Disclaimer: Notes on the death of the American artist

By Guillermo Gómez-Peña

In These Times

People ask me all the time: Is La Pocha Nostra (my performance troupe) being censored in the USA? Tired of silence and diplomacy, with my heart aching and my political consciousness swelling, I now choose to speak.

As a child in Mexico, I heard adults whispering about blacklists and those who named names. My older brother, Carlos, was involved in the 1968 movimiento estudiantil, and several of his friends disappeared for good. During my formative years in Latin America, censorship was indistinguishable from political repression and often resulted in the imprisonment, displacement, exile or death of “dissident” intellectuals and artists.

In the ’70s, many Latin American artists ended up migrating to the United States and Europe, in search of the freedom we couldn’t find in our homelands. When I moved to California in 1978, I found a very different situation. Artists and intellectuals simply didn’t matter. The media treated our art as either an exotic new trend or a human-interest story, and the political class didn’t pay attention to us, which gave us the illusion of freedom. As artists, we rejoiced in our mythical condition of liberty, our celebrated “American freedom.”

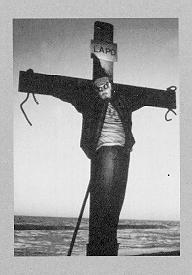

I developed a reputation as an iconoclast by engaging in symbolic acts of transgression that explored and exposed sources of racism and nationalism. Coco Fusco and I exhibited ourselves inside a gilded cage, dressed as fictitious “Indians,” to protest the quincentennial celebrations of Columbus’ arrival in the Western hemisphere (Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit …, 1992–93). Roberto Sifuentes and I crucified ourselves in full mariachi regalia to protest immigration policy (The Cruci-fiction Project, 1994). I became good at organizing ephemeral communities of like-minded rebel artists. I advised activists on how to use performance art strategies to enhance their political actions. I used the art world as a base of operations.

In 20 years of touring the United States as a “radical” performance artist, I have come across innumerable situations in which the content of my “politically direct,” “racially sensitive” and “sexually explicit” material had to be “adapted” and “translated” to the site. Because of this, according to a curator friend of mine, I am “no virgin in the house of censorship.”

Since 9/11, however, my collaborators and I are facing an entirely new dilemma: prohibition—both overtly imposed and internalized. My agent, Nola Mariano, recently told me in a letter:

Besides the ideological censorship exercised by the Bush administration, I believe that we have entered a new era of psychological censorship, one that is sustainable as we, our collaborators, and allies find ourselves second-guessing our audience responses, fearing for our jobs, and unsure of our boards’ support. Unable to quickly identify the opposition, we find ourselves shadowboxing with our conscience and censoring ourselves. This is a victory for a repressive political administration. One not won but rather handed to them.

The imposed culture of panic, prohibition and high security permeating every corner of society—including our arts organizations—has created an incendiary environment for the production of critical culture. We are being offered budgets that are half what we used to work with in the pre-Bush era. As a result, we can only present small-scale projects in the United States, and under technically primitive conditions. These new conditions are similar to those we face in Latin America, but without the community spirit and the humane environment we find there—without people’s willingness to be always present and donate their time and skills.

So far, what has saved La Pocha Nostra from closing our doors is international touring. Sixty percent of our budget now comes from other countries.

As if this weren’t enough, due to “security restrictions,” our props, costumes and art materials are carefully scrutinized at every airport we enter. Homeland Security officers are now even checking the titles of our books and opening our notebooks and phone agendas, both when we leave and when we return to the United States. Frequently our materials are confiscated. Once, our trunk of props was confiscated by security at Boston’s Logan Airport, held for two days, and then delivered to us a half-hour before opening night—with no explanation. Not surprisingly, all the “weird”-looking props were missing, courtesy of Homeland Security. Should we change the nature of our props and art materials, and the way we dress? My colleagues and I are already doing this. Isn’t this a form of censorship?

To Read the Rest of this Essay

More on this subject:

La Pocha Nostra: Performance Art for the New Millennium

The Virtual Barrio and Other Frontiers

-----------------------------------------------

Free Art Agreement

Guillermo Gómez-Peña, 'Free Art Agreement'

In: map. London: Institute of international Visual Arts, 1996, 1-25.

"El Tratado de Libre Cultura" by Guillermo Gómez-Peña,

from The Subversive Imagination

The job of the artist is to force open the matrix of reality to admit unsuspected possibilities. Artists and writers throughout the continent are currently involved in a project of redefinition of our continental topography. We image better maps. We imagine either a map of the Americas without borders, a map turned upside down, or one in which countries having different sizes and borders are organically drawn by geography and culture, not by the capricious fingers of economic domination. Congruent to this continental project, I try to imagine better maps.

I oppose the outdated fragmentation of the map of America with that of Arte-America, a continent made out of people, art and ideas, not countries: when I perform this map becomes my conceptual stage.

I oppose the sinister cartography of the New World Order with that of the New World Border, a great trans- and intercontinental border zone in which no centers remains. It's all margins, meaning there are no "Others" left. Or, better said, the only true "Others" are those resisting fusion, mestizaje, and ongoing dialogue. In this utopian cartography, hybridity becomes the dominant culture; spanglish is the lingua franca, and monoculture becomes a culture of resistance practiced by stubborn Caucasian minorities.

Guillermo Gomez-Pena. Free Art Agreement. 1996

-------------------------------------------------

Multiculturalism and Epistemic Rupture: The Vanishing Acts of Guillermo Gomez-Pena and Alfredo Vea Jr - Critical Essay

From the Tortilla Curtain to the Former East Berlin: The Performances of Guillermo Gomez-Pena and the City In-Between Identities and Times

Radical Changers

Culture-Trafficking for the 21st Century

The New World Border

No comments:

Post a Comment