"My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel--it is, above all, to make you see." -- Joseph Conrad (1897)

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Friday, January 27, 2012

Law and Disorder Radio -- Jon Burge, Former Chicago Police Commander Sentenced to 4 ½ Years; Bill Goodman: State of Democratic Rights; Sara Hogarth: Post Coup Aftermath – Honduras

Law and Disorder Radio (WBAI: New York City)

Jon Burge, Former Chicago Police Commander Sentenced to 4 ½ Years

Here on Law and Disorder we’ve reported on the ongoing developments of the Chicago Torture case and former Chicago police commander Jon Burge. Burge has been sentenced to 4 and a half years in prison for obstruction of justice and lying about torturing prisoners to obtain coerced confessions. The People’s Law Office brought the case in 2005 and the city of Chicago refused to settle while pumping hundreds of thousands of dollars into the case. Attorney with the People’s Law Office Flint Taylor says the city has spent over the 10 million dollars in aiding the defense of former Commander Jon Burge. Mr. Burge, who is 63 and in ill health, was fired from the Chicago Police Department in 1993. Attorney Flint Taylor’s Statement on Burge sentencing.

Guest – Attorney Flint Taylor, a graduate of Brown University and Northwestern University School of Law and a founding partner of the Peoples Law Office. More bio

—-

State of Democratic Rights – Bill Goodman

We’re joined today by attorney Bill Goodman former legal director for the Center for Constitutional Rights. Bill has been an extraordinary public interest lawyer for more than 30 years he’s served as counsel on issues including post-Katrina social justice, public housing, voting rights, the death penalty, living wage and human rights work in Haiti. Bill delivered a speech recently titled the State of Democratic Rights, defining democracy as we now understand it. Everyone of these defining points has been attacked or undermined and very little has been done to repair them under the Obama Administration.

Guest – Bill Goodman, former legal director for the Center for Constitutional Rights has been an extraordinary public interest lawyer for over 30 years, and has served as counsel on issues including post-Katrina social justice, public housing, voting rights, the death penalty, living wage, civil liberties, educational reform, constitutional rights, human rights work in Haiti, and civil disobedience.

—

Post Coup Aftermath – Honduras: Sarah Hogarth

Today we are joined by legal worker Sarah Hogarth who has recently returned from a human rights delegation to Honduras through the Friendship Office of the Americas. We talk with her about her observations on the post coup human rights crisis in that country. As listeners may know On June 28, 2009, the Honduran military ousted the democratically elected President Manuel Zelaya. Former Parliamentary speaker Roberto Micheletti was sworn in as Zelaya’s replacement. Repressive tactics were used immediately after the coup–people on the front lines who oppose this regime have been beaten and illegally detained by the state. Journalists and LGBT activists were among the first to be targeted and killed. Dr James Cockcroft joins interview.

Guest – Sarah Hogarth, human rights activist in New York City. She is a freelance legal worker and writer and has recently returned from a human rights delegation to Honduras through the Friendship Office of the Americas. The delegation met with activists to learn about the human rights situation in Honduras in the one year since the elections in November 2009. In June 2009, democratically elected President of Honduras, Manuel Zelaya, was removed in a military coup d’etat.

Guest – Dr. James Cockcroft, historian and activist, Jim has written 45 books on Latin America. He’s a professor at the State University of New York and is a member of the International Committee for the Freedom of the Cuban Five.

To Listen to the Episode

Jon Burge, Former Chicago Police Commander Sentenced to 4 ½ Years

Here on Law and Disorder we’ve reported on the ongoing developments of the Chicago Torture case and former Chicago police commander Jon Burge. Burge has been sentenced to 4 and a half years in prison for obstruction of justice and lying about torturing prisoners to obtain coerced confessions. The People’s Law Office brought the case in 2005 and the city of Chicago refused to settle while pumping hundreds of thousands of dollars into the case. Attorney with the People’s Law Office Flint Taylor says the city has spent over the 10 million dollars in aiding the defense of former Commander Jon Burge. Mr. Burge, who is 63 and in ill health, was fired from the Chicago Police Department in 1993. Attorney Flint Taylor’s Statement on Burge sentencing.

Guest – Attorney Flint Taylor, a graduate of Brown University and Northwestern University School of Law and a founding partner of the Peoples Law Office. More bio

—-

State of Democratic Rights – Bill Goodman

We’re joined today by attorney Bill Goodman former legal director for the Center for Constitutional Rights. Bill has been an extraordinary public interest lawyer for more than 30 years he’s served as counsel on issues including post-Katrina social justice, public housing, voting rights, the death penalty, living wage and human rights work in Haiti. Bill delivered a speech recently titled the State of Democratic Rights, defining democracy as we now understand it. Everyone of these defining points has been attacked or undermined and very little has been done to repair them under the Obama Administration.

Guest – Bill Goodman, former legal director for the Center for Constitutional Rights has been an extraordinary public interest lawyer for over 30 years, and has served as counsel on issues including post-Katrina social justice, public housing, voting rights, the death penalty, living wage, civil liberties, educational reform, constitutional rights, human rights work in Haiti, and civil disobedience.

—

Post Coup Aftermath – Honduras: Sarah Hogarth

Today we are joined by legal worker Sarah Hogarth who has recently returned from a human rights delegation to Honduras through the Friendship Office of the Americas. We talk with her about her observations on the post coup human rights crisis in that country. As listeners may know On June 28, 2009, the Honduran military ousted the democratically elected President Manuel Zelaya. Former Parliamentary speaker Roberto Micheletti was sworn in as Zelaya’s replacement. Repressive tactics were used immediately after the coup–people on the front lines who oppose this regime have been beaten and illegally detained by the state. Journalists and LGBT activists were among the first to be targeted and killed. Dr James Cockcroft joins interview.

Guest – Sarah Hogarth, human rights activist in New York City. She is a freelance legal worker and writer and has recently returned from a human rights delegation to Honduras through the Friendship Office of the Americas. The delegation met with activists to learn about the human rights situation in Honduras in the one year since the elections in November 2009. In June 2009, democratically elected President of Honduras, Manuel Zelaya, was removed in a military coup d’etat.

Guest – Dr. James Cockcroft, historian and activist, Jim has written 45 books on Latin America. He’s a professor at the State University of New York and is a member of the International Committee for the Freedom of the Cuban Five.

To Listen to the Episode

Claudia Springer: Taken by Muslims -- Captivity Narratives in The Lives of a Bengal Lancer and Prisoner of the Mountains

Taken by Muslims: captivity narratives in The Lives of a Bengal Lancer

and Prisoner of the Mountains

by Claudia Springer

Jump Cut

Prisoner of the Mountains does not simply reverse the terms of typical Muslim captivity narratives and naively assert that all Russians are destructive and all Chechens are kindhearted. Quite the contrary: there are trigger-happy Chechens eager to kill the two captive soldiers, and a Chechen man shoots his own son for the offense of working for the Russian police. Their violence, though, is shown in the context of their motivations, not as resulting from sadistic impulses. On the Russian side, even the Commander seems to have a change of heart and indicates that he may be ready to trade Abdoul-Mourat's son, an event that is foiled when the son tries to escape and is shot. Rather than paint a simplistic picture, the film suggests that empathy becomes possible when people learn about the realities of others' lives.

In Vanya's friendship with Dina, we see the film reject Orientalist divisiveness and replace it with what philosopher Martin Buber calls an "I and thou" relationship based on nonjudgmental respect. Vanya and Dina overcome inherited cultural myths that would make them enemies and learn to perceive each other as individuals, not symbols. This is the type of connection called for by Czech theorist Vilém Flusser, who critiques the insularity of people who identify too strongly with their homelands—their heimats—to the point that they reject foreigners and anyone with unfamiliar customs. Flusser offers as a solution to intolerance the condition of the migrant, a person who is not anchored to any one place and who "carries in his unconscious bits and pieces of the mysteries of all the heimats through which he has wandered" (14). The migrant, Flusser writes, works on "the mystery of living together with others" and poses the following challenge to all of us:

"how can I overcome the prejudices of the bits and pieces of mysteries that reside within me, and how can I break through the prejudices that are anchored in the mysteries of others, so that together with them we may create something beautiful out of something that is ugly?" (15).

Prisoner of the Mountains gives us a glimpse of two people—Vanya and Dina—who break through prejudices and briefly create something beautiful. Their friendship develops awkwardly and tentatively, initiated by curiosity and followed by small acts of generosity, leading up to her secret visits to the deep pit within which Vanya is chained after his failed attempt to escape with Sacha. In addition to lowering bread and water to him on a rope, Dina informs him of his fate, standing above him at the edge of the pit: "My brother is dead. You have one more night to live." Her elevation indicates her power over him, but their conversation reveals mutual respect, she by acknowledging that he has a right to know what lies ahead, and he by responding patiently. Their cultural differences are apparent, because her idea of being helpful originates in her beliefs about the afterlife, which are meaningless to him, but his responses, while indicating his despair, avoid undermining her. She says, "Usually they throw the enemies' bodies to the jackals. But I will bury yours." He asks her to bring the key to release him. She says, "No. I will dig a wide grave for you. And you will see the Angel of Death. I'll put my necklace in the grave as your wedding gift. Maybe your soul will find a bride in heaven." He responds with a gentle smile: "I don't think so."

