by Melissa Anne-Marie Curley

Journal of Religion and Film

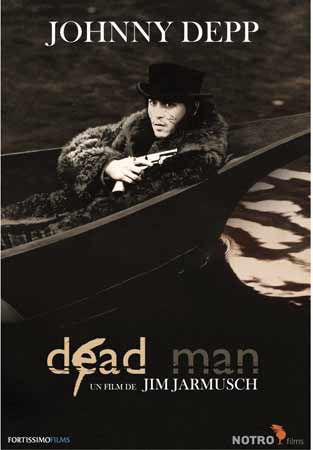

[1] In 1995, American auteur Jim Jarmusch released his experimental western Dead Man. In 1999, Jarmusch released Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai, which played with the genres of the samurai picture and the mafia movie. In this paper, I argue that these two films share a single narrative, and that narrative is about books and what books can do. Taking up Mircea Eliade’s notion of the sacred text as a manual for recovering primordial time, I suggest that the protagonists of both films should be understood as Eliade’s “religious man.”

[2] Ghost Dog is a spectacularly cool black hitman loosely associated with the fading Vargo mafia family—Louie, a lesser member, once saved his life and since then he has served Louie as a retainer, adhering strictly to the rules of the samurai code. The film begins with Ghost Dog botching a job involving Louise Vargo, the daughter of the head of the family; a hit is thus ordered on Ghost Dog himself. The rest of the film traces him as he engineers his inevitable death in such a way that he can be killed both by and for Louie. The dead man in Dead Man is a spectacularly uncool white accountant named William Blake who, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, moves west to the town of Machine, only to find that the job promised him by a Mr. Dickinson has been given away. Through a series of misadventures, Blake ends up getting shot by Dickinson’s son; Blake kills the son in self-defense, Dickinson Sr. places a bounty on his head, and the rest of the film follows him on the run through the badlands, until finally he reaches the water and is set adrift in a boat to die.

[3] These narrative differences demand, naturally, that Dead Man and Ghost Dog exist in different aesthetic universes: one is set in a fin-de-siècle American West and the other in postmodern New York City; one was shot in black and white and the other in color; one was scored by Neil Young and the other by the Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA. Nonetheless, it is easy to compare Dead Man and Ghost Dog. They’re both genre movies and these particular genres have a special family resemblance.1 And despite the distance in terms of historical and geographical location, they also exist in the same narrative universe; Jarmusch tells us this by having the same character appear in both. In Dead Man, he has a lead role—Gary Farmer plays Nobody, a Plains Indian who guides the film’s protagonist through hell, despite his antipathy towards “stupid fucking white men.” In Ghost Dog, he has a cameo—Farmer plays a pigeon keeper who gets just one line: “stupid fucking white men.” Stay through the credits and you find that here too the character’s name is Nobody.

[4] I want to claim though that the two movies are not just comparable—Jarmusch has in fact made the same movie twice. Ghost Dog is, according to the samurai code, committed to live as one already dead; from the first scene then, he is a dead man. Dead Man too has a protagonist who is dead from the outset although we don’t learn this until the end. The film opens with Blake on a train; the train fireman asks him “doesn’t this remind you of when you were in the boat?”—if, in other words, it reminds him of the last scene of the movie, when he dies. So both movies have protagonists who, while appearing to be alive, are already dead; both these dead men are sentenced to death by their employers; and both are occupied with writing what Jarmusch in each case refers to as poetry—a “poetry of war” or a poetry “written in blood.” This poetry is in neither case original: our heroes are tasked with recirculating old texts, not with generating new ones.

[5] Jarmusch himself has old texts circulate through both movies, as props, plot points, and interstitial titles. Gregory Salyer reads Dead Man as exposing the American fear of inauthenticity; in Dead Man, he suggests, “writing is the primary medium for disseminating lies.”2 I would suggest that since Jarmusch himself is a writer—a disseminator of lies—he is also, in these films, exploring the possibility that the lies of the written text can be appropriated in such a way that the reader’s performance turns them into the truth. There are for Jarmusch always two levels to the book: the book as it is located historically and the book as it is appropriated by his heroes. The effect of each appropriation is to disrupt historical time. Acting out the demands of old books becomes then, for Ghost Dog and Blake, a way to refuse their historical locations and force a return to the primordial. Mircea Eliade has famously suggested that “religious man refuses to live solely in what, in modern terms, is called the historical present; he attempts to regain a sacred time”3 through the reenactment of sacred texts. I will argue that the protagonists of Ghost Dog and Dead Men should be understood on these terms as religious men, working with sacred texts, despite the fact that, as we will see, none of the books they read are part of any standard religious canon.

[6] There are two Japanese texts circulating in Ghost Dog: Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure and Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s Rashōmon and Other Stories . Rashōmon serves as Ghost Dog’s linking text. Inside the space of the film, the book links Ghost Dog to the two women in the movie, and the two women to each other. Louise Vargo gives the book to Ghost Dog just after he mistakenly shoots her boyfriend in front of her, telling him “ancient Japan was a pretty strange place”; he gives it to Pearline, a young girl who introduces herself to him in the park, as an initiatory gesture of friendship; and at the end of the movie, Pearline returns it to Ghost Dog. He gives it to Louie before he dies; Louise retrieves it from Louie, covered in blood. The physical object of Rashōmon is thus the sign of the continuing blood relationship between the Vargo family and its heir, Louise, and Ghost Dog and his heir, Pearline. Outside the space of the film, the book links Jarmusch’s movie to Akira Kurosawa’s famous adaptation of Rashōmon.4 Ryōko Otomo points out that the stories collected in Rashōmon are modern re-workings of legends from the classical period, “a product of eclecticism”5 —Akutagawa’s book and Kurosawa’s adaptation both problematize the notion of singular ownership of a text. What Rashōmon signals inside and outside the film then is that texts are not stable; texts circulate and because of this circulation they are at once elusive and open to appropriation. Otomo argues that for Jarmusch Rashōmon and the Hagakure function as “couriers of the true”: the “film pretends as if there were the hidden sacred true, and as if words/languages/texts carried it within.”6 I break with her reading here. “Yabu no naka,” the story to which Jarmusch links his movie, is precisely about the way that a story produces multiple truths in the telling. Texts are for Jarmusch not containers of truth, but props in the performance that produces truth.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment