or another, by the viewer him- or herself. The commune sequences, writes Cavell,

Cavell’s ‘innocence’ here, like that of the poet, William Blake, is not related to ignorance or denial. It is intense, fulsome and complex, opposed to a cynical and sour experience. “The road to excess leads to the palace of wisdom”, was one of Blake’s proverbs from ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’. Called ‘mad’ by some of his contemporary artists and political radicals, he might have envisioned such scenes as we have in this film in some of his wildest hallucinations. Said Cavell, wisely:

Sweet Movie [is] in effect the most concentrated work I know that follows out the idea that the way to assess the state of the world is to find out how it tastes (a sense modality not notably stressed by orthodox epistemologists but rather consigned to a corner of aesthetics)—which means both to find out how it tastes to you and how it tastes you, for example, to find out whether you and the world are disgusting to one another…

The film attempts to extract hope…from the very fact that we are capable of genuine disgust at the world; that our revoltedness is a chance for a cleansing revulsion; that we may purge ourselves by living rather than by killing, willing to visit hell if that is the direction to something beyond purgatory; that the fight for freedom continues to originate in the demands of our instincts, the chaotic cry of our nature, our cry to have a nature. It is a work powerful enough to encourage us to see again that the tyrant’s power continues to require our complicitous tyranny over ourselves. (19)

Early in the commune sequence, before Momma Communa (outrageously) suckled Miss World, when she was feeding her own baby, we watched something not often seen in (civilised) public spaces. The camera didn’t cut away from the baby withdrawing itself from her nipple, which in its elongated shape, looked something like a dagger—or a penis. In a way, the act of nourishment and nurture can have a discomforting edge to it, a seeming ‘indecency’, as if we are exposed to what Mary Douglas called “matter out of place.” (20) In nature as in life, nothing is pure. Once we let natural vitality into our picture, we must also let in decay; when we admit the reality of birth and death. The ‘theatre’ of the commune scenes doesn’t let us escape the realities of bodily functions, the breakdown of boundaries between solids and liquids, inside and outside, cultural and biological. And the performance is unapologetic and even aggressive, certainly on a first viewing, when we are unprepared and often overwhelmed. For members of the film’s audience, Cavell’s “cleansing revulsion”, the purging “by living rather than by killing” are probably far harder for us to take because we are not actual participants. There is perhaps a feeling of helplessly watching a difficult birth. The shaved heads and nude bodies of the participants perhaps conjure up Auschwitz, especially in this film where we have watched unearthings of victims of a war massacre. But more than this, in this spectacle that we are (as if) locked into, the regressing participants clearly don’t become babies but appear as infantile, less than attractive, adults. As their bodies seem to take on their own wills, with their uncoordinated movements, and lack of boundaries and protocols for bodily substances, more than adults undertaking a certain kind of liberation, they conjure up the disturbed and the sick, the dying—humans who are losing ordinary ‘civil’ controls and proprieties they struggle to keep with age and illness. Their carnal humus is revealed, the evidence that they, and we, are in the end, degradable matter.

...

To Read the Entire Essay

by Lorraine Mortimer

Senses of Cinema

...

Makavejev shared Wilhelm Reich’s valuing of autonomy, not as an abstract ideal, but as a somatic-emotional experience—that of setting one’s own limits in relation to others. Like Reich, he was convinced of the dangers of servility, of raising human beings who do not know their own nature, and who can become prey to the call of tyrants with the promise of wholeness, happiness and empowerment. John Stuart Mill articulated something of this idea long ago, when he wrote of people from the highest to the lowest classes of society, who live “as under the eye of a hostile and dreaded censorship”, until “by dint of not following their own nature, they have no nature to follow: their human capacities are withered and starved.” (17) These capacities, often less-than-heroic, and by no means all attractive, are exercised and performed in Sweet Movie, where physiological revolt is acted out, provoked, and experienced, one way or another, by the viewer him- or herself. The commune sequences, writes Cavell,

are, among other things, revolting. Placed in general adjacency with the sequence of the Katyn massacre, which is also revolting, we are asked to ask ourselves what we are revolted by… If rotting corpses make us want to vomit, why at the same time do live bodies insisting on their vitality? But the members of the commune themselves display images of revulsion, as if to vomit up the snakes and swords and fire the world forces down our throats. It is on this understanding that the sequence strikes me as one of innocence, or of a quest for innocence—the exact reverse of the unredeemable acts of tyrants, under whatever banner. (18)

Cavell’s ‘innocence’ here, like that of the poet, William Blake, is not related to ignorance or denial. It is intense, fulsome and complex, opposed to a cynical and sour experience. “The road to excess leads to the palace of wisdom”, was one of Blake’s proverbs from ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’. Called ‘mad’ by some of his contemporary artists and political radicals, he might have envisioned such scenes as we have in this film in some of his wildest hallucinations. Said Cavell, wisely:

Sweet Movie [is] in effect the most concentrated work I know that follows out the idea that the way to assess the state of the world is to find out how it tastes (a sense modality not notably stressed by orthodox epistemologists but rather consigned to a corner of aesthetics)—which means both to find out how it tastes to you and how it tastes you, for example, to find out whether you and the world are disgusting to one another…

The film attempts to extract hope…from the very fact that we are capable of genuine disgust at the world; that our revoltedness is a chance for a cleansing revulsion; that we may purge ourselves by living rather than by killing, willing to visit hell if that is the direction to something beyond purgatory; that the fight for freedom continues to originate in the demands of our instincts, the chaotic cry of our nature, our cry to have a nature. It is a work powerful enough to encourage us to see again that the tyrant’s power continues to require our complicitous tyranny over ourselves. (19)

Early in the commune sequence, before Momma Communa (outrageously) suckled Miss World, when she was feeding her own baby, we watched something not often seen in (civilised) public spaces. The camera didn’t cut away from the baby withdrawing itself from her nipple, which in its elongated shape, looked something like a dagger—or a penis. In a way, the act of nourishment and nurture can have a discomforting edge to it, a seeming ‘indecency’, as if we are exposed to what Mary Douglas called “matter out of place.” (20) In nature as in life, nothing is pure. Once we let natural vitality into our picture, we must also let in decay; when we admit the reality of birth and death. The ‘theatre’ of the commune scenes doesn’t let us escape the realities of bodily functions, the breakdown of boundaries between solids and liquids, inside and outside, cultural and biological. And the performance is unapologetic and even aggressive, certainly on a first viewing, when we are unprepared and often overwhelmed. For members of the film’s audience, Cavell’s “cleansing revulsion”, the purging “by living rather than by killing” are probably far harder for us to take because we are not actual participants. There is perhaps a feeling of helplessly watching a difficult birth. The shaved heads and nude bodies of the participants perhaps conjure up Auschwitz, especially in this film where we have watched unearthings of victims of a war massacre. But more than this, in this spectacle that we are (as if) locked into, the regressing participants clearly don’t become babies but appear as infantile, less than attractive, adults. As their bodies seem to take on their own wills, with their uncoordinated movements, and lack of boundaries and protocols for bodily substances, more than adults undertaking a certain kind of liberation, they conjure up the disturbed and the sick, the dying—humans who are losing ordinary ‘civil’ controls and proprieties they struggle to keep with age and illness. Their carnal humus is revealed, the evidence that they, and we, are in the end, degradable matter.

...

To Read the Entire Essay

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

Greta Christina: Wealthy, Handsome, Strong, Packing Endless Hard-Ons - The Impossible Ideals Men Are Expected to Meet

Wealthy, Handsome, Strong, Packing Endless Hard-Ons: The Impossible Ideals Men Are Expected to Meet

By Greta Christina

AlterNet

You've almost certainly heard feminist rants about impossible cultural ideals of femininity: how standards of femininity are so narrow and rigid they're literally unattainable; how, to avoid being seen as unfeminine, women are expected to navigate an increasingly narrow window between slut and prude, between capable and docile, between moral enforcer and empathetic helpmeet.

Here's what you may not know: It works that way for men as well.

A recent article about male fitness models has made me vividly conscious of how the expectations of masculinity aren't just rigid or narrow. They are impossible. They are, quite literally, unattainable.

And while this unattainability can tie men into knots, I think -- in a weird paradox -- it can also offer a glimmer of hope.

The article in question is about the hellish, dangerous, illness-inducing routines that male fitness models regularly go through to forge their bodies into an attractive photograph of the masculine ideal. According to journalist Peta Bee in the Express UK (the article was originally published in the Sunday Times [London], but they put it behind a paywall), in order to make their bodies more photogenic and more in keeping with the masculine "fitness" ideal, top male fitness models routinely put themselves through an extreme regimen in the days and weeks before a photo shoot. Not a regimen of intense exercise and rigorously healthy diet, mind you... but a regimen that involves starvation, dehydration, excessive consumption of alcohol and sugar right before a shoot, and more.

This routine is entirely unrelated to any concept of "fitness." In fact, it leaves the models in a state of serious hypoglycemia: dizzy, exhausted, disoriented, and (ironically) unable to exercise, and indeed barely able to walk. But the routine makes their muscles look big, and tightens their skin to make their muscles "pop" on camera. And even then, the magazines use lighting tricks, posture tricks, flat-out deceptions, even Photoshop, to exaggerate this illusion of masculinity even further.

On any sort of realistic irony meter, the concept of starved, dehydrated, dazed, weakened men being offered as models of fitness completely buries the needle. But this isn't about reality. The image being sold is clearly not one of "fitness" -- i.e. athletic ability and physical health. The image being sold is an exaggerated, idealized, impossible extreme of hyper-masculinity.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

By Greta Christina

AlterNet

You've almost certainly heard feminist rants about impossible cultural ideals of femininity: how standards of femininity are so narrow and rigid they're literally unattainable; how, to avoid being seen as unfeminine, women are expected to navigate an increasingly narrow window between slut and prude, between capable and docile, between moral enforcer and empathetic helpmeet.

Here's what you may not know: It works that way for men as well.

A recent article about male fitness models has made me vividly conscious of how the expectations of masculinity aren't just rigid or narrow. They are impossible. They are, quite literally, unattainable.

And while this unattainability can tie men into knots, I think -- in a weird paradox -- it can also offer a glimmer of hope.

The article in question is about the hellish, dangerous, illness-inducing routines that male fitness models regularly go through to forge their bodies into an attractive photograph of the masculine ideal. According to journalist Peta Bee in the Express UK (the article was originally published in the Sunday Times [London], but they put it behind a paywall), in order to make their bodies more photogenic and more in keeping with the masculine "fitness" ideal, top male fitness models routinely put themselves through an extreme regimen in the days and weeks before a photo shoot. Not a regimen of intense exercise and rigorously healthy diet, mind you... but a regimen that involves starvation, dehydration, excessive consumption of alcohol and sugar right before a shoot, and more.

This routine is entirely unrelated to any concept of "fitness." In fact, it leaves the models in a state of serious hypoglycemia: dizzy, exhausted, disoriented, and (ironically) unable to exercise, and indeed barely able to walk. But the routine makes their muscles look big, and tightens their skin to make their muscles "pop" on camera. And even then, the magazines use lighting tricks, posture tricks, flat-out deceptions, even Photoshop, to exaggerate this illusion of masculinity even further.

On any sort of realistic irony meter, the concept of starved, dehydrated, dazed, weakened men being offered as models of fitness completely buries the needle. But this isn't about reality. The image being sold is clearly not one of "fitness" -- i.e. athletic ability and physical health. The image being sold is an exaggerated, idealized, impossible extreme of hyper-masculinity.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Eve Ensler: I Am an Emotional Creature

Eve Ensler: I Am an Emotional Creature

Commonwealth Club

FORA TV

Since creating her groundbreaking first work, The Vagina Monologues, Ensler and the performers she inspired have grown into nothing less than a global movement.

A best-selling author, award-winning playwright and anti-violence activist, Ensler has been the voice for women and girls across the globe for over a decade.

In this conversation with author Daniel Handler, she reveals the daily struggles faced by modern women around the world.

To Watch the Conversation

Commonwealth Club

FORA TV

Since creating her groundbreaking first work, The Vagina Monologues, Ensler and the performers she inspired have grown into nothing less than a global movement.

A best-selling author, award-winning playwright and anti-violence activist, Ensler has been the voice for women and girls across the globe for over a decade.

In this conversation with author Daniel Handler, she reveals the daily struggles faced by modern women around the world.

To Watch the Conversation

Saturday, June 25, 2011

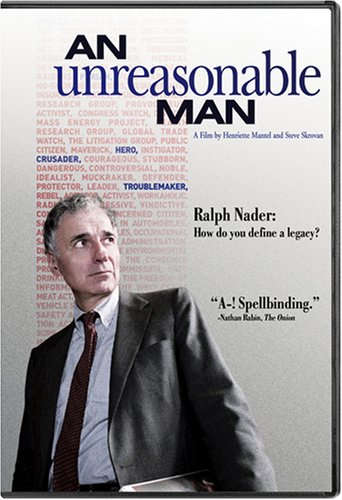

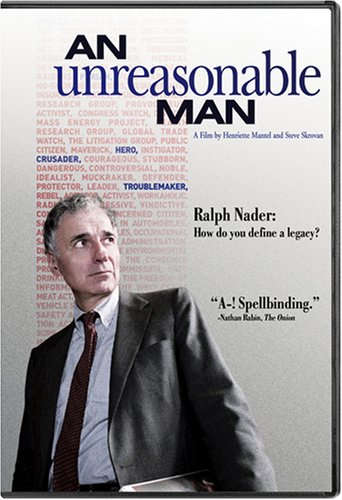

Film School: Henriette Mantel and Steve Skrovan -- An Unreasonable Man

AN UNREASONABLE MAN

Film School (KUCI)

Directors Henriette Mantel and Steve Skrovan discuss their documentary, An Unreasonable Man — the story of Ralph Nader, from wannabe presidential candidate to public pariah. In 1966, General Motors, the most powerful corporation in the world, sent private investigators to dig up dirt on an obscure thirty-two year old public interest lawyer named Ralph Nader, who had written a book critical of one of their cars, the Corvair. The scandal that ensued after the smear campaign was revealed launched Ralph Nader into national prominence and established him as one of the most admired Americans and the leader of the modern Consumer Movement. Over the next thirty years and without ever holding public office, Nader built a legislative record that is the rival of any contemporary president.

To Listen to the Episode (MP3)

Film School (KUCI)

Directors Henriette Mantel and Steve Skrovan discuss their documentary, An Unreasonable Man — the story of Ralph Nader, from wannabe presidential candidate to public pariah. In 1966, General Motors, the most powerful corporation in the world, sent private investigators to dig up dirt on an obscure thirty-two year old public interest lawyer named Ralph Nader, who had written a book critical of one of their cars, the Corvair. The scandal that ensued after the smear campaign was revealed launched Ralph Nader into national prominence and established him as one of the most admired Americans and the leader of the modern Consumer Movement. Over the next thirty years and without ever holding public office, Nader built a legislative record that is the rival of any contemporary president.

To Listen to the Episode (MP3)

Will Potter: What is the “Green Scare”?

What is the “Green Scare”?

by Will Potter

Green is the New Red

...

So Why Is This Happening?

The government and corporations haven’t tried to hide the fact that this is all meant to protect corporate profits. The Department of Homeland Security, in a bulletin to law enforcement agencies, warned: “Attacks against corporations by animal rights extremists and eco-terrorists are costly to the targeted company and, over time, can undermine confidence in the economy.”

And in a leaked PowerPoint presentation given by the State Department to corporations, we learn: “Although incidents related to terrorism are most likely to make the front-page news, animal rights extremism is what’s most likely to affect your day-to-day business operations.”

Underground activists like the Animal Liberation Front and Earth Liberation Front directly threaten corporate profits by doing things like burning bulldozers or sabotaging animal research equipment. But they’re not the only ones.

The entire animal rights and environmental movements, perhaps more than any other social movements, directly threaten corporate profits. They do it every day. Every time activists encourage people to go vegan, every time they encourage people to stop driving, every time they encourage people to consume fewer resources and live simply. Those boycotts are permanent, and these industries know it. In many ways, the Green Scare, like the Red Scare, can be seen as a culture war, a war of values.

What Effect Has This Had?

The point of all this, according to the government, is to crack down on underground activists. But underground activists already know what they’re doing is illegal, and it hasn’t stopped them. In fact, it may have added fuel to the fire. For instance, the same day the SHAC 7 were convicted of “animal enterprise terrorism” for running a website that posted news of both legal and illegal actions, underground activists rescued animals from a vivisection lab and named them Jake, Lauren, Kevin, Andy, Josh, and Darius, after the defendants.

This is from the communiqué:

“And while the SHAC-7 will soon go to jail for simply speaking out on behalf of animals, those of us who have done all the nasty stuff talked about in the courts and in the media will still be free. So to those who still work with HLS and to all who abuse animals: we’re coming for you, motherfuckers.”

What Now?

So if outlandish prison sentences and “eco-terrorism” rhetoric aren’t deterring crimes or solving crimes, what’s the point?

Activists protest

Fear. It’s all about fear. The point is to protect corporate profits by instilling fear in the mainstream animal rights and environmental movements—and every other social movement paying attention—and make people think twice about using their First Amendment rights.

...

To Read the Entire Hyperlinked Essay

by Will Potter

Green is the New Red

...

So Why Is This Happening?

The government and corporations haven’t tried to hide the fact that this is all meant to protect corporate profits. The Department of Homeland Security, in a bulletin to law enforcement agencies, warned: “Attacks against corporations by animal rights extremists and eco-terrorists are costly to the targeted company and, over time, can undermine confidence in the economy.”

And in a leaked PowerPoint presentation given by the State Department to corporations, we learn: “Although incidents related to terrorism are most likely to make the front-page news, animal rights extremism is what’s most likely to affect your day-to-day business operations.”

Underground activists like the Animal Liberation Front and Earth Liberation Front directly threaten corporate profits by doing things like burning bulldozers or sabotaging animal research equipment. But they’re not the only ones.

The entire animal rights and environmental movements, perhaps more than any other social movements, directly threaten corporate profits. They do it every day. Every time activists encourage people to go vegan, every time they encourage people to stop driving, every time they encourage people to consume fewer resources and live simply. Those boycotts are permanent, and these industries know it. In many ways, the Green Scare, like the Red Scare, can be seen as a culture war, a war of values.

What Effect Has This Had?

The point of all this, according to the government, is to crack down on underground activists. But underground activists already know what they’re doing is illegal, and it hasn’t stopped them. In fact, it may have added fuel to the fire. For instance, the same day the SHAC 7 were convicted of “animal enterprise terrorism” for running a website that posted news of both legal and illegal actions, underground activists rescued animals from a vivisection lab and named them Jake, Lauren, Kevin, Andy, Josh, and Darius, after the defendants.

This is from the communiqué:

“And while the SHAC-7 will soon go to jail for simply speaking out on behalf of animals, those of us who have done all the nasty stuff talked about in the courts and in the media will still be free. So to those who still work with HLS and to all who abuse animals: we’re coming for you, motherfuckers.”

What Now?

So if outlandish prison sentences and “eco-terrorism” rhetoric aren’t deterring crimes or solving crimes, what’s the point?

Activists protest

Fear. It’s all about fear. The point is to protect corporate profits by instilling fear in the mainstream animal rights and environmental movements—and every other social movement paying attention—and make people think twice about using their First Amendment rights.

...

To Read the Entire Hyperlinked Essay

Friday, June 24, 2011

Green Cine Daily: Steve Dollar Interviews Alejandro Jodorowsky

INTERVIEW: Alejandro Jodorowsky

by Steve Dollar

Green Cine Daily

Now an avuncular 82, Alejandro Jodorowsky still has the air of a sly wizard about him—even over an Internet phone connection across the ocean in Deauville, France, where he was vacationing this week. This, after all, is the guy who once claimed: "Most directors make films with their eyes. I make films with my cojones." Not even age can wither that kind of spirit, as the Chilean émigré remains just as provocative in thought now as when he played the macho shaman in his classic cult movies El Topo (1970) and The Holy Mountain (1973), wildly influential hippie-era mindfucks that spun the tripped-out counterculture on its pointy little head.

The movies spent a long time in limbo, circulating on multiply dubbed VHS tapes for years before lingering legal issues were sorted out and they were released in remastered high-definition versions in 2006, complete with screenings at the New York Film Festival. Now they’ve been reissued in Blu-ray editions, and The Holy Mountain has a six-week run at MoMA's PS1 in Long Island City, where it will be screened three times a day in a theatrical gallery setting.

Paris has been Jodorowsky’s adoptive home since the 1960s, when his work in avant-garde street theater led him to create something he called the Panic Movement, a polymorphously perverse circus in which Antonin Artaud met lysergic freakout, and which forecast the metaphysical violence and sexuality of the films to come. As reported in the 1983 cult-film history Midnight Movies, by J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum, the movement's grandest spectacle was a four-hour event staged in 1965 called Sacramental Melodrama.

"Against music provided by a six-piece rock band, a set consisting of a smashed automobile, and the visual frisson provided by a cast of bare-chested women (each body painted a different color), Jodorowsky appeared dressed in motorcyclist leather. He slit the throats of two geese, smashed plates, had himself stripped and whipped, danced with a honey-covered woman, and taped two snakes to his chest."

There's not a huge leap from that to Holy Mountain, a landmark of visionary filmmaking pitched somewhere between magic ritual and surreal burlesque. It's a rude, rowdy satire of contemporary society framed by a transcendental quest that becomes a cosmic "gotcha!" It's also a reminder of a time when making a movie could be like a gunfight. Jodorowsky populated his cast with drunks, prostitutes, disabled dwarves, monkeys, one-eyed men, plenty of naked people and an impromptu circus of frogs and lizards in costume. The movie's mesmerizing design evokes multiple religious traditions and occult imagery, including a set constructed of original tarot-card paintings and a shocking parade of flayed, crucified lambs held aloft by villagers (the filmmaker paid a local restaurant to supply the carcasses, then returned them to be served as dinner). There is still nothing quite like it, although everyone from Dennis Hopper to Darren Aronofsky have taken cues from its method and madness.

To Read the Interview

by Steve Dollar

Green Cine Daily

Now an avuncular 82, Alejandro Jodorowsky still has the air of a sly wizard about him—even over an Internet phone connection across the ocean in Deauville, France, where he was vacationing this week. This, after all, is the guy who once claimed: "Most directors make films with their eyes. I make films with my cojones." Not even age can wither that kind of spirit, as the Chilean émigré remains just as provocative in thought now as when he played the macho shaman in his classic cult movies El Topo (1970) and The Holy Mountain (1973), wildly influential hippie-era mindfucks that spun the tripped-out counterculture on its pointy little head.

The movies spent a long time in limbo, circulating on multiply dubbed VHS tapes for years before lingering legal issues were sorted out and they were released in remastered high-definition versions in 2006, complete with screenings at the New York Film Festival. Now they’ve been reissued in Blu-ray editions, and The Holy Mountain has a six-week run at MoMA's PS1 in Long Island City, where it will be screened three times a day in a theatrical gallery setting.

Paris has been Jodorowsky’s adoptive home since the 1960s, when his work in avant-garde street theater led him to create something he called the Panic Movement, a polymorphously perverse circus in which Antonin Artaud met lysergic freakout, and which forecast the metaphysical violence and sexuality of the films to come. As reported in the 1983 cult-film history Midnight Movies, by J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum, the movement's grandest spectacle was a four-hour event staged in 1965 called Sacramental Melodrama.

"Against music provided by a six-piece rock band, a set consisting of a smashed automobile, and the visual frisson provided by a cast of bare-chested women (each body painted a different color), Jodorowsky appeared dressed in motorcyclist leather. He slit the throats of two geese, smashed plates, had himself stripped and whipped, danced with a honey-covered woman, and taped two snakes to his chest."

There's not a huge leap from that to Holy Mountain, a landmark of visionary filmmaking pitched somewhere between magic ritual and surreal burlesque. It's a rude, rowdy satire of contemporary society framed by a transcendental quest that becomes a cosmic "gotcha!" It's also a reminder of a time when making a movie could be like a gunfight. Jodorowsky populated his cast with drunks, prostitutes, disabled dwarves, monkeys, one-eyed men, plenty of naked people and an impromptu circus of frogs and lizards in costume. The movie's mesmerizing design evokes multiple religious traditions and occult imagery, including a set constructed of original tarot-card paintings and a shocking parade of flayed, crucified lambs held aloft by villagers (the filmmaker paid a local restaurant to supply the carcasses, then returned them to be served as dinner). There is still nothing quite like it, although everyone from Dennis Hopper to Darren Aronofsky have taken cues from its method and madness.

To Read the Interview

Danny Mayer: The Old, Weird Canelands

The old, weird canelands

By Danny Mayer

North of Center

“oh those fabled canelands

they come shimmering back

through two centuries”

—Warren Byrom, “Fabled Canelands”

There is a grand tradition within roots music to evoke what Greil Marcus has termed “the old, weird America,” a sort of mythical, strange underworld of the pre-modern American republic, a place where the boundaries separating blues, country, folk and mountain music do not yet seem to have taken hold. Musically, think Harry Smith’s folkways recordings of the 1920s, Woody Guthrie, Mississippi John Hurt, the Carter Family, John Hartford’s Aereoplane years, The Basement Tapes, Nebraska, and just about anything by Gillian Welch, Uncle Tupelo or Dexter Romweber.

Marcus used the term to describe how roots music connected modern America with its freakish past at risk of complete erasure: Pre-depression era Chicago confidence men like Yellow Kid Wiel selling fake stock options, nineteenth century medicine men traveling the deep south hawking healing tonics, turn of the century Shakespearean acting troupes floating down the Ohio, early republic religious revivalists setting up tents by the tens of thousands in the wilderness of Cane Ridge, KY, for weeks of Jesus, booze and massive orgies. Think of it as our national id, part fantasy and part historical record, old maps reminding new worlds.

Beginning with the album cover—a Gina Phillips tapestry depicting a pre-colonial Englishman in the opening act of clubbing an Indian—Warren Byrom’s debut solo record The Fabled Canelands is firmly situated within that old, weird America. The songs span a geographic and musical terrain bordered by the Appalachian mountains, the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, and the Louisiana Gulf coast, though the heart of Byrom’s old America seems to be set nearby the inner Kentucky bluegrass region of his home, a place once thick with stands of river cane standing over ten feet tall, now long since mostly eradicated, which European settlers encountered when first flooding into the area.

To Read the Rest of the Review

By Danny Mayer

North of Center

“oh those fabled canelands

they come shimmering back

through two centuries”

—Warren Byrom, “Fabled Canelands”

There is a grand tradition within roots music to evoke what Greil Marcus has termed “the old, weird America,” a sort of mythical, strange underworld of the pre-modern American republic, a place where the boundaries separating blues, country, folk and mountain music do not yet seem to have taken hold. Musically, think Harry Smith’s folkways recordings of the 1920s, Woody Guthrie, Mississippi John Hurt, the Carter Family, John Hartford’s Aereoplane years, The Basement Tapes, Nebraska, and just about anything by Gillian Welch, Uncle Tupelo or Dexter Romweber.

Marcus used the term to describe how roots music connected modern America with its freakish past at risk of complete erasure: Pre-depression era Chicago confidence men like Yellow Kid Wiel selling fake stock options, nineteenth century medicine men traveling the deep south hawking healing tonics, turn of the century Shakespearean acting troupes floating down the Ohio, early republic religious revivalists setting up tents by the tens of thousands in the wilderness of Cane Ridge, KY, for weeks of Jesus, booze and massive orgies. Think of it as our national id, part fantasy and part historical record, old maps reminding new worlds.

Beginning with the album cover—a Gina Phillips tapestry depicting a pre-colonial Englishman in the opening act of clubbing an Indian—Warren Byrom’s debut solo record The Fabled Canelands is firmly situated within that old, weird America. The songs span a geographic and musical terrain bordered by the Appalachian mountains, the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, and the Louisiana Gulf coast, though the heart of Byrom’s old America seems to be set nearby the inner Kentucky bluegrass region of his home, a place once thick with stands of river cane standing over ten feet tall, now long since mostly eradicated, which European settlers encountered when first flooding into the area.

To Read the Rest of the Review

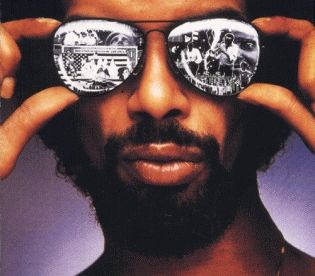

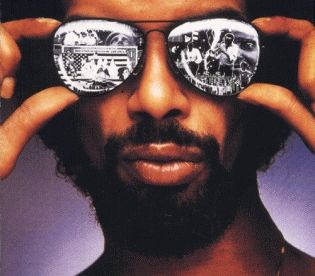

DJ Monk One: The Last Thing I Learned From Gil Scott-Heron

A tribute by DJ Monk One to accompany an hour long mix of Gil Scott Heron:

Ill Doctrine: The Last Thing I Learned From Gil Scott-Heron

Ill Doctrine: The Last Thing I Learned From Gil Scott-Heron

Johann Hari: In the age of distraction, we will need books more than ever

In the age of distraction, we will need books more than ever

by Johann Hari

...

We have now reached that point. And here's the function that the book - the paper book that doesn't beep or flash or link or let you watch a thousand videos all at once - does for you that nothing else will. It gives you the capacity for deep, linear concentration. As Ulin puts it: "Reading is an act of resistance in a landscape of distraction.... It requires us to pace ourselves. It returns us to a reckoning with time. In the midst of a book, we have no choice but to be patient, to take each thing in its moment, to let the narrative prevail. We regain the world by withdrawing from it just a little, by stepping back from the noise."

A book has a different relationship to time than a TV show or a Facebook update. It says that something was worth taking from the endless torrent of data and laying down on an object that will still look the same a hundred years from now. The French writer Jean-Phillipe De Tonnac says "the true function of books is to safeguard the things that forgetfulness constantly threatens to destroy." It's precisely because it is not immediate - because it doesn't know what happened five minutes ago in Kazakhstan, or in Charlie Sheen's apartment - that the book matters.

That's why we need books, and why I believe they will survive. Because most humans have a desire to engage in deep thought and deep concentration. Those muscles are necessary for deep feeling and deep engagement. Most humans don't just want mental snacks forever; they also want meals. The twenty hours it takes to read a book require a sustained concentration it's hard to get anywhere else. Sure, you can do that with a DVD boxset too - but your relationship to TV will always ultimately be that of a passive spectator. With any book, you are the co-creator, imagining it as you go. As Kurt Vonnegut out it, literature is the only art form in which the audience plays the score.

I'm not against e-books in principle - I'm tempted by the Kindle - but the more they become interactive and linked, the more they multitask and offer a hundred different functions, the less they will be able to preserve the aspects of the book that we actually need. An e-book reader that does a lot will not, in the end, be a book. The object needs to remain dull so the words - offering you the most electric sensation of all: insight into another person's internal life - can sing.

So how do we preserve the mental space for the book? We are the first generation to ever use the internet, and when I look at how we are reacting to it, I keep thinking of the Inuit communities I met in the Arctic, who were given alcohol and sugar for the first time a generation ago, and guzzled them so rapidly they were now sunk in obesity and alcoholism. Sugar, alcohol and the web are all amazing pleasures and joys - but we need to know how to handle them without letting them addle us.

The idea of keeping yourself on a digital diet will, I suspect, become mainstream soon. Just as I've learned not to stock my fridge with tempting carbs, I've learned to limit my exposure to the web - and to love it in the limited window I allow myself. I have installed the program 'Freedom' on my laptop: it will disconnect you from the web for however long you tell it to. It's the Ritalin I need for my web-induced ADHD. I make sure I activate it so I can dive into the more permanent world of the printed page for at least two hours a day, or I find myself with a sense of endless online connection that leaves you oddly disconnected from yourself.

T.S. Eliot called books "the still point of the turning world." He was right. It turns out, in the age of super-speed broadband we need dead trees to have living minds.

To Read the Entire Essay

by Johann Hari

...

We have now reached that point. And here's the function that the book - the paper book that doesn't beep or flash or link or let you watch a thousand videos all at once - does for you that nothing else will. It gives you the capacity for deep, linear concentration. As Ulin puts it: "Reading is an act of resistance in a landscape of distraction.... It requires us to pace ourselves. It returns us to a reckoning with time. In the midst of a book, we have no choice but to be patient, to take each thing in its moment, to let the narrative prevail. We regain the world by withdrawing from it just a little, by stepping back from the noise."