Later, she does bring him the key to his leg shackle after finding it hidden in a box while the film crosscuts to her father returning to the village with his son's body in the back of a truck. Before she throws the key to Vanya, she says to him, "Don't kill any more people, promise?" Her request represents a significant shift away from her former acculturated hatred for Russians as well as an attempt to break the cycle of revenge that has trapped both sides in the conflict. She has learned through her friendship with Vanya to respect life—everyone's life. Vanya responds in kind when he refuses to leave in order to protect her from punishment. Her father, Abdoul-Mourat, finds the two of them together at the edge of the pit and sends her home after scolding her for being more concerned about Vanya than about her own dead brother. But even Abdoul-Mourat—perhaps following his daughter's example—rejects vengeance when he lets Vanya go after marching him into the mountains.

Vanya's respect for Dina extends to the film's refusal to eroticize her. Even when she dances for him, she is not objectified; her dance is grave and earnest and shot from a respectful distance. She wears a headscarf and boots and an ankle-length red dress with a dark jacket. Her dance is accompanied by wailing diegetic music from a funeral procession winding its way through the village. She and the other Chechen women—most of them weather-beaten and wearing headscarves—are frequently seen at work. It is their labor, not their sexuality, that defines them. Dina is seen working with donkeys, preparing food, cleaning up, knitting—preparing for life as a village woman—and she calmly explains her future to Vanya before she dances for him. He asks her, "Did you get married yet?" She replies, "No." He says, "I would marry you." She says, "We cannot get married. I can get married next year. We marry early here." Later, when she returns to the pit to tell Vanya that he has one more night to live, she is dressed entirely in black to show that she is in mourning for her brother but also suggesting that she is preparing to mourn for Vanya, taking on the role of his widow although they have never even exchanged a kiss. She stands above him in her black robe, embodying the Angel of Death as well as the bride she speculates he might find in the afterlife. Their union is symbolic, impossible in the world they inhabit but indicative of the connection they have made.

The film also treats the Chechen landscape, customs, and music, all initially strange and unfamiliar to the Russian captives, with respect. Perched on rocky cliffs, the village is both precarious and solid, built of stone to withstand the ferocious winds. A song sung by the village children tells of the longevity of the Chechen culture and the inability of visitors to tolerate the wind. The film was shot on location in the Russian Republic of Dagestan, neighboring Chechnya, just twenty miles from where fighting was taking place at the time. (Ironically and sadly, the region's harsh conditions proved fatal for the actor Sergei Bodrov Jr. a few years later when he returned to direct a film and was killed by an avalanche.) The music, cinematography, and editing combine to emphasize endurance. But it is all obliterated at the end with the offscreen Russian assault. Vanya's inability to conjure up the villagers in his dreams symbolizes the military attack's total erasure of their existence, eliminating their history along with their future. Instead of exalting military might—as does The Lives of a Bengal Lancer—the film raises questions about the morality of bombing raids on civilian targets as a military strategy.

The final crucial element that sets this film apart is its slow, deliberate pacing, counteracting the speed with which the Bengal Lancers engage in their adventures. Unhurried panning shots linger over the mountains and valleys and the village's worn cobblestone streets. It takes time to overcome enmity, and Prisoner of the Mountains measures time very slowly. Its choices provide a cinematic model for relinquishing Hollywood's tired anti-Muslim clichés.[2]

To Read the Entire Essay

__PrisonerOfTheMountains(3).jpg)

and Prisoner of the Mountains

by Claudia Springer

Jump Cut

Prisoner of the Mountains does not simply reverse the terms of typical Muslim captivity narratives and naively assert that all Russians are destructive and all Chechens are kindhearted. Quite the contrary: there are trigger-happy Chechens eager to kill the two captive soldiers, and a Chechen man shoots his own son for the offense of working for the Russian police. Their violence, though, is shown in the context of their motivations, not as resulting from sadistic impulses. On the Russian side, even the Commander seems to have a change of heart and indicates that he may be ready to trade Abdoul-Mourat's son, an event that is foiled when the son tries to escape and is shot. Rather than paint a simplistic picture, the film suggests that empathy becomes possible when people learn about the realities of others' lives.

In Vanya's friendship with Dina, we see the film reject Orientalist divisiveness and replace it with what philosopher Martin Buber calls an "I and thou" relationship based on nonjudgmental respect. Vanya and Dina overcome inherited cultural myths that would make them enemies and learn to perceive each other as individuals, not symbols. This is the type of connection called for by Czech theorist Vilém Flusser, who critiques the insularity of people who identify too strongly with their homelands—their heimats—to the point that they reject foreigners and anyone with unfamiliar customs. Flusser offers as a solution to intolerance the condition of the migrant, a person who is not anchored to any one place and who "carries in his unconscious bits and pieces of the mysteries of all the heimats through which he has wandered" (14). The migrant, Flusser writes, works on "the mystery of living together with others" and poses the following challenge to all of us:

"how can I overcome the prejudices of the bits and pieces of mysteries that reside within me, and how can I break through the prejudices that are anchored in the mysteries of others, so that together with them we may create something beautiful out of something that is ugly?" (15).

Prisoner of the Mountains gives us a glimpse of two people—Vanya and Dina—who break through prejudices and briefly create something beautiful. Their friendship develops awkwardly and tentatively, initiated by curiosity and followed by small acts of generosity, leading up to her secret visits to the deep pit within which Vanya is chained after his failed attempt to escape with Sacha. In addition to lowering bread and water to him on a rope, Dina informs him of his fate, standing above him at the edge of the pit: "My brother is dead. You have one more night to live." Her elevation indicates her power over him, but their conversation reveals mutual respect, she by acknowledging that he has a right to know what lies ahead, and he by responding patiently. Their cultural differences are apparent, because her idea of being helpful originates in her beliefs about the afterlife, which are meaningless to him, but his responses, while indicating his despair, avoid undermining her. She says, "Usually they throw the enemies' bodies to the jackals. But I will bury yours." He asks her to bring the key to release him. She says, "No. I will dig a wide grave for you. And you will see the Angel of Death. I'll put my necklace in the grave as your wedding gift. Maybe your soul will find a bride in heaven." He responds with a gentle smile: "I don't think so."

Later, she does bring him the key to his leg shackle after finding it hidden in a box while the film crosscuts to her father returning to the village with his son's body in the back of a truck. Before she throws the key to Vanya, she says to him, "Don't kill any more people, promise?" Her request represents a significant shift away from her former acculturated hatred for Russians as well as an attempt to break the cycle of revenge that has trapped both sides in the conflict. She has learned through her friendship with Vanya to respect life—everyone's life. Vanya responds in kind when he refuses to leave in order to protect her from punishment. Her father, Abdoul-Mourat, finds the two of them together at the edge of the pit and sends her home after scolding her for being more concerned about Vanya than about her own dead brother. But even Abdoul-Mourat—perhaps following his daughter's example—rejects vengeance when he lets Vanya go after marching him into the mountains.

Vanya's respect for Dina extends to the film's refusal to eroticize her. Even when she dances for him, she is not objectified; her dance is grave and earnest and shot from a respectful distance. She wears a headscarf and boots and an ankle-length red dress with a dark jacket. Her dance is accompanied by wailing diegetic music from a funeral procession winding its way through the village. She and the other Chechen women—most of them weather-beaten and wearing headscarves—are frequently seen at work. It is their labor, not their sexuality, that defines them. Dina is seen working with donkeys, preparing food, cleaning up, knitting—preparing for life as a village woman—and she calmly explains her future to Vanya before she dances for him. He asks her, "Did you get married yet?" She replies, "No." He says, "I would marry you." She says, "We cannot get married. I can get married next year. We marry early here." Later, when she returns to the pit to tell Vanya that he has one more night to live, she is dressed entirely in black to show that she is in mourning for her brother but also suggesting that she is preparing to mourn for Vanya, taking on the role of his widow although they have never even exchanged a kiss. She stands above him in her black robe, embodying the Angel of Death as well as the bride she speculates he might find in the afterlife. Their union is symbolic, impossible in the world they inhabit but indicative of the connection they have made.

The film also treats the Chechen landscape, customs, and music, all initially strange and unfamiliar to the Russian captives, with respect. Perched on rocky cliffs, the village is both precarious and solid, built of stone to withstand the ferocious winds. A song sung by the village children tells of the longevity of the Chechen culture and the inability of visitors to tolerate the wind. The film was shot on location in the Russian Republic of Dagestan, neighboring Chechnya, just twenty miles from where fighting was taking place at the time. (Ironically and sadly, the region's harsh conditions proved fatal for the actor Sergei Bodrov Jr. a few years later when he returned to direct a film and was killed by an avalanche.) The music, cinematography, and editing combine to emphasize endurance. But it is all obliterated at the end with the offscreen Russian assault. Vanya's inability to conjure up the villagers in his dreams symbolizes the military attack's total erasure of their existence, eliminating their history along with their future. Instead of exalting military might—as does The Lives of a Bengal Lancer—the film raises questions about the morality of bombing raids on civilian targets as a military strategy.

The final crucial element that sets this film apart is its slow, deliberate pacing, counteracting the speed with which the Bengal Lancers engage in their adventures. Unhurried panning shots linger over the mountains and valleys and the village's worn cobblestone streets. It takes time to overcome enmity, and Prisoner of the Mountains measures time very slowly. Its choices provide a cinematic model for relinquishing Hollywood's tired anti-Muslim clichés.[2]

To Read the Entire Essay

__PrisonerOfTheMountains(3).jpg)

Thursday, January 26, 2012

Open Culture: Alain de Botton Wants a Religion for Atheists -- Introducing Atheism 2.0

Alain de Botton Wants a Religion for Atheists: Introducing Atheism 2.0

Open Culture

Last summer Alain de Botton, one of the better popularizers of philosophy, appeared at TEDGlobal and called for a new kind of atheism. An Atheism 2.0. This revised atheism would let atheists deny a creator and yet not forsake all the other good things religion can offer — tradition, ritual, community, insights into living a good life, the ability to experience transcendence, taking part in institutions that can change the world, and the rest.

What he’s describing kind of sounds like what already happens in the Unitarian Church … or The School of Life, a London-based institution founded by de Botton in 2008. The school offers courses “in the important questions of everyday life” and also hosts Sunday Sermons that feature “maverick cultural figures” talking about important principles to live by. Click here and you can watch several past sermons presented by actress Miranda July, physicist Lawrence Krauss, author Rebecca Solnit, and Alain de Botton himself.

If Atheism 2.0 piques your interest, you’ll want to pre-order de Botton’s soon-to-be-published book, Religion for Atheists: A Non-Believer’s Guide to the Uses of Religion.

Link

Open Culture

Last summer Alain de Botton, one of the better popularizers of philosophy, appeared at TEDGlobal and called for a new kind of atheism. An Atheism 2.0. This revised atheism would let atheists deny a creator and yet not forsake all the other good things religion can offer — tradition, ritual, community, insights into living a good life, the ability to experience transcendence, taking part in institutions that can change the world, and the rest.

What he’s describing kind of sounds like what already happens in the Unitarian Church … or The School of Life, a London-based institution founded by de Botton in 2008. The school offers courses “in the important questions of everyday life” and also hosts Sunday Sermons that feature “maverick cultural figures” talking about important principles to live by. Click here and you can watch several past sermons presented by actress Miranda July, physicist Lawrence Krauss, author Rebecca Solnit, and Alain de Botton himself.

If Atheism 2.0 piques your interest, you’ll want to pre-order de Botton’s soon-to-be-published book, Religion for Atheists: A Non-Believer’s Guide to the Uses of Religion.

Link

Dan Ariely: The Upside of Irrationality

Dan Ariely: The Upside of Irrationality

FORA TV

Dan Ariely is the Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Behavioral Economics at MIT Sloan School of Management. He also holds an appointment at the MIT Media Lab where he is the head of the eRationality research group.

He is considered to be one of the leading behavioral economists. Currently, Ariely is serving as a Visiting Professor at the Duke University, Fuqua School of Business where he is teaching a course based upon his findings in Predictably Irrational.

Ariely was an undergraduate at Tel Aviv University and received a Ph.D. and M.A. in cognitive psychology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and a Ph.D. in business from Duke University. His research focuses on discovering and measuring how people make decisions. He models the human decision making process and in particular the irrational decisions that we all make every day.

Ariely is the author of the book Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions

FORA TV

Dan Ariely is the Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Behavioral Economics at MIT Sloan School of Management. He also holds an appointment at the MIT Media Lab where he is the head of the eRationality research group.

He is considered to be one of the leading behavioral economists. Currently, Ariely is serving as a Visiting Professor at the Duke University, Fuqua School of Business where he is teaching a course based upon his findings in Predictably Irrational.

Ariely was an undergraduate at Tel Aviv University and received a Ph.D. and M.A. in cognitive psychology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and a Ph.D. in business from Duke University. His research focuses on discovering and measuring how people make decisions. He models the human decision making process and in particular the irrational decisions that we all make every day.

Ariely is the author of the book Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions

Dan Ariely: The Upside of Irrationality from Booksmith on FORA.tv

Monday, January 23, 2012

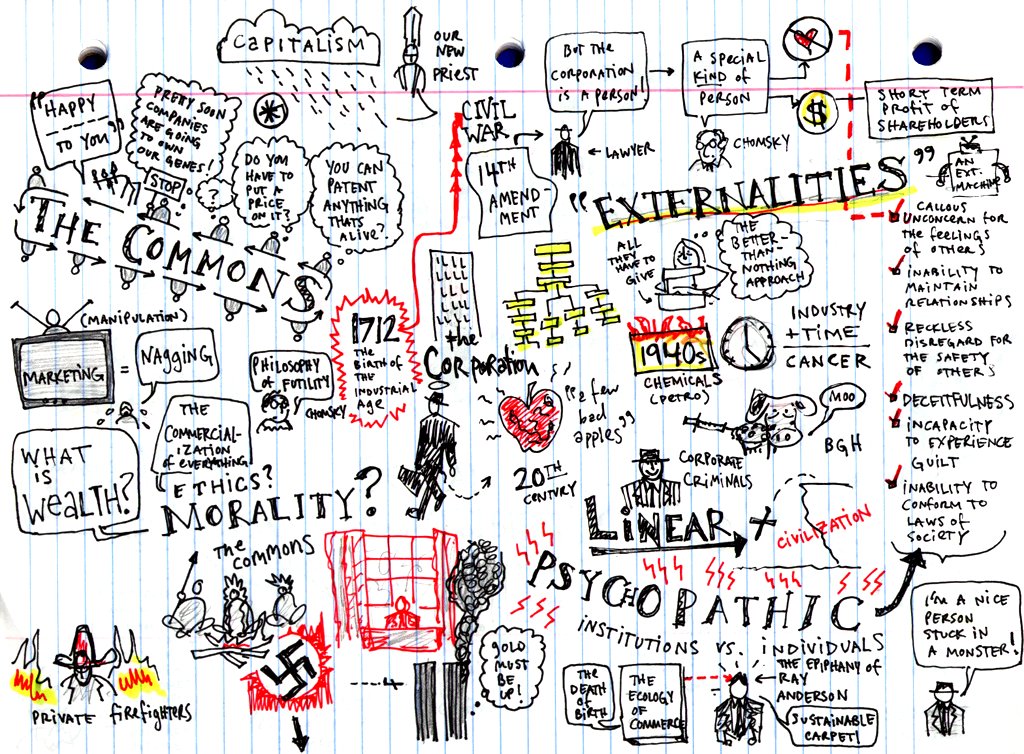

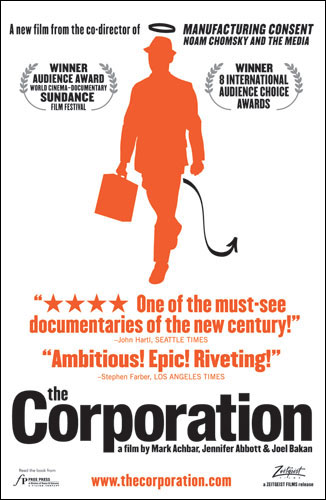

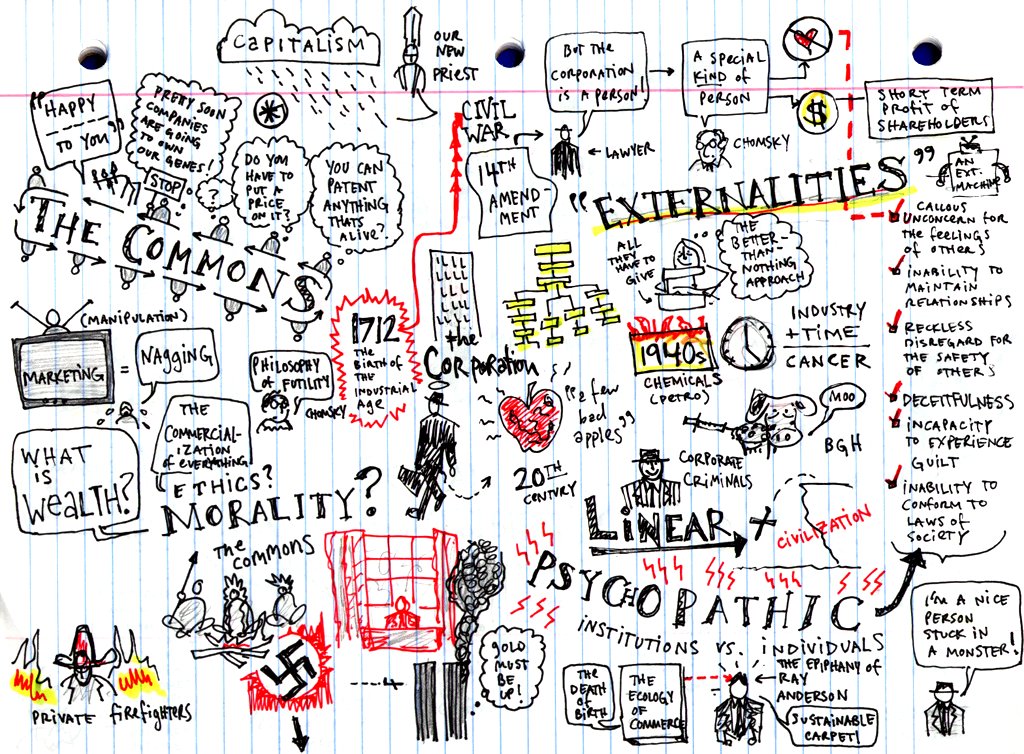

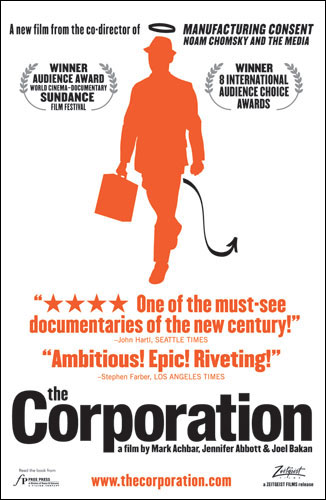

The Corporation (Canada: Mark Achbar, Jennifer Abbott and Joel Balkan, 2003/2005)

[ENG 102 students this is the post for the class screening of The Corporation -- in the comments below this post, feel free to ask questions, provide responses, or introduce information]

The People Featured in The Corporation

The Official Website

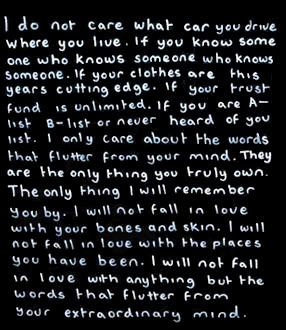

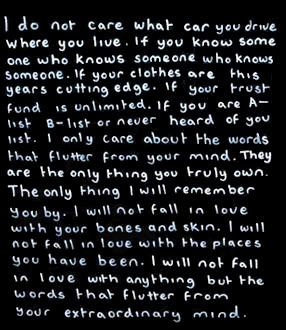

Image by Austin Kleon

To Watch The Corporation (with commercials) online

The People Featured in The Corporation

The Official Website

Image by Austin Kleon

To Watch The Corporation (with commercials) online

Sunday, January 22, 2012

Left, Right and Center: Third Party Politics/Remembering Tony Blankley

(Dialogic is very sorry to hear that conservative critic and long time Left, Right & Center co-host Tony Blankley died recently. To hear the shows memories about/of Tony check out their episode Remembering Tony Blankley)

Third Party Politics

Left, Right & Center (KCRW: Santa Monica, CA)

Does America need a third political party? The backlash against Obama on the left and the tepid support for Romney (the "anyone but Romney” vote has gone from Bachmann to Perry to Cain to Gingrich...) would seem to make this a fine time for an independent party to emerge. But it's also the year of $1 billion campaigns and Citizens United funding schemes. Indeed, the only grass roots getting fed by cash are Republican friendly Tea Partiers. Aren't they an example of just how strong a stranglehold the two party system has on American politics?

To Listen to the Episode

Third Party Politics

Left, Right & Center (KCRW: Santa Monica, CA)

Does America need a third political party? The backlash against Obama on the left and the tepid support for Romney (the "anyone but Romney” vote has gone from Bachmann to Perry to Cain to Gingrich...) would seem to make this a fine time for an independent party to emerge. But it's also the year of $1 billion campaigns and Citizens United funding schemes. Indeed, the only grass roots getting fed by cash are Republican friendly Tea Partiers. Aren't they an example of just how strong a stranglehold the two party system has on American politics?

To Listen to the Episode

Saturday, January 21, 2012

Raj Patel: Feeding Ten Billion

Feeding Ten Billion

Ideas (CBC: Canada)

The world just got its seven billionth citizen, and the population explosion shows no signs of stopping. In a Saskatoon lecture, writer and activist Raj Patel argues that the only way to feed everyone is to completely rethink agriculture.

To Listen to the Episode

Ideas (CBC: Canada)

The world just got its seven billionth citizen, and the population explosion shows no signs of stopping. In a Saskatoon lecture, writer and activist Raj Patel argues that the only way to feed everyone is to completely rethink agriculture.

To Listen to the Episode

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Hassan Ghedi Santur: On Being A Muslim In The West, Part 1 and 2

Ideas (CBC: Canada)

On Being A Muslim In The West, Part 1

Amid continuing tension between Muslim and non-Muslim populations in many western countries, the question keeps coming back: Is Islam compatible with western values? Hassan Ghedi Santur asks if someone can embrace the secular, pluralist democratic values of the West and still be a "good" Muslim?

To Listen to the Episode

On Being A Muslim In The West, Part 2

It is said that there is a struggle for the soul of Islam; a jihad for the hearts and minds of the 1.6 billion people who profess Islam as their faith. Hassan Ghedi Santur explores the intersection between religion, spirituality, and politics in the lives of Muslims, particularly Muslim women. He presents the portrait of an activist, an academic and a writer who are in their own way, changing the face of Islam.

To Listen to the Episode

On Being A Muslim In The West, Part 1

Amid continuing tension between Muslim and non-Muslim populations in many western countries, the question keeps coming back: Is Islam compatible with western values? Hassan Ghedi Santur asks if someone can embrace the secular, pluralist democratic values of the West and still be a "good" Muslim?

To Listen to the Episode

On Being A Muslim In The West, Part 2

It is said that there is a struggle for the soul of Islam; a jihad for the hearts and minds of the 1.6 billion people who profess Islam as their faith. Hassan Ghedi Santur explores the intersection between religion, spirituality, and politics in the lives of Muslims, particularly Muslim women. He presents the portrait of an activist, an academic and a writer who are in their own way, changing the face of Islam.

To Listen to the Episode

John Berger: Why should an artist’s way of looking at the world have any meaning for us?

“Why should an artist’s way of looking at the world have any meaning for us? Why does it give us pleasure? Because, I believe, it increases our awareness of our own potentiality.”

— John Berger, Permanent Red: Essays in Seeing (1960)

— John Berger, Permanent Red: Essays in Seeing (1960)

Wednesday, January 18, 2012

Paul Tassi: PIPA Weakens as SOPA Gets Hypocritical

(via Nathaniel Hall)

PIPA Weakens as SOPA Gets Hypocritical

by Paul Tassi

Forbes

Two internet censorship themed posts in one day today, as the issue is starting to snowball, and the tide almost seems like it might be turning. There’s been a new development about PIPA, the Protect IP bill that is the House version of the Senate’s SOPA initiative.

Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt), who co-authored the bill with Sen .Orin Hatch (R-Utah) has said he is willing to remove the most controversial portion of Protect IP, which would empower courts to demand that ISPs block access to certain foreign sites, effectively censoring them.

Leahy credits his constituents for giving him “insight” into the issue, but it’s also likely he changed his mind because many of the big name ISPs were not in favor of that section of the bill. A similar sort of provision still exists in the Senate’s SOPA however.

The second item of note is that SOPA author Sen. Lamar Smith (R-Tx) has himself been found guilty of violating copyright. The issue at hand is pointed out on VICE.com, where it juxtaposes this screenshot of Smith’s website from before his SOPA days.

To Read the Rest of the Commentary and Access Hyperlinked Resources

PIPA Weakens as SOPA Gets Hypocritical

by Paul Tassi

Forbes

Two internet censorship themed posts in one day today, as the issue is starting to snowball, and the tide almost seems like it might be turning. There’s been a new development about PIPA, the Protect IP bill that is the House version of the Senate’s SOPA initiative.

Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt), who co-authored the bill with Sen .Orin Hatch (R-Utah) has said he is willing to remove the most controversial portion of Protect IP, which would empower courts to demand that ISPs block access to certain foreign sites, effectively censoring them.

Leahy credits his constituents for giving him “insight” into the issue, but it’s also likely he changed his mind because many of the big name ISPs were not in favor of that section of the bill. A similar sort of provision still exists in the Senate’s SOPA however.

The second item of note is that SOPA author Sen. Lamar Smith (R-Tx) has himself been found guilty of violating copyright. The issue at hand is pointed out on VICE.com, where it juxtaposes this screenshot of Smith’s website from before his SOPA days.

