By Jason Shawhan

The Film Journal

"I'm not in charge of anything." -Diane de Monx

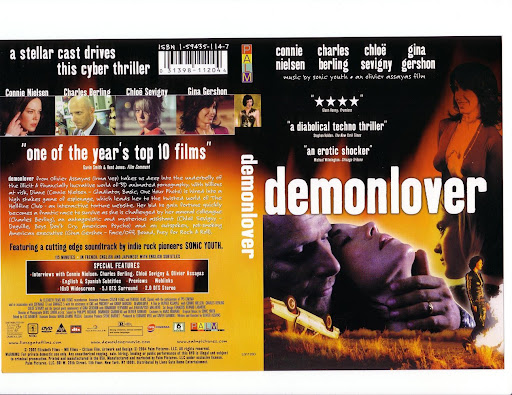

Idealized human family relationships, at least in the time of the modern global economy, are a façade. The business world's model is not the proto-nuclear family, but rather that timeless combination of family structure and capitalist motivation: the mafia (1). Underlings enter a closed system, work their way up the ladder by seizing opportunity (and making their own, whether by action or omission of action), and if they manage to stay alive and useful for long enough, they are rewarded with largesse, respect, and the status of an elder. It's just like any established and powerful industry, but the similarities to filmmaking and its star system are particularly fascinating, especially considering some of the thematic ties I feel Olivier Assayas' Demonlover shares with David Lynch's Mulholland Drive (2). If the industry is done with you, where do you go?

There is an unsettling relevance for the casual American viewer of the film. Given the disassociative relationship that many Americans feel with regards to their government (especially over the past two years) and the shifting political environments which time and again cede power to corporate expansion (Halliburton, etc.), what serves as an experimental meditation for some becomes all-too real and ominous for even the most insular of Americans. There is something about Diane de Monx's relationship to her job that speaks to any single person; with neither spouse or children, the world sees you as an expendable source of more tax dollars. "No pain, no gain," we are told, the risk encouraged, the loss devalued.

Much of Demonlover deals with pornography, but not just the glimpses of hentai we see at the TokyoAnime offices or the film that fascinates both Diane and Herve seperately in their respective Tokyo hotel rooms. The world that Volf and Mangatronics inhabit is fetishized with the porn of success: private jets, the freshest fruit, limo rides with stocked bars, the latest breed of cell phones, palm-sized DV cameras, and so very many screens of input (3). It isn't a new thesis that power and money, in extreme doses, lead to extreme habits. Pasolini delivered a fairly definitive statement on the subject with Salo, as did good old Aristide (Joe d'Amato) Massacessi with Emanuelle in America. And Emanuelle in America, so the legend goes, begat Videodrome (4), and from there we dabble in some of David Lynch's pair of psychogenic fugues (Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive), and we have the skeleton around which Assayas' film grows. An intersection between the degradation of the individual by an established industry and a vast conspiracy intertwined with the depiction of sadistic violence.

But it is not only pornography that gives us a key into the world of Demonlover; the influence of video games cannot be understated. This seems most readily apparent after Diane's Tomb Raider-ish infiltration of the hotel room of and catfight to the death with level boss Elaine (5). She kills Elaine, yet is herself taken out, only to awake on that same level with all traces of the battle gone. It is very fortunate for Diane that she had an extra life or two remaining at this point, a feeling which recurs throughout the film as it careens between its spheres of action. This also opens up the disturbing relationship that female icons are subject to in the vast spaces of the internet: Lara Croft, Emma Peel, Wonder Woman, and Storm from The X-Men are all icons of female power degraded at Hell Fire Club for the fantasies and delectations of countless faceless viewers (6).

Assayas' technical skill (along with his dynamic cinematographer Denis Lenoir) is undeniable, never delivering an unengrossing frame, fascinated with patterns of movement and concentric action. Before Elise's dramatic delivery of Karen's message to Diane, there is a stunning moment of the multicolored lights of the Paris streets, diffused through a misty windshield, and it is breathtaking (7). The surfaces which so readily proliferate in the world of the film often create refining subdivisions of the image, accentuating the delicious claustrophobia of the cinemascope frame in the enclosed offices, suites, studios, cars, and torture chambers of the film.

Having read Mark Peranson's interview with Assayas in the Spring 2003 issue of CinemaScope, I am grateful, as it gave me the tools with which to get to the heart of what happens with the story. As an example of the fragmented nature of modern life, it is spot-on, illustrating the way that much of modern thought moves in expansive leaps rather than in linear progression (much like the difference between analog and digital sound), and it is certainly one of the first films to comment on the way that DVD has changed the relationship between film and audience, as anyone with a remote can now unmake aspects of films, dive deeper into them, reshape its context, or just leave it sitting on the shelf in its appropriately fetishized box like the lovely ladies currently featured on Hell Fire Club. Accordingly with Assayas' expressed wishes, Demonlover is eerily relevant to how life is right now. It haunts, thrills, and acquires you; a shiny baubled collection of snapshots from right now, and, miracle of miracles, a film that digs into the soft flesh of the brain and stays there in the hippocampus, where nightmares live and fever dreams flourish.

To Read the Rest of the Review

No comments:

Post a Comment