A book has a different relationship to time than a TV show or a Facebook update. It says that something was worth taking from the endless torrent of data and laying down on an object that will still look the same a hundred years from now. The French writer Jean-Phillipe De Tonnac says "the true function of books is to safeguard the things that forgetfulness constantly threatens to destroy." It's precisely because it is not immediate - because it doesn't know what happened five minutes ago in Kazakhstan, or in Charlie Sheen's apartment - that the book matters.

That's why we need books, and why I believe they will survive. Because most humans have a desire to engage in deep thought and deep concentration. Those muscles are necessary for deep feeling and deep engagement. Most humans don't just want mental snacks forever; they also want meals. The twenty hours it takes to read a book require a sustained concentration it's hard to get anywhere else. Sure, you can do that with a DVD boxset too - but your relationship to TV will always ultimately be that of a passive spectator. With any book, you are the co-creator, imagining it as you go. As Kurt Vonnegut out it, literature is the only art form in which the audience plays the score.

I'm not against e-books in principle - I'm tempted by the Kindle - but the more they become interactive and linked, the more they multitask and offer a hundred different functions, the less they will be able to preserve the aspects of the book that we actually need. An e-book reader that does a lot will not, in the end, be a book. The object needs to remain dull so the words - offering you the most electric sensation of all: insight into another person's internal life - can sing.

So how do we preserve the mental space for the book? We are the first generation to ever use the internet, and when I look at how we are reacting to it, I keep thinking of the Inuit communities I met in the Arctic, who were given alcohol and sugar for the first time a generation ago, and guzzled them so rapidly they were now sunk in obesity and alcoholism. Sugar, alcohol and the web are all amazing pleasures and joys - but we need to know how to handle them without letting them addle us.

The idea of keeping yourself on a digital diet will, I suspect, become mainstream soon. Just as I've learned not to stock my fridge with tempting carbs, I've learned to limit my exposure to the web - and to love it in the limited window I allow myself. I have installed the program 'Freedom' on my laptop: it will disconnect you from the web for however long you tell it to. It's the Ritalin I need for my web-induced ADHD. I make sure I activate it so I can dive into the more permanent world of the printed page for at least two hours a day, or I find myself with a sense of endless online connection that leaves you oddly disconnected from yourself.

T.S. Eliot called books "the still point of the turning world." He was right. It turns out, in the age of super-speed broadband we need dead trees to have living minds.

To Read the Entire Essay

Anil Menon's The Beast with Nine Million Feet: In a World of Bonsai People -- Believe in the Technology of Foolishness

"What are you angry about, dear one? That Soda-kaka wants my help, or that he wants my time?"

"Our time," she mumbled. "I wish you weren't so involved with politics."

"Yes, life would've been a lot simpler if I'd remained a scientist, if I hadn't started Free Life or become a voice for the voiceless."

"Sivan-bau!" A fisher-woman had gotten to her feet and was gesturing to others around her. "That's Sivan-bhau."

"So why did you?" asked Tara, tugging at her father's hand. "Why did you ever leave science? Why did you start Free Life? Why didn't you call at least once? Not even once. We didn't even know if you were dead or alive. I was so afraid I'd find out through the news. I got so tired of waiting. You care about everyone but us."

Tara felt tears trying to make a break for it. She blinked hard to put down the rebellion. "These look nice." She pointed to some green chillies.

"If I'd stayed in touch, it would have got all of you in even more trouble. I was trying not to make a bad situation worse. As to why I stopped being just a scientist, the answer is very simple. I realized millions of people were being thrown away. You've seen bonsai trees, no? The same acorn that can produce a hundred-foot oak tree can be made into a tree that fits a saucer."

Tara nodded. There was something so creepy about bonsai.

"In a way, that's what we do with millions of humans. If humans are given decent nutrition, a good education, some love, pushy parents and high expectations, they generally bloom, flourish, and reach their full potential. But take away resources, take away a person's freedoms, keep them in ignorance, bind them with superstition and fear, convince them of their inferiority, then you've created a bonsai person. Incomplete, stunted, denied even the capacity to hope. When I realized I was living in a world of bonsai people, and that I escaped only because I'd won the genetic lottery [editor's note: Sivan-bhau is talking about his scientific discovery that led to wealth, not that he has superior genetics], it was impossible to close my eyes and pretend all was well. So I'm doing my bit. Would you have preferred a father who didn't?"

"Sometimes... I wish I could see things the way you do."

"You do just fine." He squeezed her shoulder. "Sita has raised a wonderful daughter."

"But you think the best of everyone. Even when they aren't. And you have no idea who I am. Not really. I'm not noble at all. I'm so ordinary."

To her horror, Tara felt tears plotting another revolt.

...

"Don't be sorry, Tara. I admire nobility, but I don't want nobles. If my cause needed heroes and knights, I wouldn't do it. I believe we can create a world where poverty, violence, inequity and despair will only be a bad memory. Yes, it's foolish, but take my hand, dear one, and believe with me in the technology of foolishness. And I don't care if you're ordinary, underordinary or superordinary. I don't need reasons to love you. It's one the unexpected side-effects of beaing a father. Clear?" (Young-Zubaan, 2009: 124-126)

Thursday, June 23, 2011

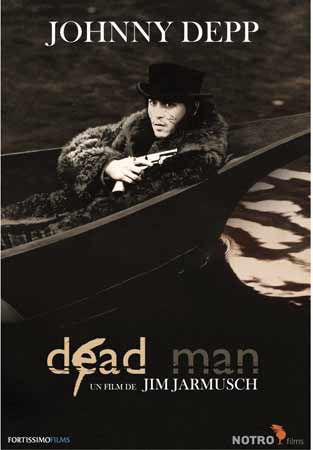

Melissa Anne-Marie Curley: Dead Men Don’t Lie -- Sacred Texts in Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man and Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai

Dead Men Don’t Lie: Sacred Texts in Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man and Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai.

by Melissa Anne-Marie Curley

Journal of Religion and Film

[1] In 1995, American auteur Jim Jarmusch released his experimental western Dead Man. In 1999, Jarmusch released Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai, which played with the genres of the samurai picture and the mafia movie. In this paper, I argue that these two films share a single narrative, and that narrative is about books and what books can do. Taking up Mircea Eliade’s notion of the sacred text as a manual for recovering primordial time, I suggest that the protagonists of both films should be understood as Eliade’s “religious man.”

[2] Ghost Dog is a spectacularly cool black hitman loosely associated with the fading Vargo mafia family—Louie, a lesser member, once saved his life and since then he has served Louie as a retainer, adhering strictly to the rules of the samurai code. The film begins with Ghost Dog botching a job involving Louise Vargo, the daughter of the head of the family; a hit is thus ordered on Ghost Dog himself. The rest of the film traces him as he engineers his inevitable death in such a way that he can be killed both by and for Louie. The dead man in Dead Man is a spectacularly uncool white accountant named William Blake who, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, moves west to the town of Machine, only to find that the job promised him by a Mr. Dickinson has been given away. Through a series of misadventures, Blake ends up getting shot by Dickinson’s son; Blake kills the son in self-defense, Dickinson Sr. places a bounty on his head, and the rest of the film follows him on the run through the badlands, until finally he reaches the water and is set adrift in a boat to die.

[3] These narrative differences demand, naturally, that Dead Man and Ghost Dog exist in different aesthetic universes: one is set in a fin-de-siècle American West and the other in postmodern New York City; one was shot in black and white and the other in color; one was scored by Neil Young and the other by the Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA. Nonetheless, it is easy to compare Dead Man and Ghost Dog. They’re both genre movies and these particular genres have a special family resemblance.1 And despite the distance in terms of historical and geographical location, they also exist in the same narrative universe; Jarmusch tells us this by having the same character appear in both. In Dead Man, he has a lead role—Gary Farmer plays Nobody, a Plains Indian who guides the film’s protagonist through hell, despite his antipathy towards “stupid fucking white men.” In Ghost Dog, he has a cameo—Farmer plays a pigeon keeper who gets just one line: “stupid fucking white men.” Stay through the credits and you find that here too the character’s name is Nobody.

[4] I want to claim though that the two movies are not just comparable—Jarmusch has in fact made the same movie twice. Ghost Dog is, according to the samurai code, committed to live as one already dead; from the first scene then, he is a dead man. Dead Man too has a protagonist who is dead from the outset although we don’t learn this until the end. The film opens with Blake on a train; the train fireman asks him “doesn’t this remind you of when you were in the boat?”—if, in other words, it reminds him of the last scene of the movie, when he dies. So both movies have protagonists who, while appearing to be alive, are already dead; both these dead men are sentenced to death by their employers; and both are occupied with writing what Jarmusch in each case refers to as poetry—a “poetry of war” or a poetry “written in blood.” This poetry is in neither case original: our heroes are tasked with recirculating old texts, not with generating new ones.

[5] Jarmusch himself has old texts circulate through both movies, as props, plot points, and interstitial titles. Gregory Salyer reads Dead Man as exposing the American fear of inauthenticity; in Dead Man, he suggests, “writing is the primary medium for disseminating lies.”2 I would suggest that since Jarmusch himself is a writer—a disseminator of lies—he is also, in these films, exploring the possibility that the lies of the written text can be appropriated in such a way that the reader’s performance turns them into the truth. There are for Jarmusch always two levels to the book: the book as it is located historically and the book as it is appropriated by his heroes. The effect of each appropriation is to disrupt historical time. Acting out the demands of old books becomes then, for Ghost Dog and Blake, a way to refuse their historical locations and force a return to the primordial. Mircea Eliade has famously suggested that “religious man refuses to live solely in what, in modern terms, is called the historical present; he attempts to regain a sacred time”3 through the reenactment of sacred texts. I will argue that the protagonists of Ghost Dog and Dead Men should be understood on these terms as religious men, working with sacred texts, despite the fact that, as we will see, none of the books they read are part of any standard religious canon.

[6] There are two Japanese texts circulating in Ghost Dog: Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure and Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s Rashōmon and Other Stories . Rashōmon serves as Ghost Dog’s linking text. Inside the space of the film, the book links Ghost Dog to the two women in the movie, and the two women to each other. Louise Vargo gives the book to Ghost Dog just after he mistakenly shoots her boyfriend in front of her, telling him “ancient Japan was a pretty strange place”; he gives it to Pearline, a young girl who introduces herself to him in the park, as an initiatory gesture of friendship; and at the end of the movie, Pearline returns it to Ghost Dog. He gives it to Louie before he dies; Louise retrieves it from Louie, covered in blood. The physical object of Rashōmon is thus the sign of the continuing blood relationship between the Vargo family and its heir, Louise, and Ghost Dog and his heir, Pearline. Outside the space of the film, the book links Jarmusch’s movie to Akira Kurosawa’s famous adaptation of Rashōmon.4 Ryōko Otomo points out that the stories collected in Rashōmon are modern re-workings of legends from the classical period, “a product of eclecticism”5 —Akutagawa’s book and Kurosawa’s adaptation both problematize the notion of singular ownership of a text. What Rashōmon signals inside and outside the film then is that texts are not stable; texts circulate and because of this circulation they are at once elusive and open to appropriation. Otomo argues that for Jarmusch Rashōmon and the Hagakure function as “couriers of the true”: the “film pretends as if there were the hidden sacred true, and as if words/languages/texts carried it within.”6 I break with her reading here. “Yabu no naka,” the story to which Jarmusch links his movie, is precisely about the way that a story produces multiple truths in the telling. Texts are for Jarmusch not containers of truth, but props in the performance that produces truth.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

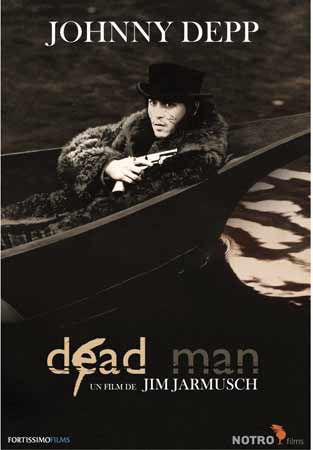

by Melissa Anne-Marie Curley

Journal of Religion and Film

[1] In 1995, American auteur Jim Jarmusch released his experimental western Dead Man. In 1999, Jarmusch released Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai, which played with the genres of the samurai picture and the mafia movie. In this paper, I argue that these two films share a single narrative, and that narrative is about books and what books can do. Taking up Mircea Eliade’s notion of the sacred text as a manual for recovering primordial time, I suggest that the protagonists of both films should be understood as Eliade’s “religious man.”

[2] Ghost Dog is a spectacularly cool black hitman loosely associated with the fading Vargo mafia family—Louie, a lesser member, once saved his life and since then he has served Louie as a retainer, adhering strictly to the rules of the samurai code. The film begins with Ghost Dog botching a job involving Louise Vargo, the daughter of the head of the family; a hit is thus ordered on Ghost Dog himself. The rest of the film traces him as he engineers his inevitable death in such a way that he can be killed both by and for Louie. The dead man in Dead Man is a spectacularly uncool white accountant named William Blake who, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, moves west to the town of Machine, only to find that the job promised him by a Mr. Dickinson has been given away. Through a series of misadventures, Blake ends up getting shot by Dickinson’s son; Blake kills the son in self-defense, Dickinson Sr. places a bounty on his head, and the rest of the film follows him on the run through the badlands, until finally he reaches the water and is set adrift in a boat to die.

[3] These narrative differences demand, naturally, that Dead Man and Ghost Dog exist in different aesthetic universes: one is set in a fin-de-siècle American West and the other in postmodern New York City; one was shot in black and white and the other in color; one was scored by Neil Young and the other by the Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA. Nonetheless, it is easy to compare Dead Man and Ghost Dog. They’re both genre movies and these particular genres have a special family resemblance.1 And despite the distance in terms of historical and geographical location, they also exist in the same narrative universe; Jarmusch tells us this by having the same character appear in both. In Dead Man, he has a lead role—Gary Farmer plays Nobody, a Plains Indian who guides the film’s protagonist through hell, despite his antipathy towards “stupid fucking white men.” In Ghost Dog, he has a cameo—Farmer plays a pigeon keeper who gets just one line: “stupid fucking white men.” Stay through the credits and you find that here too the character’s name is Nobody.

[4] I want to claim though that the two movies are not just comparable—Jarmusch has in fact made the same movie twice. Ghost Dog is, according to the samurai code, committed to live as one already dead; from the first scene then, he is a dead man. Dead Man too has a protagonist who is dead from the outset although we don’t learn this until the end. The film opens with Blake on a train; the train fireman asks him “doesn’t this remind you of when you were in the boat?”—if, in other words, it reminds him of the last scene of the movie, when he dies. So both movies have protagonists who, while appearing to be alive, are already dead; both these dead men are sentenced to death by their employers; and both are occupied with writing what Jarmusch in each case refers to as poetry—a “poetry of war” or a poetry “written in blood.” This poetry is in neither case original: our heroes are tasked with recirculating old texts, not with generating new ones.

[5] Jarmusch himself has old texts circulate through both movies, as props, plot points, and interstitial titles. Gregory Salyer reads Dead Man as exposing the American fear of inauthenticity; in Dead Man, he suggests, “writing is the primary medium for disseminating lies.”2 I would suggest that since Jarmusch himself is a writer—a disseminator of lies—he is also, in these films, exploring the possibility that the lies of the written text can be appropriated in such a way that the reader’s performance turns them into the truth. There are for Jarmusch always two levels to the book: the book as it is located historically and the book as it is appropriated by his heroes. The effect of each appropriation is to disrupt historical time. Acting out the demands of old books becomes then, for Ghost Dog and Blake, a way to refuse their historical locations and force a return to the primordial. Mircea Eliade has famously suggested that “religious man refuses to live solely in what, in modern terms, is called the historical present; he attempts to regain a sacred time”3 through the reenactment of sacred texts. I will argue that the protagonists of Ghost Dog and Dead Men should be understood on these terms as religious men, working with sacred texts, despite the fact that, as we will see, none of the books they read are part of any standard religious canon.

[6] There are two Japanese texts circulating in Ghost Dog: Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure and Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s Rashōmon and Other Stories . Rashōmon serves as Ghost Dog’s linking text. Inside the space of the film, the book links Ghost Dog to the two women in the movie, and the two women to each other. Louise Vargo gives the book to Ghost Dog just after he mistakenly shoots her boyfriend in front of her, telling him “ancient Japan was a pretty strange place”; he gives it to Pearline, a young girl who introduces herself to him in the park, as an initiatory gesture of friendship; and at the end of the movie, Pearline returns it to Ghost Dog. He gives it to Louie before he dies; Louise retrieves it from Louie, covered in blood. The physical object of Rashōmon is thus the sign of the continuing blood relationship between the Vargo family and its heir, Louise, and Ghost Dog and his heir, Pearline. Outside the space of the film, the book links Jarmusch’s movie to Akira Kurosawa’s famous adaptation of Rashōmon.4 Ryōko Otomo points out that the stories collected in Rashōmon are modern re-workings of legends from the classical period, “a product of eclecticism”5 —Akutagawa’s book and Kurosawa’s adaptation both problematize the notion of singular ownership of a text. What Rashōmon signals inside and outside the film then is that texts are not stable; texts circulate and because of this circulation they are at once elusive and open to appropriation. Otomo argues that for Jarmusch Rashōmon and the Hagakure function as “couriers of the true”: the “film pretends as if there were the hidden sacred true, and as if words/languages/texts carried it within.”6 I break with her reading here. “Yabu no naka,” the story to which Jarmusch links his movie, is precisely about the way that a story produces multiple truths in the telling. Texts are for Jarmusch not containers of truth, but props in the performance that produces truth.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Wednesday, June 22, 2011

“If a Tree Falls”: New Documentary on Daniel McGowan, Earth Liberation Front and Green Scare

“If a Tree Falls”: New Documentary on Daniel McGowan, Earth Liberation Front and Green Scare

Democracy Now

A new documentary, "If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front," tells the story of environmental activist Daniel McGowan. Four years ago this month, McGowan was sentenced to a seven-year term for his role in two acts of politically motivated arson in 2001 to protest extensive logging in the Pacific Northwest—starting fires at a lumber company and an experimental tree farm in Oregon. The judge ruled he had committed an act of terrorism, even though no one was hurt in any of the actions. McGowan participated in the arsons as a member of the Earth Liberation Front but left the group after the second fire led him to become disillusioned. He was arrested years later after a key member of the Earth Liberation Front—himself facing the threat of lengthy jail time—turned government informant. McGowan ultimately reached a plea deal but refused to cooperate with the government’s case. As a result, the government sought a "terrorism enhancement" to add extra time to his sentence. McGowan is currently jailed in a secretive prison unit known as Communication Management Units, or CMUs, in Marion, Illinois. We play an excerpt from the film and speak with the film’s director, Marshall Curry. We also speak with Andrew Stepanian, an animal rights activist who was imprisoned at the same CMU as McGowan, and with Will Potter, a freelance reporter who writes about how the so-called “war on terror” affects civil liberties.

Marshall Curry, filmmaker and co-director of the new documentary, If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front.

Andrew Stepanian, an animal rights activist who was jailed at the same CMU as Daniel McGowan for six months. Andrew was freed from prison in 2009 after serving a total of 31 months behind bars.

Will Potter, freelance reporter who focuses on how the war on terrorism affects civil liberties. He runs the blog, “GreenIsTheNewRed.com.” He his also the author of the new book Green is the New Red: An Insider’s Account of a Social Movement Under Siege.

To Watch/Listen/Read

Democracy Now

A new documentary, "If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front," tells the story of environmental activist Daniel McGowan. Four years ago this month, McGowan was sentenced to a seven-year term for his role in two acts of politically motivated arson in 2001 to protest extensive logging in the Pacific Northwest—starting fires at a lumber company and an experimental tree farm in Oregon. The judge ruled he had committed an act of terrorism, even though no one was hurt in any of the actions. McGowan participated in the arsons as a member of the Earth Liberation Front but left the group after the second fire led him to become disillusioned. He was arrested years later after a key member of the Earth Liberation Front—himself facing the threat of lengthy jail time—turned government informant. McGowan ultimately reached a plea deal but refused to cooperate with the government’s case. As a result, the government sought a "terrorism enhancement" to add extra time to his sentence. McGowan is currently jailed in a secretive prison unit known as Communication Management Units, or CMUs, in Marion, Illinois. We play an excerpt from the film and speak with the film’s director, Marshall Curry. We also speak with Andrew Stepanian, an animal rights activist who was imprisoned at the same CMU as McGowan, and with Will Potter, a freelance reporter who writes about how the so-called “war on terror” affects civil liberties.

Marshall Curry, filmmaker and co-director of the new documentary, If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front.

Andrew Stepanian, an animal rights activist who was jailed at the same CMU as Daniel McGowan for six months. Andrew was freed from prison in 2009 after serving a total of 31 months behind bars.

Will Potter, freelance reporter who focuses on how the war on terrorism affects civil liberties. He runs the blog, “GreenIsTheNewRed.com.” He his also the author of the new book Green is the New Red: An Insider’s Account of a Social Movement Under Siege.

To Watch/Listen/Read

Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jethá: Another Well-Intentioned Inquisition

Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality

Christopher Ryan, Ph.D. & Cacilda Jethá, M.D.

Introduction: Another Well-Intentioned Inquisition

Forget what you’ve heard about human beings having descended from the apes. We didn’t descend from apes. We are apes. Metaphorically and factually, Homo sapiens is one of the five surviving species of great apes, along with chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans (gibbons are considered a “lesser ape”). We shared a common ancestor with two of these apes—bonobos and chimps—just five million years ago. That’s “the day before yesterday” in evolutionary terms. The fine print distinguishing humans from the other great apes is regarded as “wholly artificial” by most primatologists these days.

If we’re “above” nature, it’s only in the sense that a shaky-legged surfer is “above” the ocean. Even if we never slip (and we all do), our inner nature can pull us under at any moment. Those of us raised in the West have been assured that we humans are special, unique among living things, above and beyond the world around us, exempt from the humilities and humiliations that pervade and define animal life. The natural world lies below and beneath us, a cause for shame, disgust, or alarm; something smelly and messy to be hidden behind closed doors, drawn curtains, and minty freshness. Or we overcompensate and imagine nature floating angelically in soft focus up above, innocent, noble, balanced, and wise.

Like bonobos and chimps, we are the randy descendents of hypersexual ancestors. At first blush, this may seem an overstatement, but it’s a truth that should have become common knowledge long ago. Conventional notions of monogamous, till-death-do-us-part marriage strain under the dead weight of a false narrative that insists we’re something else. What is the essence of human sexuality and how did it get to be that way? In the following pages, we’ll explain how seismic cultural shifts that began about ten thousand years ago rendered the true story of human sexuality so subversive and threatening that for centuries it has been silenced by religious authorities, pathologized by physicians, studiously ignored by scientists, and covered up by moralizing therapists.

Deep conflicts rage at the heart of modern sexuality. Our cultivated ignorance is devastating. The campaign to obscure the true nature of our species’ sexuality leaves half our marriages collapsing under an unstoppable tide of swirling sexual frustration, libido-killing boredom, impulsive betrayal, dysfunction, confusion, and shame. Serial monogamy stretches before (and behind) many of us like an archipelago of failure: isolated islands of transitory happiness in a cold, dark sea of disappointment. And how many of the couples who manage to stay together for the long haul have done so by resigning themselves to sacrificing their eroticism on the altar of three of life’s irreplaceable joys: family stability, companionship, and emotional, if not sexual, intimacy? Are those who aspire to these joys cursed by nature to preside over the slow strangulation of their partner’s libido?

The Spanish word esposas means both “wives” and “handcuffs.” In English, some men ruefully joke about the ball and chain. There’s good reason marriage is often depicted and mourned as the beginning of the end of a man’s sexual life. And women fare no better. Who wants to share her life with a man who feels trapped and diminished by his love for her, whose honor marks the limits of his freedom? Who wants to spend her life apologizing for being just one woman?

Yes, something is seriously wrong. The American Medical Association reports that some 42 percent of American women suffer from sexual dysfunction, while Viagra breaks sales records year after year. Worldwide, pornography is reported to rake in anywhere from fifty-seven to a hundred-billion-dollars annually. In the United States, it generates more revenue than CBS, NBC, and ABC combined, and more than all professional football, baseball, and basketball franchises. According to U.S. News and World Report, “Americans spend more money at strip clubs than at Broadway, off-Broadway, regional and nonprofit theaters, the opera, the ballet and jazz and classical music performances—combined.”

There’s no denying that we’re a species with a sweet tooth for sex. Meanwhile, so-called traditional marriage appears to be under assault from all sides—as it collapses from within. Even the most ardent defenders of normal sexuality buckle under its weight, as never-ending bipartisan perp-walks of politicians (Clinton, Vitter, Gingrich, Craig, Foley, Spitzer, Sanford) and religious figures (Haggard, Swaggert, Bakker) trumpet their support of family values before slinking off to private assignations with lovers, prostitutes, and interns.

Denial hasn’t worked. Hundreds of Catholic priests have confessed to thousands of sex crimes against children in the past few decades alone. In 2008, the Catholic Church paid $436 million in compensation for sexual abuse. More than a fifth of the victims were under ten years old. This we know. Dare we even imagine the suffering such crimes have caused in the seventeen centuries since a sexual life was perversely forbidden to priests in the earliest known papal decree: the Decreta and Cum in unum of Pope Siricius (c. 385)? What is the moral debt owed to the forgotten victims of this misguided rejection of basic human sexuality?

To Read the Rest of the Introduction

Christopher Ryan, Ph.D. & Cacilda Jethá, M.D.

Introduction: Another Well-Intentioned Inquisition

Forget what you’ve heard about human beings having descended from the apes. We didn’t descend from apes. We are apes. Metaphorically and factually, Homo sapiens is one of the five surviving species of great apes, along with chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans (gibbons are considered a “lesser ape”). We shared a common ancestor with two of these apes—bonobos and chimps—just five million years ago. That’s “the day before yesterday” in evolutionary terms. The fine print distinguishing humans from the other great apes is regarded as “wholly artificial” by most primatologists these days.

If we’re “above” nature, it’s only in the sense that a shaky-legged surfer is “above” the ocean. Even if we never slip (and we all do), our inner nature can pull us under at any moment. Those of us raised in the West have been assured that we humans are special, unique among living things, above and beyond the world around us, exempt from the humilities and humiliations that pervade and define animal life. The natural world lies below and beneath us, a cause for shame, disgust, or alarm; something smelly and messy to be hidden behind closed doors, drawn curtains, and minty freshness. Or we overcompensate and imagine nature floating angelically in soft focus up above, innocent, noble, balanced, and wise.

Like bonobos and chimps, we are the randy descendents of hypersexual ancestors. At first blush, this may seem an overstatement, but it’s a truth that should have become common knowledge long ago. Conventional notions of monogamous, till-death-do-us-part marriage strain under the dead weight of a false narrative that insists we’re something else. What is the essence of human sexuality and how did it get to be that way? In the following pages, we’ll explain how seismic cultural shifts that began about ten thousand years ago rendered the true story of human sexuality so subversive and threatening that for centuries it has been silenced by religious authorities, pathologized by physicians, studiously ignored by scientists, and covered up by moralizing therapists.

Deep conflicts rage at the heart of modern sexuality. Our cultivated ignorance is devastating. The campaign to obscure the true nature of our species’ sexuality leaves half our marriages collapsing under an unstoppable tide of swirling sexual frustration, libido-killing boredom, impulsive betrayal, dysfunction, confusion, and shame. Serial monogamy stretches before (and behind) many of us like an archipelago of failure: isolated islands of transitory happiness in a cold, dark sea of disappointment. And how many of the couples who manage to stay together for the long haul have done so by resigning themselves to sacrificing their eroticism on the altar of three of life’s irreplaceable joys: family stability, companionship, and emotional, if not sexual, intimacy? Are those who aspire to these joys cursed by nature to preside over the slow strangulation of their partner’s libido?

The Spanish word esposas means both “wives” and “handcuffs.” In English, some men ruefully joke about the ball and chain. There’s good reason marriage is often depicted and mourned as the beginning of the end of a man’s sexual life. And women fare no better. Who wants to share her life with a man who feels trapped and diminished by his love for her, whose honor marks the limits of his freedom? Who wants to spend her life apologizing for being just one woman?

Yes, something is seriously wrong. The American Medical Association reports that some 42 percent of American women suffer from sexual dysfunction, while Viagra breaks sales records year after year. Worldwide, pornography is reported to rake in anywhere from fifty-seven to a hundred-billion-dollars annually. In the United States, it generates more revenue than CBS, NBC, and ABC combined, and more than all professional football, baseball, and basketball franchises. According to U.S. News and World Report, “Americans spend more money at strip clubs than at Broadway, off-Broadway, regional and nonprofit theaters, the opera, the ballet and jazz and classical music performances—combined.”

There’s no denying that we’re a species with a sweet tooth for sex. Meanwhile, so-called traditional marriage appears to be under assault from all sides—as it collapses from within. Even the most ardent defenders of normal sexuality buckle under its weight, as never-ending bipartisan perp-walks of politicians (Clinton, Vitter, Gingrich, Craig, Foley, Spitzer, Sanford) and religious figures (Haggard, Swaggert, Bakker) trumpet their support of family values before slinking off to private assignations with lovers, prostitutes, and interns.

Denial hasn’t worked. Hundreds of Catholic priests have confessed to thousands of sex crimes against children in the past few decades alone. In 2008, the Catholic Church paid $436 million in compensation for sexual abuse. More than a fifth of the victims were under ten years old. This we know. Dare we even imagine the suffering such crimes have caused in the seventeen centuries since a sexual life was perversely forbidden to priests in the earliest known papal decree: the Decreta and Cum in unum of Pope Siricius (c. 385)? What is the moral debt owed to the forgotten victims of this misguided rejection of basic human sexuality?

To Read the Rest of the Introduction

Tim Dickinson: How Roger Ailes Built the Fox News Fear Factory

How Roger Ailes Built the Fox News Fear Factory: The onetime Nixon operative has created the most profitable propaganda machine in history. Inside America's Unfair and Imbalanced Network

by Tim Dickinson

Roling Stone

At the Fox News holiday party the year the network overtook archrival CNN in the cable ratings, tipsy employees were herded down to the basement of a Midtown bar in New York. As they gathered around a television mounted high on the wall, an image flashed to life, glowing bright in the darkened tavern: the MSNBC logo. A chorus of boos erupted among the Fox faithful. The CNN logo followed, and the catcalls multiplied. Then a third slide appeared, with a telling twist. In place of the logo for Fox News was a beneficent visage: the face of the network’s founder. The man known to his fiercest loyalists simply as "the Chairman" – Roger Ailes.

“It was as though we were looking at Mao,” recalls Charlie Reina, a former Fox News producer. The Foxistas went wild. They let the dogs out. Woof! Woof! Woof! Even those who disliked the way Ailes runs his network joined in the display of fealty, given the culture of intimidation at Fox News. “It’s like the Soviet Union or China: People are always looking over their shoulders,” says a former executive with the network’s parent, News Corp. “There are people who turn people in.”

The key to decoding Fox News isn’t Bill O’Reilly or Sean Hannity. It isn’t even News Corp. chief Rupert Murdoch. To understand what drives Fox News, and what its true purpose is, you must first understand Chairman Ailes. “He is Fox News,” says Jane Hall, a decade-long Fox commentator who defected over Ailes’ embrace of the fear-mongering Glenn Beck. “It’s his vision. It’s a reflection of him.”

Ailes runs the most profitable – and therefore least accountable – head of the News Corp. hydra. Fox News reaped an estimated profit of $816 million last year – nearly a fifth of Murdoch’s global haul. The cable channel’s earnings rivaled those of News Corp.’s entire film division, which includes 20th Century Fox, and helped offset a slump at Murdoch’s beloved newspapers unit, which took a $3 billion write-down after acquiring The Wall Street Journal. With its bare-bones newsgathering operation – Fox News has one-third the staff and 30 fewer bureaus than CNN – Ailes generates profit margins above 50 percent. Nearly half comes from advertising, and the rest is dues from cable companies. Fox News now reaches 100 million households, attracting more viewers than all other cable-news outlets combined, and Ailes aims for his network to “throw off a billion in profits.”

The outsize success of Fox News gives Ailes a free hand to shape the network in his own image. "Murdoch has almost no involvement with it at all," says Michael Wolff, who spent nine months embedded at News Corp. researching a biography of the Australian media giant. "People are afraid of Roger. Murdoch is, himself, afraid of Roger. He has amassed enormous power within the company – and within the country – from the success of Fox News."