To Read the Rest of the Commentary and Access Hyperlinked Resources

Robert Alpert: The Social Network - The Contemporary Pursuit of Happiness through Social Connections

The Social Network: the contemporary pursuit of happiness through social connections

by Robert Alpert

Jump Cut

The United States’ myth of opportunity holds that those who work hard may achieve, and that history is a progressive, forward movement in which the country betters itself through such hard work. Yet such optimism has consistently been tempered by a sense that “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” inadequately define a satisfied life. Thus, the myth of individual success also frequently becomes a story about loss and failure. For example, based on the life of William Randolph Hearst, the owner of a nationwide chain of “yellow journalism” newspapers, Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) portrays Charles Foster Kane as having achieved material success at the cost of a life of dissatisfaction. Forcibly exiled from his childhood home, he remains consistently angry and alone as an adult. Even that champion of historical progress, John Ford, late in life enunciated the myth’s failure in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” grandly announces the newspaper editor. The successful lawyer, governor, senator and ambassador to Britain, played by James Stewart, is ashen-faced, however, when he realizes that the material progress he has cultivated on behalf of his country has masked the fact that Vera Miles, the love of his life whom he married, has never loved him. The myth maker Ford eulogizes instead the primitive John Wayne who has died penniless and alone in order to make way for that dream of “progress.”

This same disillusionment also runs through U.S. literature. For example, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) is the story of Jay Gatsby, who believed in the myth of achieving material success and thereby the promise of a better future only to learn the futility of his quest and his loss of a more Edenic past. Thus, the novel concludes:

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter — tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther…And one fine morning — So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”[2]

The Social Network deals with that myth of material success and an historical shift in values in which that myth has come to be accepted as fact. It is a bleak portrayal of a male, adolescent-dominated world in which connections, not relationships, are all. The director, David Fincher, has worked with different screenwriters on all of his movies, and his movies prior to The Social Network — such as Se7en (1995), The Game (1997), Fight Club (1999), Zodiac (2007) and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) — have in common that nearly all have at their center a young man lost and wandering through a series of episodes in which he seeks to define a place for himself. For each of these characters the search is obsessively personal, and in each the character is mistakenly confident that his skills will enable him to triumph. For example, the newly married Brad Pitt as Detective David Mills in Se7en taunts killer Kevin Spacey only to become Spacey’s seventh victim. Michael Douglas, a wealthy financier in The Game, remains certain that he can outsmart those who run the Game only to “succeed” by the grace of those who control the game. Fincher’s characters are lost and angry, adolescents in the bodies of grown men. Even Panic Room (2002), whose main character is played by Jodie Foster, focuses on her illusion that she can acquire security through her ex-husband’s money. Aaron Sorkin, the creator of the TV series West Wing and the screenwriter of The Social Network, places Fincher’s central character in an historical context. As such, he elevates the individual failure of Fincher’s character to a cultural failure.

The Social Network bases its story on Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg), who, while an undergraduate student at Harvard University, developed Facebook. Through deposition testimony in two lawsuits brought against Mark — by Eduardo Savarin (Andrew Garfield) and by the Winkelvoss twins, Cameron and Tyler (both played by Armie Hammer) — the movie recounts how what is today a worldwide phenomenon began in Mark’s dorm room. Like other Fincher characters, Mark is no less brainy, no less confident that he can outsmart those around him, and yet he fails in the end to find any personal satisfaction in his seeming success. The Social Network is especially bleak in that Mark’s personal failure gain him financial rewards in a world in which Facebook is everywhere, including Bosnia where, as a young associate at the law firm defending Mark remarks in disbelief, there are not even any roads.

Mark’s obsessive creation of Facebook results in a worldwide network of “friending,” an exchange of electronic data by persons who are physically and emotionally at a distance from one another. As such, this kind of friending offers a parallel to Mark, who becomes increasingly isolated from those physically surrounding him. Mark Zuckerberg’s contemporary success in business, measured in billions of dollars, results in his personal failure to achieve anything of value. Ironically, it was never about the money for Mark; as a high school student, for example, he uploaded for free his idea of an application for an MP3 player, notwithstanding an offer from Microsoft. Later, in his quest for success, he is oblivious to and uncaring about the consequences to others of his commercial success. As a result, by the end of the film, his success has cost him personal growth, his friendship with his one friend, and the loss of an idealized love of his life. While inventing an online “social network,” Mark is consistently visually framed as a young man alone, whether in his law firm’s large conference room on the night that a settlement will be reached in the two lawsuits or in the loft-like space of the Facebook office on the night Facebook achieves one million members and its entire staff is out celebrating.

The Social Network deals with male adolescents, such as Mark, who should be in transition to manhood but never progress beyond their adolescence. Taught that individual achievement of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” is all, they lack any genuine empathy with others and hence any sense of social obligation or responsibility for its own sake. While Harvard University has long been co-ed, the movie portrays the college as an historic relic: the exclusive domain of its male students. It equates the exclusivity of its “final clubs,” fraternity-like clubs, with the busloads of women brought in by those clubs to Animal House-like parties. Mark’s failed quest was to become a member of a final club at Harvard, which, in Mark’s view, would lead to a “better life,” the contours of which, though, were unknown to him. Likewise, both in Facebook’s early stage when housed in a rented, suburban home in Palo Alto and later when ensconced in its high tech office space, adolescent males run the organization plugged into their computers with women as sexually available and often intoxicated or drugged objects. Women exist solely for the pleasure of these male adolescents who feel nothing beyond themselves and who thereby are inevitably alone in the midst of their noisy, crowded clubs.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by Robert Alpert

Jump Cut

The United States’ myth of opportunity holds that those who work hard may achieve, and that history is a progressive, forward movement in which the country betters itself through such hard work. Yet such optimism has consistently been tempered by a sense that “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” inadequately define a satisfied life. Thus, the myth of individual success also frequently becomes a story about loss and failure. For example, based on the life of William Randolph Hearst, the owner of a nationwide chain of “yellow journalism” newspapers, Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) portrays Charles Foster Kane as having achieved material success at the cost of a life of dissatisfaction. Forcibly exiled from his childhood home, he remains consistently angry and alone as an adult. Even that champion of historical progress, John Ford, late in life enunciated the myth’s failure in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” grandly announces the newspaper editor. The successful lawyer, governor, senator and ambassador to Britain, played by James Stewart, is ashen-faced, however, when he realizes that the material progress he has cultivated on behalf of his country has masked the fact that Vera Miles, the love of his life whom he married, has never loved him. The myth maker Ford eulogizes instead the primitive John Wayne who has died penniless and alone in order to make way for that dream of “progress.”

This same disillusionment also runs through U.S. literature. For example, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) is the story of Jay Gatsby, who believed in the myth of achieving material success and thereby the promise of a better future only to learn the futility of his quest and his loss of a more Edenic past. Thus, the novel concludes:

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter — tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther…And one fine morning — So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”[2]

The Social Network deals with that myth of material success and an historical shift in values in which that myth has come to be accepted as fact. It is a bleak portrayal of a male, adolescent-dominated world in which connections, not relationships, are all. The director, David Fincher, has worked with different screenwriters on all of his movies, and his movies prior to The Social Network — such as Se7en (1995), The Game (1997), Fight Club (1999), Zodiac (2007) and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) — have in common that nearly all have at their center a young man lost and wandering through a series of episodes in which he seeks to define a place for himself. For each of these characters the search is obsessively personal, and in each the character is mistakenly confident that his skills will enable him to triumph. For example, the newly married Brad Pitt as Detective David Mills in Se7en taunts killer Kevin Spacey only to become Spacey’s seventh victim. Michael Douglas, a wealthy financier in The Game, remains certain that he can outsmart those who run the Game only to “succeed” by the grace of those who control the game. Fincher’s characters are lost and angry, adolescents in the bodies of grown men. Even Panic Room (2002), whose main character is played by Jodie Foster, focuses on her illusion that she can acquire security through her ex-husband’s money. Aaron Sorkin, the creator of the TV series West Wing and the screenwriter of The Social Network, places Fincher’s central character in an historical context. As such, he elevates the individual failure of Fincher’s character to a cultural failure.

The Social Network bases its story on Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg), who, while an undergraduate student at Harvard University, developed Facebook. Through deposition testimony in two lawsuits brought against Mark — by Eduardo Savarin (Andrew Garfield) and by the Winkelvoss twins, Cameron and Tyler (both played by Armie Hammer) — the movie recounts how what is today a worldwide phenomenon began in Mark’s dorm room. Like other Fincher characters, Mark is no less brainy, no less confident that he can outsmart those around him, and yet he fails in the end to find any personal satisfaction in his seeming success. The Social Network is especially bleak in that Mark’s personal failure gain him financial rewards in a world in which Facebook is everywhere, including Bosnia where, as a young associate at the law firm defending Mark remarks in disbelief, there are not even any roads.

Mark’s obsessive creation of Facebook results in a worldwide network of “friending,” an exchange of electronic data by persons who are physically and emotionally at a distance from one another. As such, this kind of friending offers a parallel to Mark, who becomes increasingly isolated from those physically surrounding him. Mark Zuckerberg’s contemporary success in business, measured in billions of dollars, results in his personal failure to achieve anything of value. Ironically, it was never about the money for Mark; as a high school student, for example, he uploaded for free his idea of an application for an MP3 player, notwithstanding an offer from Microsoft. Later, in his quest for success, he is oblivious to and uncaring about the consequences to others of his commercial success. As a result, by the end of the film, his success has cost him personal growth, his friendship with his one friend, and the loss of an idealized love of his life. While inventing an online “social network,” Mark is consistently visually framed as a young man alone, whether in his law firm’s large conference room on the night that a settlement will be reached in the two lawsuits or in the loft-like space of the Facebook office on the night Facebook achieves one million members and its entire staff is out celebrating.

The Social Network deals with male adolescents, such as Mark, who should be in transition to manhood but never progress beyond their adolescence. Taught that individual achievement of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” is all, they lack any genuine empathy with others and hence any sense of social obligation or responsibility for its own sake. While Harvard University has long been co-ed, the movie portrays the college as an historic relic: the exclusive domain of its male students. It equates the exclusivity of its “final clubs,” fraternity-like clubs, with the busloads of women brought in by those clubs to Animal House-like parties. Mark’s failed quest was to become a member of a final club at Harvard, which, in Mark’s view, would lead to a “better life,” the contours of which, though, were unknown to him. Likewise, both in Facebook’s early stage when housed in a rented, suburban home in Palo Alto and later when ensconced in its high tech office space, adolescent males run the organization plugged into their computers with women as sexually available and often intoxicated or drugged objects. Women exist solely for the pleasure of these male adolescents who feel nothing beyond themselves and who thereby are inevitably alone in the midst of their noisy, crowded clubs.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Truth/Authenticity: Peace and Conflict Studies Archive

Apodaca, Greg. Greg's Digital Portfolio (Professional website for his digital retouching services with examples of his work: 2012)

"Authenticity." To the Best of Our Knowledge (June 13, 2010)

Bady, Aaron. "Lincoln Against the Radicals." Jacobin (November 26, 2012)

Ball, Norman. "The Power of Auteurs and the Last Man Standing: Adam Curtis' Documentary Nightmares." Bright Lights Film Journal #78 (November 2012)

Benton, Michael. "Review: Exit Through the Gift Shop." North of Center (March 2, 2011)

Billings, Andrew C. "Biographical Omissions: The Case of A Beautiful Mind and the Search For Authenticity." The Film Journal #1 (May 2002)

Curley, Melissa Anne-Marie. "Dead Men Don’t Lie: Sacred Texts in Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man and Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai." Journal Of Religion & Film 12.2 (October 2008)

Daston, Lorraine. "How To Think About Science #2: On Paradigms and Objectivity." Ideas (January 2, 2009)

"The Documentary Real: On the ambiguous relation between documentary film and reality." KASK [Symposium that is recorded in video segments online of all the presentations: October 21, 2010]

Farrow, Robert. "The Wicker Man: Games of truth, anthropology, and the death of ‘man’." Metaphilm (June 20, 2005)

Hastings, Michael. "Army Whistleblower Lt. Col. Daniel Davis Says Pentagon Deceiving Public on Afghan War." Democracy Now (February 15, 2012)

Hedges, Chris. "The Death of Truth." TruthDig (May 5, 2013)

Herzog, Werner and Errol Morris. "The Act of Killing." Vice (Video posted on Youtube: July 17, 2013)

Kilpatrick, Connor. "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down." Jacobin (November 28, 2012)

Measom, Tyler. "Through the Lens: An Honest Liar." Radio West (April 28, 2014) [Documentary on The Amazing Randi]

Menon, Anil. "It's basically a framing problem." (excerpt) The Beast with Nine Billion Feet. Young Zubaan, 2009.

Morris, Errol. "A Wilderness of Errors." On the Media (September 21, 2012)

Phillips, Peter. "Project Censored." Boiling Frogs (June 4, 2010)

Sampson, Benjamin. "Layers of Paradox in F for Fake." Mediascape (Fall 2009)

Shenk, Jon. "Playback: Errol Morris' The Thin Blue Line." Documentary (Summer 2013)

"Straight Outta Chevy Chase." Radiolab (April 1, 2014) ["Over the past 40 years, hip-hop music has gone from underground phenomenon to global commodity. But as The New Yorker's Andrew Marantz explains, massive commercial success is a tightrope walk for any genre of popular music, and especially one built on authenticity and “realness.” Hip-hop constantly runs the risk of becoming a watered-down imitation of its former self - just, you know, pop music. Andrew introduces us to Peter Rosenberg, a guy who takes this doomsday scenario very seriously. Peter is a DJ at Hot 97, New York City’s iconic hip-hop station, and a vocal booster of what he calls “real” hip-hop. But as a Jewish fellow from suburban Maryland, he's also the first to admit that he's an unlikely arbiter for what is and what isn't hip-hop. With the help of Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest and NPR's Frannie Kelley, we explore the strange ways that hip-hop deals with that age-old question: are you in or are you out?"]

"The Surprising History of Gun Control, School Shooting Myths, and More ." On the Media (December 21, 2012)

Tofts, Darren. "In My Time of Dying: The Premature Death of a Film Classic." LOLA #1 (2011)

Tracy, Andrew. "Genuine Class: All the Real Girls and All the Right Moves." Reverse Shot #29 (2011)

Vizcarrondo, Sara. "The Art of 'Killing': How Much Truth Comes from the Lie that Tells the Truth?" Documentary (Summer 2013)

"Authenticity." To the Best of Our Knowledge (June 13, 2010)

Bady, Aaron. "Lincoln Against the Radicals." Jacobin (November 26, 2012)

Ball, Norman. "The Power of Auteurs and the Last Man Standing: Adam Curtis' Documentary Nightmares." Bright Lights Film Journal #78 (November 2012)

Benton, Michael. "Review: Exit Through the Gift Shop." North of Center (March 2, 2011)

Billings, Andrew C. "Biographical Omissions: The Case of A Beautiful Mind and the Search For Authenticity." The Film Journal #1 (May 2002)

Curley, Melissa Anne-Marie. "Dead Men Don’t Lie: Sacred Texts in Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man and Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai." Journal Of Religion & Film 12.2 (October 2008)

Daston, Lorraine. "How To Think About Science #2: On Paradigms and Objectivity." Ideas (January 2, 2009)

"The Documentary Real: On the ambiguous relation between documentary film and reality." KASK [Symposium that is recorded in video segments online of all the presentations: October 21, 2010]

Farrow, Robert. "The Wicker Man: Games of truth, anthropology, and the death of ‘man’." Metaphilm (June 20, 2005)

Hastings, Michael. "Army Whistleblower Lt. Col. Daniel Davis Says Pentagon Deceiving Public on Afghan War." Democracy Now (February 15, 2012)

Hedges, Chris. "The Death of Truth." TruthDig (May 5, 2013)

Herzog, Werner and Errol Morris. "The Act of Killing." Vice (Video posted on Youtube: July 17, 2013)

Kilpatrick, Connor. "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down." Jacobin (November 28, 2012)

Measom, Tyler. "Through the Lens: An Honest Liar." Radio West (April 28, 2014) [Documentary on The Amazing Randi]

Menon, Anil. "It's basically a framing problem." (excerpt) The Beast with Nine Billion Feet. Young Zubaan, 2009.

Morris, Errol. "A Wilderness of Errors." On the Media (September 21, 2012)

Phillips, Peter. "Project Censored." Boiling Frogs (June 4, 2010)

Sampson, Benjamin. "Layers of Paradox in F for Fake." Mediascape (Fall 2009)

Shenk, Jon. "Playback: Errol Morris' The Thin Blue Line." Documentary (Summer 2013)

"Straight Outta Chevy Chase." Radiolab (April 1, 2014) ["Over the past 40 years, hip-hop music has gone from underground phenomenon to global commodity. But as The New Yorker's Andrew Marantz explains, massive commercial success is a tightrope walk for any genre of popular music, and especially one built on authenticity and “realness.” Hip-hop constantly runs the risk of becoming a watered-down imitation of its former self - just, you know, pop music. Andrew introduces us to Peter Rosenberg, a guy who takes this doomsday scenario very seriously. Peter is a DJ at Hot 97, New York City’s iconic hip-hop station, and a vocal booster of what he calls “real” hip-hop. But as a Jewish fellow from suburban Maryland, he's also the first to admit that he's an unlikely arbiter for what is and what isn't hip-hop. With the help of Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest and NPR's Frannie Kelley, we explore the strange ways that hip-hop deals with that age-old question: are you in or are you out?"]

"The Surprising History of Gun Control, School Shooting Myths, and More ." On the Media (December 21, 2012)

Tofts, Darren. "In My Time of Dying: The Premature Death of a Film Classic." LOLA #1 (2011)

Tracy, Andrew. "Genuine Class: All the Real Girls and All the Right Moves." Reverse Shot #29 (2011)

Vizcarrondo, Sara. "The Art of 'Killing': How Much Truth Comes from the Lie that Tells the Truth?" Documentary (Summer 2013)

Andrew C. Billings: Biographical Omissions -- The Case of A Beautiful Mind and the Search For Authenticity

Biographical Omissions: The Case of A Beautiful Mind and the Search For Authenticity

By Andrew C. Billings

The Film Journal

On March 24, 2002, the Academy Awards concluded with a Best Picture statuette awarded to Ron Howard's A Beautiful Mind, a biopic of the schizophrenic mathematician John Forbes Nash. While Nash's real-life story is remarkable, another story of "overcoming the odds" has been built: the story of how A Beautiful Mind survived a whirlwind of negative publicity to gain the Best Picture award. The controversy stemmed from perceptions that Nash's life has been whitewashed for the silver screen, including the omission of (a) Nash's alleged anti-Semitism, (b) his homosexual leanings, and (c) his divorce and ultimate remarriage to current-wife Alicia Nash (Bunbury, 2002; Lyman, 2002; Mcginty, 2002). Detractors argued that A Beautiful Mind was being irresponsible to omit such large issues, yet Universal Pictures stood behind the film, arguing that no one's life can be portrayed in its entirety and that A Beautiful Mind had been as accurate as possible. The studio went on to say that there was clear evidence of an "orchestrated campaign" against the film that had more to do with winning an Oscar than achieving authenticity (Seiler, 2002, p. 4D). Film historian Pete Hammond argued that this was one of the nastiest campaigns in recent memory, stating that "to accuse the subject of a film of being Anti-Semitic when you know that a lot of the people who will be voting on the Oscars are Jewish, well, that's really down and dirty" (Lyman, 2002, p. 1A).

Within the entire battle over A Beautiful Mind, one can extract a larger question prevalent within the debate concerning the responsibility of a film to portray a historical person or event in an accurate way. How far must a director go to ensure authenticity? In the case of Howard's film, the questions became quite complex. Take, for instance, Nash's homosexual leanings. Giltz (2002b) writes that Nash was frequently referred to as a "homo" in college and also was arrested for public indecency in a men's restroom, ultimately losing his job at the Rand think tank because of the arrest. In fact, the book in which screenwriter Akiva Goldman adapted the movie contained over thirty references to homosexuality, yet all thirty instances were omitted for the movie (Giltz, 2002a). Thus, while no one was arguing that A Beautiful Mind was telling outright lies, they did argue the film was guilty by omission. Contrast this with the equally ugly controversy surrounding the 1996 film Ghosts of Mississippi, chronicling the murder of civil rights leader Medgar Evers and the subsequent trial to exact justice thirty years later. Critics all agreed that Ghosts of Mississippi was "85 to 90 percent true", but, as Medgar Evers' brother Charles states, "the bigger problem is that other 'true' facts are shunted to the background" (Wiltz, 1997). In the case of A Beautiful Mind, some were even arguing that the film was 100% true, but that the majority of the whole truth was left out. In the case of Nash's homosexuality, it was not even an overt choice, as Brian Grazer and Ron Howard were forced to sign a contract that guaranteed the omission of such leanings. Thus, A Beautiful Mind becomes not a case of a director making choices of what to keep and what to leave on the cutting room floor; instead, A Beautiful Mind can be equated with the television journalist who agrees to requests to keep certain topics "off-limits" before interviewing a major public figure.

Hardt (1993) states that the "question of authenticity remains one of the major issues underlying the critique of contemporary social thought" (p. 49). Yet, one must wonder: could anyone, even Nash himself or his wife Alicia, tell a story that is 100 percent true? More succinctly, is authenticity attainable? The latter question must be answered in the negative, as authenticity is an ideal that is unreachable and that American society should implement a new standard for measuring the "accuracy" of historical film narratives. A Beautiful Mind is just the most recent in a long line of films criticized for not being "accurate enough." The debate has been waged for decades.

It is a common notion within academia that nothing we ever say is truly authentic; everything is borrowed directly or indirectly from someone else. In essence, every story we tell is someone else's depiction or at least someone else's language that has been instilled within us through maturation. For instance, if a person were to tell the story of how their first day of school was, it would be their own story, yet their language would be influenced by their background and through other students' perceptions. Clearly, it is likely that a thousand people could each live the exact same day and still render a thousand different authentic stories. Thus, the moral contact with self that Trilling (1969) describes does not really make a story authentic, but it can make a story true. For instance, people who were present at the assassination of John F. Kennedy would all have a true story to tell that would depict their version of the true happenings. Still, as evidenced in the past 30 years, there were many different sides to the same "Truth", making absolute authenticity impossible, even for eyewitnesses of the assassination.

As a result, Visker (1995) argues that the "subject" of any story should be dropped from any argument pertaining to authenticity; the only important aspect of the story is the author/storyteller's ability to recall or retell the story to the best of his or her collective memory. So, in response to the question proposed in the introduction, Visker would argue that who tells the story in Schindler's List is not important; what is of vital importance is that the person telling the story has the ability to tell the story as closely as possible to collective memory found from witnesses and research. In the case of Spielberg's Holocaust epic, this proved to have obstacles of its own, as critics subsequently learned that key scenes, such as Liam Neeson's great "one more person" monologue, were inserted for dramatic effect rather than for historic accuracy.

Yet, beyond the question of the "right to tell a story" comes the larger question of the need to tell the story accurately, another historical Holy Grail. As previously argued, there is no way any director or film producer can tell a story that somehow is or becomes a historical event. Three hundred factually accurate films about the JFK assassination could be made; still they would have three hundred different contexts, equating to three hundred different stories.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

By Andrew C. Billings

The Film Journal

On March 24, 2002, the Academy Awards concluded with a Best Picture statuette awarded to Ron Howard's A Beautiful Mind, a biopic of the schizophrenic mathematician John Forbes Nash. While Nash's real-life story is remarkable, another story of "overcoming the odds" has been built: the story of how A Beautiful Mind survived a whirlwind of negative publicity to gain the Best Picture award. The controversy stemmed from perceptions that Nash's life has been whitewashed for the silver screen, including the omission of (a) Nash's alleged anti-Semitism, (b) his homosexual leanings, and (c) his divorce and ultimate remarriage to current-wife Alicia Nash (Bunbury, 2002; Lyman, 2002; Mcginty, 2002). Detractors argued that A Beautiful Mind was being irresponsible to omit such large issues, yet Universal Pictures stood behind the film, arguing that no one's life can be portrayed in its entirety and that A Beautiful Mind had been as accurate as possible. The studio went on to say that there was clear evidence of an "orchestrated campaign" against the film that had more to do with winning an Oscar than achieving authenticity (Seiler, 2002, p. 4D). Film historian Pete Hammond argued that this was one of the nastiest campaigns in recent memory, stating that "to accuse the subject of a film of being Anti-Semitic when you know that a lot of the people who will be voting on the Oscars are Jewish, well, that's really down and dirty" (Lyman, 2002, p. 1A).

Within the entire battle over A Beautiful Mind, one can extract a larger question prevalent within the debate concerning the responsibility of a film to portray a historical person or event in an accurate way. How far must a director go to ensure authenticity? In the case of Howard's film, the questions became quite complex. Take, for instance, Nash's homosexual leanings. Giltz (2002b) writes that Nash was frequently referred to as a "homo" in college and also was arrested for public indecency in a men's restroom, ultimately losing his job at the Rand think tank because of the arrest. In fact, the book in which screenwriter Akiva Goldman adapted the movie contained over thirty references to homosexuality, yet all thirty instances were omitted for the movie (Giltz, 2002a). Thus, while no one was arguing that A Beautiful Mind was telling outright lies, they did argue the film was guilty by omission. Contrast this with the equally ugly controversy surrounding the 1996 film Ghosts of Mississippi, chronicling the murder of civil rights leader Medgar Evers and the subsequent trial to exact justice thirty years later. Critics all agreed that Ghosts of Mississippi was "85 to 90 percent true", but, as Medgar Evers' brother Charles states, "the bigger problem is that other 'true' facts are shunted to the background" (Wiltz, 1997). In the case of A Beautiful Mind, some were even arguing that the film was 100% true, but that the majority of the whole truth was left out. In the case of Nash's homosexuality, it was not even an overt choice, as Brian Grazer and Ron Howard were forced to sign a contract that guaranteed the omission of such leanings. Thus, A Beautiful Mind becomes not a case of a director making choices of what to keep and what to leave on the cutting room floor; instead, A Beautiful Mind can be equated with the television journalist who agrees to requests to keep certain topics "off-limits" before interviewing a major public figure.

Hardt (1993) states that the "question of authenticity remains one of the major issues underlying the critique of contemporary social thought" (p. 49). Yet, one must wonder: could anyone, even Nash himself or his wife Alicia, tell a story that is 100 percent true? More succinctly, is authenticity attainable? The latter question must be answered in the negative, as authenticity is an ideal that is unreachable and that American society should implement a new standard for measuring the "accuracy" of historical film narratives. A Beautiful Mind is just the most recent in a long line of films criticized for not being "accurate enough." The debate has been waged for decades.

It is a common notion within academia that nothing we ever say is truly authentic; everything is borrowed directly or indirectly from someone else. In essence, every story we tell is someone else's depiction or at least someone else's language that has been instilled within us through maturation. For instance, if a person were to tell the story of how their first day of school was, it would be their own story, yet their language would be influenced by their background and through other students' perceptions. Clearly, it is likely that a thousand people could each live the exact same day and still render a thousand different authentic stories. Thus, the moral contact with self that Trilling (1969) describes does not really make a story authentic, but it can make a story true. For instance, people who were present at the assassination of John F. Kennedy would all have a true story to tell that would depict their version of the true happenings. Still, as evidenced in the past 30 years, there were many different sides to the same "Truth", making absolute authenticity impossible, even for eyewitnesses of the assassination.

As a result, Visker (1995) argues that the "subject" of any story should be dropped from any argument pertaining to authenticity; the only important aspect of the story is the author/storyteller's ability to recall or retell the story to the best of his or her collective memory. So, in response to the question proposed in the introduction, Visker would argue that who tells the story in Schindler's List is not important; what is of vital importance is that the person telling the story has the ability to tell the story as closely as possible to collective memory found from witnesses and research. In the case of Spielberg's Holocaust epic, this proved to have obstacles of its own, as critics subsequently learned that key scenes, such as Liam Neeson's great "one more person" monologue, were inserted for dramatic effect rather than for historic accuracy.

Yet, beyond the question of the "right to tell a story" comes the larger question of the need to tell the story accurately, another historical Holy Grail. As previously argued, there is no way any director or film producer can tell a story that somehow is or becomes a historical event. Three hundred factually accurate films about the JFK assassination could be made; still they would have three hundred different contexts, equating to three hundred different stories.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Tuesday, January 17, 2012

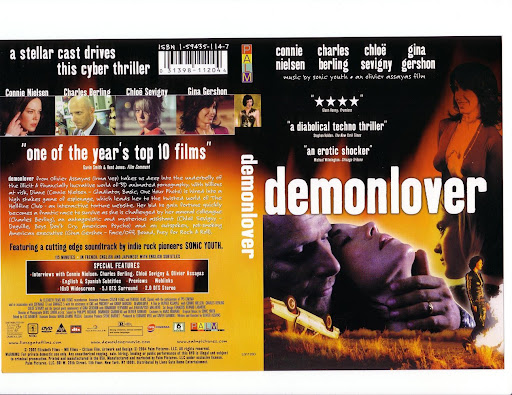

Jason Shawhan: "Qui Est Sylvie Braghier?" -- Identity and Narrative In Olivier Assayas' Demonlover

"Qui Est Sylvie Braghier?": Identity and Narrative In Olivier Assayas' Demonlover

By Jason Shawhan

The Film Journal

"I'm not in charge of anything." -Diane de Monx

Idealized human family relationships, at least in the time of the modern global economy, are a façade. The business world's model is not the proto-nuclear family, but rather that timeless combination of family structure and capitalist motivation: the mafia (1). Underlings enter a closed system, work their way up the ladder by seizing opportunity (and making their own, whether by action or omission of action), and if they manage to stay alive and useful for long enough, they are rewarded with largesse, respect, and the status of an elder. It's just like any established and powerful industry, but the similarities to filmmaking and its star system are particularly fascinating, especially considering some of the thematic ties I feel Olivier Assayas' Demonlover shares with David Lynch's Mulholland Drive (2). If the industry is done with you, where do you go?

There is an unsettling relevance for the casual American viewer of the film. Given the disassociative relationship that many Americans feel with regards to their government (especially over the past two years) and the shifting political environments which time and again cede power to corporate expansion (Halliburton, etc.), what serves as an experimental meditation for some becomes all-too real and ominous for even the most insular of Americans. There is something about Diane de Monx's relationship to her job that speaks to any single person; with neither spouse or children, the world sees you as an expendable source of more tax dollars. "No pain, no gain," we are told, the risk encouraged, the loss devalued.

Much of Demonlover deals with pornography, but not just the glimpses of hentai we see at the TokyoAnime offices or the film that fascinates both Diane and Herve seperately in their respective Tokyo hotel rooms. The world that Volf and Mangatronics inhabit is fetishized with the porn of success: private jets, the freshest fruit, limo rides with stocked bars, the latest breed of cell phones, palm-sized DV cameras, and so very many screens of input (3). It isn't a new thesis that power and money, in extreme doses, lead to extreme habits. Pasolini delivered a fairly definitive statement on the subject with Salo, as did good old Aristide (Joe d'Amato) Massacessi with Emanuelle in America. And Emanuelle in America, so the legend goes, begat Videodrome (4), and from there we dabble in some of David Lynch's pair of psychogenic fugues (Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive), and we have the skeleton around which Assayas' film grows. An intersection between the degradation of the individual by an established industry and a vast conspiracy intertwined with the depiction of sadistic violence.

But it is not only pornography that gives us a key into the world of Demonlover; the influence of video games cannot be understated. This seems most readily apparent after Diane's Tomb Raider-ish infiltration of the hotel room of and catfight to the death with level boss Elaine (5). She kills Elaine, yet is herself taken out, only to awake on that same level with all traces of the battle gone. It is very fortunate for Diane that she had an extra life or two remaining at this point, a feeling which recurs throughout the film as it careens between its spheres of action. This also opens up the disturbing relationship that female icons are subject to in the vast spaces of the internet: Lara Croft, Emma Peel, Wonder Woman, and Storm from The X-Men are all icons of female power degraded at Hell Fire Club for the fantasies and delectations of countless faceless viewers (6).

Assayas' technical skill (along with his dynamic cinematographer Denis Lenoir) is undeniable, never delivering an unengrossing frame, fascinated with patterns of movement and concentric action. Before Elise's dramatic delivery of Karen's message to Diane, there is a stunning moment of the multicolored lights of the Paris streets, diffused through a misty windshield, and it is breathtaking (7). The surfaces which so readily proliferate in the world of the film often create refining subdivisions of the image, accentuating the delicious claustrophobia of the cinemascope frame in the enclosed offices, suites, studios, cars, and torture chambers of the film.

Having read Mark Peranson's interview with Assayas in the Spring 2003 issue of CinemaScope, I am grateful, as it gave me the tools with which to get to the heart of what happens with the story. As an example of the fragmented nature of modern life, it is spot-on, illustrating the way that much of modern thought moves in expansive leaps rather than in linear progression (much like the difference between analog and digital sound), and it is certainly one of the first films to comment on the way that DVD has changed the relationship between film and audience, as anyone with a remote can now unmake aspects of films, dive deeper into them, reshape its context, or just leave it sitting on the shelf in its appropriately fetishized box like the lovely ladies currently featured on Hell Fire Club. Accordingly with Assayas' expressed wishes, Demonlover is eerily relevant to how life is right now. It haunts, thrills, and acquires you; a shiny baubled collection of snapshots from right now, and, miracle of miracles, a film that digs into the soft flesh of the brain and stays there in the hippocampus, where nightmares live and fever dreams flourish.

To Read the Rest of the Review

By Jason Shawhan

The Film Journal

"I'm not in charge of anything." -Diane de Monx

Idealized human family relationships, at least in the time of the modern global economy, are a façade. The business world's model is not the proto-nuclear family, but rather that timeless combination of family structure and capitalist motivation: the mafia (1). Underlings enter a closed system, work their way up the ladder by seizing opportunity (and making their own, whether by action or omission of action), and if they manage to stay alive and useful for long enough, they are rewarded with largesse, respect, and the status of an elder. It's just like any established and powerful industry, but the similarities to filmmaking and its star system are particularly fascinating, especially considering some of the thematic ties I feel Olivier Assayas' Demonlover shares with David Lynch's Mulholland Drive (2). If the industry is done with you, where do you go?

There is an unsettling relevance for the casual American viewer of the film. Given the disassociative relationship that many Americans feel with regards to their government (especially over the past two years) and the shifting political environments which time and again cede power to corporate expansion (Halliburton, etc.), what serves as an experimental meditation for some becomes all-too real and ominous for even the most insular of Americans. There is something about Diane de Monx's relationship to her job that speaks to any single person; with neither spouse or children, the world sees you as an expendable source of more tax dollars. "No pain, no gain," we are told, the risk encouraged, the loss devalued.