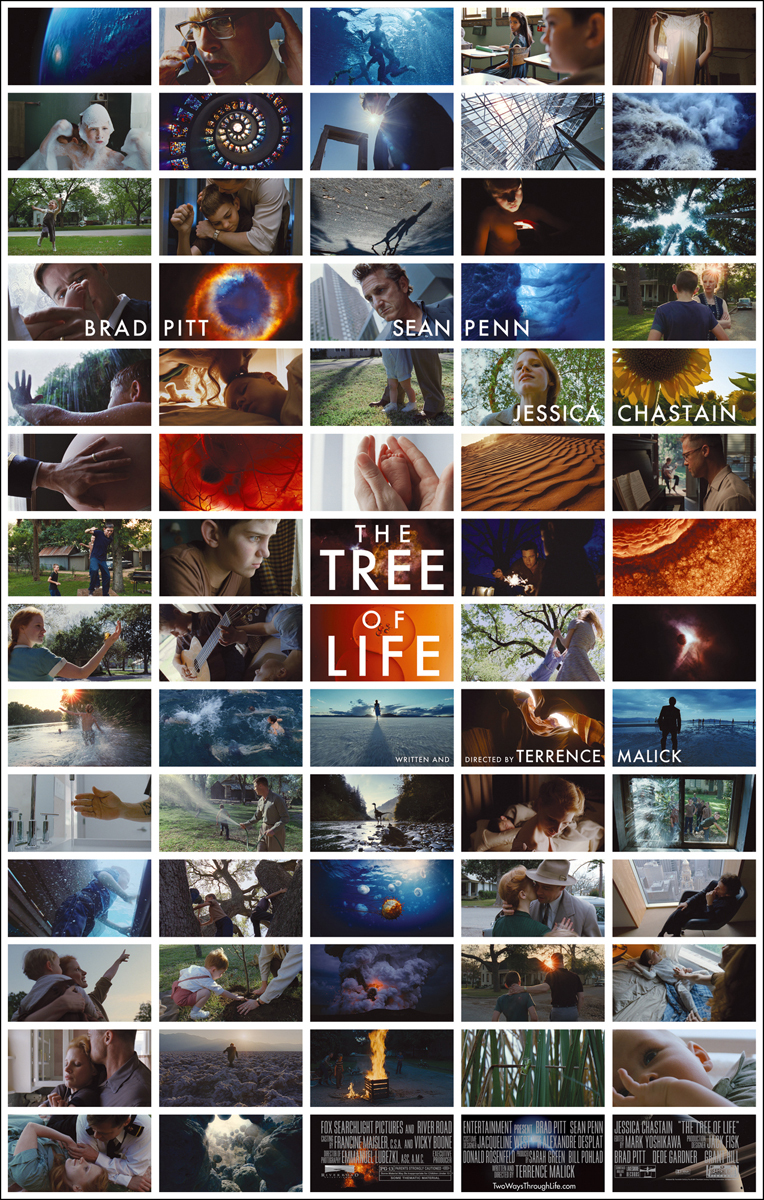

Jeff Reichert on The Tree of Life

Reverse Shot

“There is grandeur in this view of life . . . from so simple a beginning, endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” —Charles Darwin

When Auguste and Louis Lumière first shined a light through a thin celluloid strip imprinted with sequential images, casting the shaky, colorless, but nevertheless strikingly realistic representation of an arriving locomotive onto a screen set before an audience, they could never have imagined their simple beginning—a hand-cranked gadget that elegantly paired cutting-edge photochemical processes with basic mechanical know-how—would beget something as wondrous as Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life. Yet, it did. The world-changing evolution from that Point A, one shot of only fifty seconds in length (though apparently L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat was not programmed as part of their inaugural demonstrations—the tale of cinema, as always, exists at the meeting place of science and myth), to Malick’s Point B, weighing in at around 8,280 seconds with hundreds of discrete shots, has been considerable. We take it for granted somewhat that, especially since the advent of sound, how cinema works has been consistent, immutable. However, the countless New Waves, dead ends, discarded technologies, and breakthroughs we’ve seen since 1895 attest to a pliable medium always in flux, even if the meaningful changes may not be apparent at the moment they occur.

Though separated by over a century of cinema, L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat and The Tree of Life share a fundamental sense of wonder: at the image, at the world, at the fact that we are able to capture pieces of its beauty in images. The more things change, the more some things stay the same. The Lumières couldn’t know their single-shot story would grow into Malick’s radical, flowering montage, but neither would a Precambrian single-celled microorganism have predicted it would grow to be a dinosaur, a fish, a tree, or Terrence Malick. The beauty of evolution lies in its mystery—we can only witness how it unfolds in retrospect, making our position within Darwin’s Tree of Life no more privileged than any other.

Appropriately, Malick’s work—not only named after the fourth chapter of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and its famous tree-shaped sketch representing the fundamental law of nature the English naturalist would be the first to describe but also infused with and devoted to its spirit—takes place in hindsight. Jack O’Brien (Sean Penn), as uneasy in his skin as Malick seems to be behind the lens when shooting the glass offices in which Jack works as an architect in modern day Houston (Malick’s always looked to the past for his stories and seems both nervous and awed at the sights of the contemporary world), recollects on the tree of his own personal evolution. His sun-dappled memories of growing up the eldest of three in Waco, Texas (like Malick), may form the bulk of a work that comfortably spans time, but The Tree of Life isn’t mere memory play. Jack’s childhood is framed as one small part of a truly universal story. (Tellingly, the film doesn’t even open on our hero, instead starting with another beginning: a childhood recollection of his mother’s.) It isn’t long after we’ve met him that Malick flashes back to the beginning of his story: not birth, or conception, or his parents’ first meeting, but the Big Bang.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment