An examination of Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange

Produced and directed by John Musilli, 1972. [ENG] A discussion with movie critic William Everson, writer Anthony Burgess and actor Malcolm McDowell about Stanley Kubrick's controversial A Clockwork Orange

"My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel--it is, above all, to make you see." -- Joseph Conrad (1897)

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Monday, May 30, 2011

BAFTA: A Life in Pictures - Martin Scorsese

A Life in Pictures: Martin Scorsese

BAFTA

Multi BAFTA-winning filmmaker Martin Scorsese, director of Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and Shutter Island, discusses his upbringing, films and career in this Life in Pictures interview.

Find out how his working class upbringing in New York's Garment District informed his early cinema

Learn about the technical detail that meant Raging Bull's fight scenes took 10 weeks to shoot

Hear about the metaphysics underpinning Shutter Island, and why he feels it's a 'misunderstood' film

To Read the Rest of the Introduction and to Watch the Video

BAFTA

Multi BAFTA-winning filmmaker Martin Scorsese, director of Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and Shutter Island, discusses his upbringing, films and career in this Life in Pictures interview.

Find out how his working class upbringing in New York's Garment District informed his early cinema

Learn about the technical detail that meant Raging Bull's fight scenes took 10 weeks to shoot

Hear about the metaphysics underpinning Shutter Island, and why he feels it's a 'misunderstood' film

To Read the Rest of the Introduction and to Watch the Video

Jason Bellamy and Ed Howard: The Conversations - Terrence Malick, Pt. 1

The Conversations: Terrence Malick, Pt. 1

by Jason Bellamy and Ed Howard

The House Next Door (Slant Magazine)

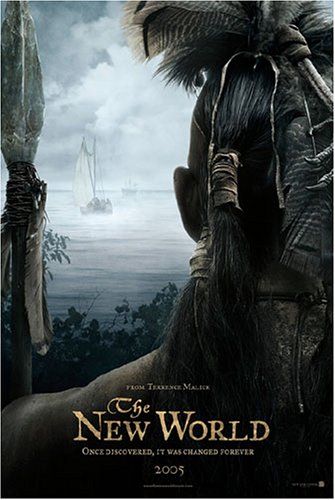

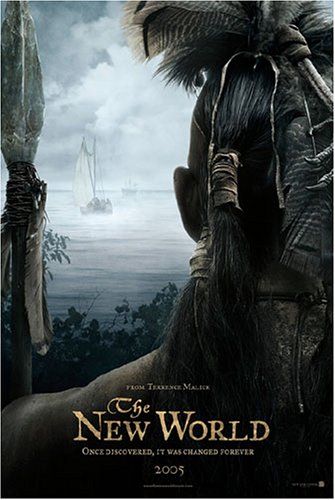

Jason Bellamy: Terrence Malick's next film, due soon in theaters, is called The Tree of Life, and coincidentally or not it is set up by the final shot of Malick's previous film, The New World. In both the theatrical and extended cuts of that 2005 film, Malick closes with a shot at the base of a tree: gazing up the side of its mighty trunk as it stretches heavenward. It's a quintessentially Malickian shot, both in terms of the camera's intimacy to its subject and in the way that it presents nature with a spiritual awe, as if the tree's branches are the flying buttresses of a grand cathedral. But the reason I mention that shot is so I can begin this discussion by acknowledging its roots. We've been regular contributors to The House Next Door for almost two-and-a-half years now, and, as loyal House readers know, Terrence Malick's The New World is the seed from which this blog sprouted. What began in Janurary 2006 as Matt Zoller Seitz's attempt to find enough cyber real estate in which to freely explore his passion for The New World—a rather Malickian quest, if you think about it—became something much bigger, until now here we are: writing about the filmmaker without whom this blog and thus this series might not exist.

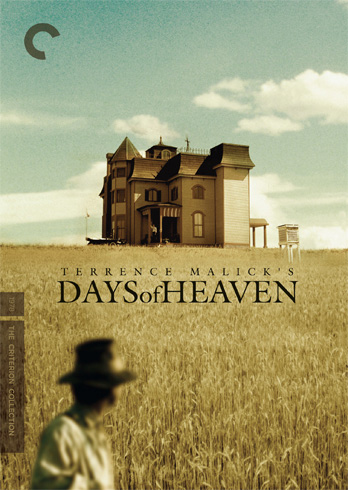

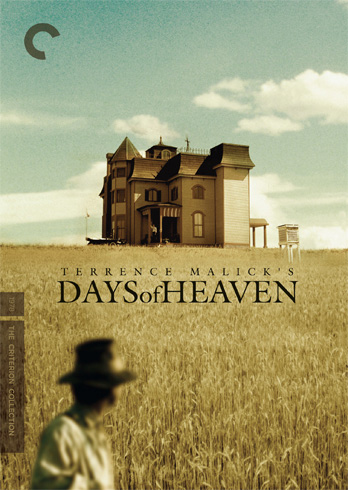

I make that acknowledgement en route to this one: By the very nature of its origins, The House Next Door has always been something of an unofficial Terrence Malick fan club—nay, house of worship. Many of us first gathered at this site because of this subject matter. (Any immediate kinship many of us felt with Matt was inspired by a shared religious experience with The New World, not to mention the holy awakening of seeing serious criticism posted to the Web by amateur means.) I make this observation in the interest of full disclosure—less an acknowledgement of the House's origins, which so many of its readers know already, than an indication of my awareness of it—in the hopes that by doing so I can convince the Malick nonbelievers that they are welcome here. Because, see, Malick is one of those filmmakers who seems to inspire two reactions: genuflecting reverence and head-scratching ennui. Is there room between the two? Or are total immersion and deference to Malick's filmmaking elemental to its effect? In Part I of this discussion, we will look at Malick's first four films, Badlands (1973), Days of Heaven (1978), The Thin Red Line (1998) and The New World (the theatrical cut), and what I hope we begin to uncover is why Malick's filmmaking inspires such divergent reactions.

I am, admittedly, a singer in Malick's choir. His films don't move me equally, but when they do move me I'm profoundly affected. You come into this conversation having just watched most of Malick's films for the first time. So let me ask a question that will cause the Malick agnostics to roll their eyes and the Malick believers to raise their hands to the sky like Pocahontas in The New World: Did Malick's filmmaking inspire you with a unique sense of awe, or do you feel like you're on the outside looking in, or something else?

Ed Howard: You're right, prior to this conversation I had only seen Days of Heaven, so I came to the rest of these films as an agnostic, aware of the two opposing and equally forceful reactions to Malick's work and ready to be either awed or let down. Instead, I find myself thinking that there is room between the two reactions, or rather that there's room to flow between them, to go from being awed one moment to bored the next, to vacillate between thinking that Malick's distinctive sensibility is either sublime or silly.

In that light, I think one major reason that Malick's films are so divisive is that they're so nakedly emotional, that he's so blatantly aiming for the sublime. To be clear, this isn't a criticism. I admire and love all of these films to one degree or another, even though I never quite reach the level of awed transcendence that so many seem to find in Malick's work. I'm saying that Malick aims high, that his films are often not grounded in storytelling or character—instead, his films drift almost irresistibly toward the clouds, toward the treetops, toward the allegorical implications of the basic scenarios he explores. Sometimes that drift sacrifices the human element in his films, so that the characters and their human-scale stories seem to fade into the beautiful landscapes, overlaid with larger allegories about human society and history as a whole.

All of which suggests a grand sense of ambition. Days of Heaven has a very familiar love triangle at its core, but it seldom feels like that story is the point so much as the larger thematic currents about Depression-era America and social hierarchies. The Thin Red Line is packed with individual characters, but the film is really not about any one man as much as it is about their common humanity in the face of mortality and the evils of war. The New World isn't just—or even primarily—a love story but an allegorical fable about the origins of America and a deeply spiritual examination of the dialectic of progress and stasis. The point is, Malick thinks big, juxtaposing the transience and smallness of individual human lives with history-spanning events like the growth of a tree, the slow and unstoppable churning of natural processes. Maybe that's why large, ancient trees are so important to Malick's most recent films: The Thin Red Line begins with a tree, The New World ends with one, and a tree will presumably be at the center of The Tree of Life. A large tree, growing slowly over decades or even centuries, its roots stretching out into the earth even as its branches spread through the sky, is a perfect metaphor for Malick's expansive perspective on life and death, those big-picture subjects that constitute the heart of his work.

JB: That's true. And of course on a very basic level Malick's tree shots evoke not just his themes but his tendencies. Malick's films are famous for—or, in some circles, notorious for—their frequent observations of environment, which in most cases means observations of the natural world. In determining why Malick's films prove divisive, it's safe to start there, because there aren't too many better ways for a director to be written off as pretentiously artsy than to point a camera at flora and fauna and observe them as something beyond mere scenery.

Malick regards nature with fascination and romanticism, replacing the metaphorical textual descriptions of poets with vivid celluloid images. He's unashamed about his reverence, capturing creatures and plant life with the kind of closeups usually reserved for the productions of National Geographic or the Discovery Channel. In Badlands, we are shown branches and leaves, a gasping catfish and a big black beetle. In Days of Heaven, we stare into the husks of the wheat harvest and the tiny jaws of the locusts that devour them. In The Thin Red Line we encounter crocodiles, birds, a snake and a butterfly, all amidst a forbidding jungle. In The New World, it's chickens, cattle, rivers, forests, storms and blue sky. I could go on. Malick presents such images with a deliberateness that makes many viewers uncomfortable, perhaps because nature is the stuff of poetry and poetry is the stuff of emotion and vulnerability. American audiences are accustomed to ogling cars, guns and cityscapes, but not nature. Nature in most American films is the stage on which the action happens. In Malick's films, nature is part of the action itself.

Of course, nature in Malick's films often feels like an observer of the action, too. That's what you were getting at in describing the way Malick juxtaposes "the transience and smallness of individual human lives" with "the slow and unstoppable churning of natural processes." In Malick's films, man chops down nature to make his home. He harvests it to make his fortune. He hides within it to protect his life. He reshapes it to please his own eye. But he never fully conquers it. Nature is too big and too powerful for that, and only nature seems to know it.

To Read the Rest of the Conversation

by Jason Bellamy and Ed Howard

The House Next Door (Slant Magazine)

Jason Bellamy: Terrence Malick's next film, due soon in theaters, is called The Tree of Life, and coincidentally or not it is set up by the final shot of Malick's previous film, The New World. In both the theatrical and extended cuts of that 2005 film, Malick closes with a shot at the base of a tree: gazing up the side of its mighty trunk as it stretches heavenward. It's a quintessentially Malickian shot, both in terms of the camera's intimacy to its subject and in the way that it presents nature with a spiritual awe, as if the tree's branches are the flying buttresses of a grand cathedral. But the reason I mention that shot is so I can begin this discussion by acknowledging its roots. We've been regular contributors to The House Next Door for almost two-and-a-half years now, and, as loyal House readers know, Terrence Malick's The New World is the seed from which this blog sprouted. What began in Janurary 2006 as Matt Zoller Seitz's attempt to find enough cyber real estate in which to freely explore his passion for The New World—a rather Malickian quest, if you think about it—became something much bigger, until now here we are: writing about the filmmaker without whom this blog and thus this series might not exist.

I make that acknowledgement en route to this one: By the very nature of its origins, The House Next Door has always been something of an unofficial Terrence Malick fan club—nay, house of worship. Many of us first gathered at this site because of this subject matter. (Any immediate kinship many of us felt with Matt was inspired by a shared religious experience with The New World, not to mention the holy awakening of seeing serious criticism posted to the Web by amateur means.) I make this observation in the interest of full disclosure—less an acknowledgement of the House's origins, which so many of its readers know already, than an indication of my awareness of it—in the hopes that by doing so I can convince the Malick nonbelievers that they are welcome here. Because, see, Malick is one of those filmmakers who seems to inspire two reactions: genuflecting reverence and head-scratching ennui. Is there room between the two? Or are total immersion and deference to Malick's filmmaking elemental to its effect? In Part I of this discussion, we will look at Malick's first four films, Badlands (1973), Days of Heaven (1978), The Thin Red Line (1998) and The New World (the theatrical cut), and what I hope we begin to uncover is why Malick's filmmaking inspires such divergent reactions.

I am, admittedly, a singer in Malick's choir. His films don't move me equally, but when they do move me I'm profoundly affected. You come into this conversation having just watched most of Malick's films for the first time. So let me ask a question that will cause the Malick agnostics to roll their eyes and the Malick believers to raise their hands to the sky like Pocahontas in The New World: Did Malick's filmmaking inspire you with a unique sense of awe, or do you feel like you're on the outside looking in, or something else?

Ed Howard: You're right, prior to this conversation I had only seen Days of Heaven, so I came to the rest of these films as an agnostic, aware of the two opposing and equally forceful reactions to Malick's work and ready to be either awed or let down. Instead, I find myself thinking that there is room between the two reactions, or rather that there's room to flow between them, to go from being awed one moment to bored the next, to vacillate between thinking that Malick's distinctive sensibility is either sublime or silly.

In that light, I think one major reason that Malick's films are so divisive is that they're so nakedly emotional, that he's so blatantly aiming for the sublime. To be clear, this isn't a criticism. I admire and love all of these films to one degree or another, even though I never quite reach the level of awed transcendence that so many seem to find in Malick's work. I'm saying that Malick aims high, that his films are often not grounded in storytelling or character—instead, his films drift almost irresistibly toward the clouds, toward the treetops, toward the allegorical implications of the basic scenarios he explores. Sometimes that drift sacrifices the human element in his films, so that the characters and their human-scale stories seem to fade into the beautiful landscapes, overlaid with larger allegories about human society and history as a whole.

All of which suggests a grand sense of ambition. Days of Heaven has a very familiar love triangle at its core, but it seldom feels like that story is the point so much as the larger thematic currents about Depression-era America and social hierarchies. The Thin Red Line is packed with individual characters, but the film is really not about any one man as much as it is about their common humanity in the face of mortality and the evils of war. The New World isn't just—or even primarily—a love story but an allegorical fable about the origins of America and a deeply spiritual examination of the dialectic of progress and stasis. The point is, Malick thinks big, juxtaposing the transience and smallness of individual human lives with history-spanning events like the growth of a tree, the slow and unstoppable churning of natural processes. Maybe that's why large, ancient trees are so important to Malick's most recent films: The Thin Red Line begins with a tree, The New World ends with one, and a tree will presumably be at the center of The Tree of Life. A large tree, growing slowly over decades or even centuries, its roots stretching out into the earth even as its branches spread through the sky, is a perfect metaphor for Malick's expansive perspective on life and death, those big-picture subjects that constitute the heart of his work.

JB: That's true. And of course on a very basic level Malick's tree shots evoke not just his themes but his tendencies. Malick's films are famous for—or, in some circles, notorious for—their frequent observations of environment, which in most cases means observations of the natural world. In determining why Malick's films prove divisive, it's safe to start there, because there aren't too many better ways for a director to be written off as pretentiously artsy than to point a camera at flora and fauna and observe them as something beyond mere scenery.

Malick regards nature with fascination and romanticism, replacing the metaphorical textual descriptions of poets with vivid celluloid images. He's unashamed about his reverence, capturing creatures and plant life with the kind of closeups usually reserved for the productions of National Geographic or the Discovery Channel. In Badlands, we are shown branches and leaves, a gasping catfish and a big black beetle. In Days of Heaven, we stare into the husks of the wheat harvest and the tiny jaws of the locusts that devour them. In The Thin Red Line we encounter crocodiles, birds, a snake and a butterfly, all amidst a forbidding jungle. In The New World, it's chickens, cattle, rivers, forests, storms and blue sky. I could go on. Malick presents such images with a deliberateness that makes many viewers uncomfortable, perhaps because nature is the stuff of poetry and poetry is the stuff of emotion and vulnerability. American audiences are accustomed to ogling cars, guns and cityscapes, but not nature. Nature in most American films is the stage on which the action happens. In Malick's films, nature is part of the action itself.

Of course, nature in Malick's films often feels like an observer of the action, too. That's what you were getting at in describing the way Malick juxtaposes "the transience and smallness of individual human lives" with "the slow and unstoppable churning of natural processes." In Malick's films, man chops down nature to make his home. He harvests it to make his fortune. He hides within it to protect his life. He reshapes it to please his own eye. But he never fully conquers it. Nature is too big and too powerful for that, and only nature seems to know it.

To Read the Rest of the Conversation

Sunday, May 29, 2011

12th & Delaware Offers Unique Inside Look at Struggle Between Abortion Clinic and Anti-Abortion Pregnancy Care Center

"12th & Delaware" Offers Unique Inside Look at Struggle Between Abortion Clinic and Anti-Abortion Pregnancy Care Center

Democracy Now

A new documentary by the Oscar-nominated directors of Jesus Camp offers a rare inside look at the pitched battle over abortion rights that’s being waged not just in Congress and the courts, but on the street corners of small-town America—in particular, one street corner where an abortion clinic and an anti-abortion pregnancy care center sit across the street from each other.

Guests:

Rachel Grady, filmmaker, 12th and Delaware

Heidi Ewing, filmmaker, 12th and Delaware

To Watch/Listen/Read

Democracy Now

A new documentary by the Oscar-nominated directors of Jesus Camp offers a rare inside look at the pitched battle over abortion rights that’s being waged not just in Congress and the courts, but on the street corners of small-town America—in particular, one street corner where an abortion clinic and an anti-abortion pregnancy care center sit across the street from each other.

Guests:

Rachel Grady, filmmaker, 12th and Delaware

Heidi Ewing, filmmaker, 12th and Delaware

To Watch/Listen/Read

Hard Core History: #25 The Dyer Outlook

Show 25 - The Dyer Outlook

Dan Carlin's Hardcore History

Dan discusses the past, present and future with influential Canadian historian, broadcaster and columnist Gwynne Dyer.

Notes:

1.“War: The Lethal Custom” by Gwynne Dyer

2.”Future: Tense: The Coming World Order “ by Gwynne Dyer

3.”The Mess They Made: The Middle East After Iraq” by Gwynne Dyer

4.“Climate Wars” by Gwynne Dyer

5.“Ignorant Armies: Sliding into war in Iraq” by Gwynne Dyer

6.“The Defense of Canada” by Gwynne Dyer and Tina Viljoen Dyer

7.“Guns, Germs and Steel” by Jared Diamond

8.“The Guns of August” by Barbara Tuchman

9.“Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire” by Niall Ferguson

10. Gwynne Dyer's website

(From his website) GWYNNE DYER has worked as a freelance journalist, columnist, broadcaster and lecturer on international affairs for more than 20 years, but he was originally trained as an historian. Born in Newfoundland, he received degrees from Canadian, American and British universities, finishing with a Ph.D. in Military and Middle Eastern History from the University of London. He served in three navies and held academic appointments at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and Oxford University before launching his twice-weekly column on international affairs, which is published by over 175 papers in some 45 countries.

His first television series, the 7-part documentary 'War', was aired in 45 countries in the mid-80s. One episode, 'The Profession of Arms', was nominated for an Academy Award. His more recent television work includes the 1994 series 'The Human Race', and 'Protection Force', a three-part series on peacekeepers in Bosnia, both of which won Gemini awards. His award-winning radio documentaries include 'The Gorbachev Revolution', a seven-part series based on Dyer's experiences in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in 1987-90, and 'Millenium', a six-hour series on the

emerging global culture.

Dyer's major study "War", first published in the 1980s, was completely revised and re-published in 2004. During this decade he has also written a trio of more contemporary books dealing with the politics and strategy of the post-9/11 world: 'Ignorant Armies' (2003), 'Future: Tense' (2004), and 'The Mess They Made' (2006). The latter was also published as 'After Iraq' in the US and the UK and as 'Nach Iraq und Afghanistan' in Germany.

His most recent projects are a book and a radio series called 'Climate Wars', dealing with the geopolitics of climate change. They have already been published and aired in some places, and will appear in most other major markets in the course of 2009.

To Listen to the Conversation

Dan Carlin's Hardcore History

Dan discusses the past, present and future with influential Canadian historian, broadcaster and columnist Gwynne Dyer.

Notes:

1.“War: The Lethal Custom” by Gwynne Dyer

2.”Future: Tense: The Coming World Order “ by Gwynne Dyer

3.”The Mess They Made: The Middle East After Iraq” by Gwynne Dyer

4.“Climate Wars” by Gwynne Dyer

5.“Ignorant Armies: Sliding into war in Iraq” by Gwynne Dyer

6.“The Defense of Canada” by Gwynne Dyer and Tina Viljoen Dyer

7.“Guns, Germs and Steel” by Jared Diamond

8.“The Guns of August” by Barbara Tuchman

9.“Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire” by Niall Ferguson

10. Gwynne Dyer's website

(From his website) GWYNNE DYER has worked as a freelance journalist, columnist, broadcaster and lecturer on international affairs for more than 20 years, but he was originally trained as an historian. Born in Newfoundland, he received degrees from Canadian, American and British universities, finishing with a Ph.D. in Military and Middle Eastern History from the University of London. He served in three navies and held academic appointments at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and Oxford University before launching his twice-weekly column on international affairs, which is published by over 175 papers in some 45 countries.

His first television series, the 7-part documentary 'War', was aired in 45 countries in the mid-80s. One episode, 'The Profession of Arms', was nominated for an Academy Award. His more recent television work includes the 1994 series 'The Human Race', and 'Protection Force', a three-part series on peacekeepers in Bosnia, both of which won Gemini awards. His award-winning radio documentaries include 'The Gorbachev Revolution', a seven-part series based on Dyer's experiences in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in 1987-90, and 'Millenium', a six-hour series on the

emerging global culture.

Dyer's major study "War", first published in the 1980s, was completely revised and re-published in 2004. During this decade he has also written a trio of more contemporary books dealing with the politics and strategy of the post-9/11 world: 'Ignorant Armies' (2003), 'Future: Tense' (2004), and 'The Mess They Made' (2006). The latter was also published as 'After Iraq' in the US and the UK and as 'Nach Iraq und Afghanistan' in Germany.

His most recent projects are a book and a radio series called 'Climate Wars', dealing with the geopolitics of climate change. They have already been published and aired in some places, and will appear in most other major markets in the course of 2009.

To Listen to the Conversation

Colin Moynihan and Scott Shane: For Anarchist, Details of Life as F.B.I. Target

For Anarchist, Details of Life as F.B.I. Target

By COLIN MOYNIHAN and SCOTT SHANE

The New York Times

AUSTIN, Tex. — A fat sheaf of F.B.I. reports meticulously details the surveillance that counterterrorism agents directed at the one-story house in East Austin. For at least three years, they traced the license plates of cars parked out front, recorded the comings and goings of residents and guests and, in one case, speculated about a suspicious flat object spread out across the driveway.

“The content could not be determined from the street,” an agent observing from his car reported one day in 2005. “It had a large number of multi-colored blocks, with figures and/or lettering,” the report said, and “may be a sign that is to be used in an upcoming protest.”

Actually, the item in question was more mundane.

“It was a quilt,” said Scott Crow, marveling over the papers at the dining table of his ramshackle home, where he lives with his wife, a housemate and a backyard menagerie that includes two goats, a dozen chickens and a turkey. “For a kids’ after-school program.”

Mr. Crow, 44, a self-described anarchist and veteran organizer of anticorporate demonstrations, is among dozens of political activists across the country known to have come under scrutiny from the F.B.I.’s increased counterterrorism operations since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Other targets of bureau surveillance, which has been criticized by civil liberties groups and mildly faulted by the Justice Department’s inspector general, have included antiwar activists in Pittsburgh, animal rights advocates in Virginia and liberal Roman Catholics in Nebraska. When such investigations produce no criminal charges, their methods rarely come to light publicly.

But Mr. Crow, a lanky Texas native who works at a recycling center, is one of several Austin activists who asked the F.B.I. for their files, citing the Freedom of Information Act. The 440 heavily-redacted pages he received, many bearing the rubric “Domestic Terrorism,” provide a revealing window on the efforts of the bureau, backed by other federal, state and local police agencies, to keep an eye on people it deems dangerous.

In the case of Mr. Crow, who has been arrested a dozen times during demonstrations but has never been convicted of anything more serious than trespassing, the bureau wielded an impressive array of tools, the documents show.

The agents watched from their cars for hours at a time — Mr. Crow recalls one regular as “a fat guy in an S.U.V. with the engine running and the air-conditioning on” — and watched gatherings at a bookstore and cafe. For round-the-clock coverage, they attached a video camera to the phone pole across from his house on New York Avenue.

They tracked Mr. Crow’s phone calls and e-mails and combed through his trash, identifying his bank and mortgage companies, which appear to have been served with subpoenas. They visited gun stores where he shopped for a rifle, noting dryly in one document that a vegan animal rights advocate like Mr. Crow made an unlikely hunter. (He says the weapon was for self-defense in a marginal neighborhood.)

They asked the Internal Revenue Service to examine his tax returns, but backed off after an I.R.S. employee suggested that Mr. Crow’s modest earnings would not impress a jury even if his returns were flawed. (He earns $32,000 a year at Ecology Action of Texas, he said.)

They infiltrated political meetings with undercover police officers and informers. Mr. Crow counts five supposed fellow activists who were reporting to the F.B.I.

Mr. Crow seems alternately astonished, angered and flattered by the government’s attention. “I’ve had times of intense paranoia,” he said, especially when he discovered that some trusted allies were actually spies.

“But first, it makes me laugh,” he said. “It’s just a big farce that the government’s created such paper tigers. Al Qaeda and real terrorists are hard to find. We’re easy to find. It’s outrageous that they would spend so much money surveilling civil activists, and anarchists in particular, and equating our actions with Al Qaeda.”

The investigation of political activists is an old story for the F.B.I., most infamously in the Cointel program, which scrutinized and sometimes harassed civil rights and antiwar advocates from the 1950s to the 1970s. Such activities were reined in after they were exposed by the Senate’s Church Committee, and F.B.I. surveillance has been governed by an evolving set of guidelines set by attorneys general since 1976.

But the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 demonstrated the lethal danger of domestic terrorism, and after the Sept. 11 attacks, the F.B.I. vowed never again to overlook terrorists hiding in plain sight. The Qaeda sleeper cells many Americans feared, though, turned out to be rare or nonexistent.

The result, said Michael German, a former F.B.I. agent now at the American Civil Liberties Union, has been a zeal to investigate political activists who pose no realistic threat of terrorism.

“You have a bunch of guys and women all over the country sent out to find terrorism. Fortunately, there isn’t a lot of terrorism in many communities,” Mr. German said. “So they end up pursuing people who are critical of the government.”

Complaints from the A.C.L.U. prompted the Justice Department’s inspector general to assess the F.B.I.’s forays into domestic surveillance. The resulting report last September absolved the bureau of investigating dissenters based purely on their expression of political views. But the inspector general also found skimpy justification for some investigations, uncertainty about whether any federal crime was even plausible in others and a mislabeling of nonviolent civil disobedience as “terrorism.”

To Read the Rest of the Article

By COLIN MOYNIHAN and SCOTT SHANE

The New York Times

AUSTIN, Tex. — A fat sheaf of F.B.I. reports meticulously details the surveillance that counterterrorism agents directed at the one-story house in East Austin. For at least three years, they traced the license plates of cars parked out front, recorded the comings and goings of residents and guests and, in one case, speculated about a suspicious flat object spread out across the driveway.

“The content could not be determined from the street,” an agent observing from his car reported one day in 2005. “It had a large number of multi-colored blocks, with figures and/or lettering,” the report said, and “may be a sign that is to be used in an upcoming protest.”

Actually, the item in question was more mundane.

“It was a quilt,” said Scott Crow, marveling over the papers at the dining table of his ramshackle home, where he lives with his wife, a housemate and a backyard menagerie that includes two goats, a dozen chickens and a turkey. “For a kids’ after-school program.”

Mr. Crow, 44, a self-described anarchist and veteran organizer of anticorporate demonstrations, is among dozens of political activists across the country known to have come under scrutiny from the F.B.I.’s increased counterterrorism operations since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Other targets of bureau surveillance, which has been criticized by civil liberties groups and mildly faulted by the Justice Department’s inspector general, have included antiwar activists in Pittsburgh, animal rights advocates in Virginia and liberal Roman Catholics in Nebraska. When such investigations produce no criminal charges, their methods rarely come to light publicly.

But Mr. Crow, a lanky Texas native who works at a recycling center, is one of several Austin activists who asked the F.B.I. for their files, citing the Freedom of Information Act. The 440 heavily-redacted pages he received, many bearing the rubric “Domestic Terrorism,” provide a revealing window on the efforts of the bureau, backed by other federal, state and local police agencies, to keep an eye on people it deems dangerous.

In the case of Mr. Crow, who has been arrested a dozen times during demonstrations but has never been convicted of anything more serious than trespassing, the bureau wielded an impressive array of tools, the documents show.

The agents watched from their cars for hours at a time — Mr. Crow recalls one regular as “a fat guy in an S.U.V. with the engine running and the air-conditioning on” — and watched gatherings at a bookstore and cafe. For round-the-clock coverage, they attached a video camera to the phone pole across from his house on New York Avenue.

They tracked Mr. Crow’s phone calls and e-mails and combed through his trash, identifying his bank and mortgage companies, which appear to have been served with subpoenas. They visited gun stores where he shopped for a rifle, noting dryly in one document that a vegan animal rights advocate like Mr. Crow made an unlikely hunter. (He says the weapon was for self-defense in a marginal neighborhood.)

They asked the Internal Revenue Service to examine his tax returns, but backed off after an I.R.S. employee suggested that Mr. Crow’s modest earnings would not impress a jury even if his returns were flawed. (He earns $32,000 a year at Ecology Action of Texas, he said.)

They infiltrated political meetings with undercover police officers and informers. Mr. Crow counts five supposed fellow activists who were reporting to the F.B.I.

Mr. Crow seems alternately astonished, angered and flattered by the government’s attention. “I’ve had times of intense paranoia,” he said, especially when he discovered that some trusted allies were actually spies.

“But first, it makes me laugh,” he said. “It’s just a big farce that the government’s created such paper tigers. Al Qaeda and real terrorists are hard to find. We’re easy to find. It’s outrageous that they would spend so much money surveilling civil activists, and anarchists in particular, and equating our actions with Al Qaeda.”

The investigation of political activists is an old story for the F.B.I., most infamously in the Cointel program, which scrutinized and sometimes harassed civil rights and antiwar advocates from the 1950s to the 1970s. Such activities were reined in after they were exposed by the Senate’s Church Committee, and F.B.I. surveillance has been governed by an evolving set of guidelines set by attorneys general since 1976.

But the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 demonstrated the lethal danger of domestic terrorism, and after the Sept. 11 attacks, the F.B.I. vowed never again to overlook terrorists hiding in plain sight. The Qaeda sleeper cells many Americans feared, though, turned out to be rare or nonexistent.

The result, said Michael German, a former F.B.I. agent now at the American Civil Liberties Union, has been a zeal to investigate political activists who pose no realistic threat of terrorism.

“You have a bunch of guys and women all over the country sent out to find terrorism. Fortunately, there isn’t a lot of terrorism in many communities,” Mr. German said. “So they end up pursuing people who are critical of the government.”

Complaints from the A.C.L.U. prompted the Justice Department’s inspector general to assess the F.B.I.’s forays into domestic surveillance. The resulting report last September absolved the bureau of investigating dissenters based purely on their expression of political views. But the inspector general also found skimpy justification for some investigations, uncertainty about whether any federal crime was even plausible in others and a mislabeling of nonviolent civil disobedience as “terrorism.”

To Read the Rest of the Article

Jonathan Frazen: Liking Is for Cowards. Go for What Hurts.

Liking Is for Cowards. Go for What Hurts.

By JONATHAN FRANZEN

The New York Times

A COUPLE of weeks ago, I replaced my three-year-old BlackBerry Pearl with a much more powerful BlackBerry Bold. Needless to say, I was impressed with how far the technology had advanced in three years. Even when I didn’t have anybody to call or text or e-mail, I wanted to keep fondling my new Bold and experiencing the marvelous clarity of its screen, the silky action of its track pad, the shocking speed of its responses, the beguiling elegance of its graphics.

I was, in short, infatuated with my new device. I’d been similarly infatuated with my old device, of course; but over the years the bloom had faded from our relationship. I’d developed trust issues with my Pearl, accountability issues, compatibility issues and even, toward the end, some doubts about my Pearl’s very sanity, until I’d finally had to admit to myself that I’d outgrown the relationship.

Do I need to point out that — absent some wild, anthropomorphizing projection in which my old BlackBerry felt sad about the waning of my love for it — our relationship was entirely one-sided? Let me point it out anyway.

Let me further point out how ubiquitously the word “sexy” is used to describe late-model gadgets; and how the extremely cool things that we can do now with these gadgets — like impelling them to action with voice commands, or doing that spreading-the-fingers iPhone thing that makes images get bigger — would have looked, to people a hundred years ago, like a magician’s incantations, a magician’s hand gestures; and how, when we want to describe an erotic relationship that’s working perfectly, we speak, indeed, of magic.

Let me toss out the idea that, as our markets discover and respond to what consumers most want, our technology has become extremely adept at creating products that correspond to our fantasy ideal of an erotic relationship, in which the beloved object asks for nothing and gives everything, instantly, and makes us feel all powerful, and doesn’t throw terrible scenes when it’s replaced by an even sexier object and is consigned to a drawer.

To speak more generally, the ultimate goal of technology, the telos of techne, is to replace a natural world that’s indifferent to our wishes — a world of hurricanes and hardships and breakable hearts, a world of resistance — with a world so responsive to our wishes as to be, effectively, a mere extension of the self.

Let me suggest, finally, that the world of techno-consumerism is therefore troubled by real love, and that it has no choice but to trouble love in turn.

Its first line of defense is to commodify its enemy. You can all supply your own favorite, most nauseating examples of the commodification of love. Mine include the wedding industry, TV ads that feature cute young children or the giving of automobiles as Christmas presents, and the particularly grotesque equation of diamond jewelry with everlasting devotion. The message, in each case, is that if you love somebody you should buy stuff.

A related phenomenon is the transformation, courtesy of Facebook, of the verb “to like” from a state of mind to an action that you perform with your computer mouse, from a feeling to an assertion of consumer choice. And liking, in general, is commercial culture’s substitute for loving. The striking thing about all consumer products — and none more so than electronic devices and applications — is that they’re designed to be immensely likable. This is, in fact, the definition of a consumer product, in contrast to the product that is simply itself and whose makers aren’t fixated on your liking it. (I’m thinking here of jet engines, laboratory equipment, serious art and literature.)

But if you consider this in human terms, and you imagine a person defined by a desperation to be liked, what do you see? You see a person without integrity, without a center. In more pathological cases, you see a narcissist — a person who can’t tolerate the tarnishing of his or her self-image that not being liked represents, and who therefore either withdraws from human contact or goes to extreme, integrity-sacrificing lengths to be likable.

If you dedicate your existence to being likable, however, and if you adopt whatever cool persona is necessary to make it happen, it suggests that you’ve despaired of being loved for who you really are. And if you succeed in manipulating other people into liking you, it will be hard not to feel, at some level, contempt for those people, because they’ve fallen for your shtick. You may find yourself becoming depressed, or alcoholic, or, if you’re Donald Trump, running for president (and then quitting).

Consumer technology products would never do anything this unattractive, because they aren’t people. They are, however, great allies and enablers of narcissism. Alongside their built-in eagerness to be liked is a built-in eagerness to reflect well on us. Our lives look a lot more interesting when they’re filtered through the sexy Facebook interface. We star in our own movies, we photograph ourselves incessantly, we click the mouse and a machine confirms our sense of mastery.

And, since our technology is really just an extension of ourselves, we don’t have to have contempt for its manipulability in the way we might with actual people. It’s all one big endless loop. We like the mirror and the mirror likes us. To friend a person is merely to include the person in our private hall of flattering mirrors.

I may be overstating the case, a little bit. Very probably, you’re sick to death of hearing social media disrespected by cranky 51-year-olds. My aim here is mainly to set up a contrast between the narcissistic tendencies of technology and the problem of actual love. My friend Alice Sebold likes to talk about “getting down in the pit and loving somebody.” She has in mind the dirt that love inevitably splatters on the mirror of our self-regard.

The simple fact of the matter is that trying to be perfectly likable is incompatible with loving relationships. Sooner or later, for example, you’re going to find yourself in a hideous, screaming fight, and you’ll hear coming out of your mouth things that you yourself don’t like at all, things that shatter your self-image as a fair, kind, cool, attractive, in-control, funny, likable person. Something realer than likability has come out in you, and suddenly you’re having an actual life.

To Read the Rest of the Commencement Address

By JONATHAN FRANZEN

The New York Times

A COUPLE of weeks ago, I replaced my three-year-old BlackBerry Pearl with a much more powerful BlackBerry Bold. Needless to say, I was impressed with how far the technology had advanced in three years. Even when I didn’t have anybody to call or text or e-mail, I wanted to keep fondling my new Bold and experiencing the marvelous clarity of its screen, the silky action of its track pad, the shocking speed of its responses, the beguiling elegance of its graphics.

I was, in short, infatuated with my new device. I’d been similarly infatuated with my old device, of course; but over the years the bloom had faded from our relationship. I’d developed trust issues with my Pearl, accountability issues, compatibility issues and even, toward the end, some doubts about my Pearl’s very sanity, until I’d finally had to admit to myself that I’d outgrown the relationship.

Do I need to point out that — absent some wild, anthropomorphizing projection in which my old BlackBerry felt sad about the waning of my love for it — our relationship was entirely one-sided? Let me point it out anyway.

Let me further point out how ubiquitously the word “sexy” is used to describe late-model gadgets; and how the extremely cool things that we can do now with these gadgets — like impelling them to action with voice commands, or doing that spreading-the-fingers iPhone thing that makes images get bigger — would have looked, to people a hundred years ago, like a magician’s incantations, a magician’s hand gestures; and how, when we want to describe an erotic relationship that’s working perfectly, we speak, indeed, of magic.

Let me toss out the idea that, as our markets discover and respond to what consumers most want, our technology has become extremely adept at creating products that correspond to our fantasy ideal of an erotic relationship, in which the beloved object asks for nothing and gives everything, instantly, and makes us feel all powerful, and doesn’t throw terrible scenes when it’s replaced by an even sexier object and is consigned to a drawer.

To speak more generally, the ultimate goal of technology, the telos of techne, is to replace a natural world that’s indifferent to our wishes — a world of hurricanes and hardships and breakable hearts, a world of resistance — with a world so responsive to our wishes as to be, effectively, a mere extension of the self.

Let me suggest, finally, that the world of techno-consumerism is therefore troubled by real love, and that it has no choice but to trouble love in turn.

Its first line of defense is to commodify its enemy. You can all supply your own favorite, most nauseating examples of the commodification of love. Mine include the wedding industry, TV ads that feature cute young children or the giving of automobiles as Christmas presents, and the particularly grotesque equation of diamond jewelry with everlasting devotion. The message, in each case, is that if you love somebody you should buy stuff.

A related phenomenon is the transformation, courtesy of Facebook, of the verb “to like” from a state of mind to an action that you perform with your computer mouse, from a feeling to an assertion of consumer choice. And liking, in general, is commercial culture’s substitute for loving. The striking thing about all consumer products — and none more so than electronic devices and applications — is that they’re designed to be immensely likable. This is, in fact, the definition of a consumer product, in contrast to the product that is simply itself and whose makers aren’t fixated on your liking it. (I’m thinking here of jet engines, laboratory equipment, serious art and literature.)

But if you consider this in human terms, and you imagine a person defined by a desperation to be liked, what do you see? You see a person without integrity, without a center. In more pathological cases, you see a narcissist — a person who can’t tolerate the tarnishing of his or her self-image that not being liked represents, and who therefore either withdraws from human contact or goes to extreme, integrity-sacrificing lengths to be likable.

If you dedicate your existence to being likable, however, and if you adopt whatever cool persona is necessary to make it happen, it suggests that you’ve despaired of being loved for who you really are. And if you succeed in manipulating other people into liking you, it will be hard not to feel, at some level, contempt for those people, because they’ve fallen for your shtick. You may find yourself becoming depressed, or alcoholic, or, if you’re Donald Trump, running for president (and then quitting).

Consumer technology products would never do anything this unattractive, because they aren’t people. They are, however, great allies and enablers of narcissism. Alongside their built-in eagerness to be liked is a built-in eagerness to reflect well on us. Our lives look a lot more interesting when they’re filtered through the sexy Facebook interface. We star in our own movies, we photograph ourselves incessantly, we click the mouse and a machine confirms our sense of mastery.

And, since our technology is really just an extension of ourselves, we don’t have to have contempt for its manipulability in the way we might with actual people. It’s all one big endless loop. We like the mirror and the mirror likes us. To friend a person is merely to include the person in our private hall of flattering mirrors.

I may be overstating the case, a little bit. Very probably, you’re sick to death of hearing social media disrespected by cranky 51-year-olds. My aim here is mainly to set up a contrast between the narcissistic tendencies of technology and the problem of actual love. My friend Alice Sebold likes to talk about “getting down in the pit and loving somebody.” She has in mind the dirt that love inevitably splatters on the mirror of our self-regard.

The simple fact of the matter is that trying to be perfectly likable is incompatible with loving relationships. Sooner or later, for example, you’re going to find yourself in a hideous, screaming fight, and you’ll hear coming out of your mouth things that you yourself don’t like at all, things that shatter your self-image as a fair, kind, cool, attractive, in-control, funny, likable person. Something realer than likability has come out in you, and suddenly you’re having an actual life.

To Read the Rest of the Commencement Address

Joanna Chiu: SlutWalk -- Does The Media Make the Message?

SlutWalk: Does The Media Make the Message?

by Joanna Chiu

WIMNs Voices

...

Toronto is the media capital of Canada, so it may have been harder for organizers there to control the messaging. Vancouver is a much smaller city, and SlutWalk Vancouver’s media team made sure to speak to every media organization that requested interviews. They even took the time to respond to the hundreds of questions from Facebook users on their Facebook event page.

Following the publication of my introduction to SlutWalk in The Georgia Straight, the SWV organizers were satisfied with much of the nuanced, in-depth coverage in other media outlets, which relayed an accurate accounting of their goals, as in this Vancouver Observer article:

The Observer piece also contextualized the initial protest within a larger culture of institutional bias that hinders violence prevention efforts. The article drew important connections: “the attitude of victim-blaming expressed by the Toronto Police officer wasn’t isolated,” they reported, referencing a Saanich police rep who encouraged women to watch their behavior and drinking, which some saw as “putting the onus on women to avoid being raped, rather than on attackers to stop assaulting women.”

However, not all Vancouver media got it right. 24 Hours, a free commuter daily newspaper, ran a sensational article that opened with the lede:

SlutWalk Vancouver organizers swiftly issued an open letter responding to 24 Hours:

To me, the 24 Hours article sounded positively benign compared to some critiques of SlutWalk swirling around the Internet, such as this blog post by Aura Blogando, which suggested that organizers are white supremacists. While I commend Blogando for looking at SlutWalk with a critical race analysis, she didn’t appear to have based her judgment on attending an actual SlutWalk event. Which makes me wonder: what if the first depiction of SlutWalk she had come across was the Toronto Star’s white women-centered photo gallery?

Margaret Wente, a columnist based in Toronto, who also did not attend any SlutWalk event, wrote derisively in the Globe and Mail that SlutWalk is “what you get when graduate students in feminist studies run out of things to do.” Wente did not interview any of the SlutWalk organizers for her article. Again, I wonder what media sources Wente looked at before she decided to condemn this movement.

I’m not saying that everyone who disagrees with SlutWalk was duped by inaccurate media portrayals of the marches, the protesters, and their goals. More than 60 SlutWalk events have happened or will happen in cities around the world, and each of those events are grassroots efforts unique to each city. I suspect that even the most media-savvy among us would not be able to make an accurate judgment of each and every SlutWalk from consulting media coverage alone.

That is why I encourage anyone who has the opportunity to attend a SlutWalk event to just go. Even if you end up concluding that the event was trivial or exclusionary, your opinion will have greater credibility and impact if you can draw from your own observations.

In my first-hand report on SlutWalk Vancouver for the Georgia Straight, I noted that almost half of the walk participants were men, that the organizers used the word “feminist” with pride, and that the speakers addressed complex issues, such as the intersectionality of oppression and impacts of the word slut with nuance and careful consideration.

But don’t take my young, starry-eyed liberal feminist word for it.

Harsha Walia, a prominent anti-racist and migrant justice activist, arrived at SlutWalk Vancouver on May 15th with many concerns, including about whether SlutWalk excludes low-income women or women of color. Walia attended anyways, and this is what she observed in her piece for rabble.ca:

...

To Read the Entire Commentary

More responses to Slut Walk:

Tamura A. Lomax: SlutWalk - A Black Feminist Comment on Media, Messages and Meaning

by Joanna Chiu

WIMNs Voices

...

Toronto is the media capital of Canada, so it may have been harder for organizers there to control the messaging. Vancouver is a much smaller city, and SlutWalk Vancouver’s media team made sure to speak to every media organization that requested interviews. They even took the time to respond to the hundreds of questions from Facebook users on their Facebook event page.

Following the publication of my introduction to SlutWalk in The Georgia Straight, the SWV organizers were satisfied with much of the nuanced, in-depth coverage in other media outlets, which relayed an accurate accounting of their goals, as in this Vancouver Observer article:

“‘There is a popular misconception that we are asking people to ‘dress like sluts’ which is completely contrary to our mission,’ Raso argues. She notes the point of the walk is to challenge how the label is used. ‘We recognize that ’slut” is most commonly used in our culture to denote a woman who is assumed to be sexually promiscuous because of how she is dressed, or because of her mannerisms, and that as a ’slut’ she is worth less and deserves less protection.”

The Observer piece also contextualized the initial protest within a larger culture of institutional bias that hinders violence prevention efforts. The article drew important connections: “the attitude of victim-blaming expressed by the Toronto Police officer wasn’t isolated,” they reported, referencing a Saanich police rep who encouraged women to watch their behavior and drinking, which some saw as “putting the onus on women to avoid being raped, rather than on attackers to stop assaulting women.”

However, not all Vancouver media got it right. 24 Hours, a free commuter daily newspaper, ran a sensational article that opened with the lede:

“Women around the globe have joined their “Canadian sisters” to dress provocatively in protest of a Toronto cop’s controversial comments.”

SlutWalk Vancouver organizers swiftly issued an open letter responding to 24 Hours:

“We do not appreciate your paper running a sensational and misinformed article….We would like you to consider mitigating the PR disaster your article could create for our event….[SlutWalk] is not some sensational act focused on dressing provocatively.”

To me, the 24 Hours article sounded positively benign compared to some critiques of SlutWalk swirling around the Internet, such as this blog post by Aura Blogando, which suggested that organizers are white supremacists. While I commend Blogando for looking at SlutWalk with a critical race analysis, she didn’t appear to have based her judgment on attending an actual SlutWalk event. Which makes me wonder: what if the first depiction of SlutWalk she had come across was the Toronto Star’s white women-centered photo gallery?

Margaret Wente, a columnist based in Toronto, who also did not attend any SlutWalk event, wrote derisively in the Globe and Mail that SlutWalk is “what you get when graduate students in feminist studies run out of things to do.” Wente did not interview any of the SlutWalk organizers for her article. Again, I wonder what media sources Wente looked at before she decided to condemn this movement.

I’m not saying that everyone who disagrees with SlutWalk was duped by inaccurate media portrayals of the marches, the protesters, and their goals. More than 60 SlutWalk events have happened or will happen in cities around the world, and each of those events are grassroots efforts unique to each city. I suspect that even the most media-savvy among us would not be able to make an accurate judgment of each and every SlutWalk from consulting media coverage alone.

That is why I encourage anyone who has the opportunity to attend a SlutWalk event to just go. Even if you end up concluding that the event was trivial or exclusionary, your opinion will have greater credibility and impact if you can draw from your own observations.

In my first-hand report on SlutWalk Vancouver for the Georgia Straight, I noted that almost half of the walk participants were men, that the organizers used the word “feminist” with pride, and that the speakers addressed complex issues, such as the intersectionality of oppression and impacts of the word slut with nuance and careful consideration.

But don’t take my young, starry-eyed liberal feminist word for it.

Harsha Walia, a prominent anti-racist and migrant justice activist, arrived at SlutWalk Vancouver on May 15th with many concerns, including about whether SlutWalk excludes low-income women or women of color. Walia attended anyways, and this is what she observed in her piece for rabble.ca:

“I expected to see only a handful of women of color, mothers and children, older women. I was surprised at the actual diversity on the streets, not captured by photographers seeking sensationalist images of bras and fish nets. There was no attempt to recruit everyone into one uniform vision of femininity, nor was there an overarching romanticizing of “sluttiness”; sexual autonomy was being self-determined by each participant — as one placard read “Whether scantily dressed or fully dressed, clothing does not equal consent.” Most heartening was the significant number of teenagers, who are perhaps most pressured against affirming consent and are most impacted by self-shame and victim-blaming, and supporting their voices on the street was a critical gesture of solidarity.”

...

To Read the Entire Commentary

More responses to Slut Walk:

Tamura A. Lomax: SlutWalk - A Black Feminist Comment on Media, Messages and Meaning

Committee to Stop FBI Repression Statement: Secret FBI documents reveal attack on democratic rights of anti-war and international solidarity activists

Secret FBI documents reveal attack on democratic rights of anti-war and international solidarity activists

Committee to Stop FBI Repression Statement (May 18, 2011)

Committee to Stop FBI Repression

FBI agents, who raided the home of Mick Kelly and Linden Gawboy, took with them thousands of pages of documents and books, along with computers, cell phones and a passport. By mistake, they also left something behind; the operation plans for the raid, “Interview questions” for anti-war and international solidarity activists, duplicate evidence collection forms, etc. The file of secret FBI documents was accidently mixed in with Gawboy’s files, and was found in a filing cabinet on April 30. We are now releasing them to the public.

To Access the Documents

Committee to Stop FBI Repression Statement (May 18, 2011)

Committee to Stop FBI Repression

FBI agents, who raided the home of Mick Kelly and Linden Gawboy, took with them thousands of pages of documents and books, along with computers, cell phones and a passport. By mistake, they also left something behind; the operation plans for the raid, “Interview questions” for anti-war and international solidarity activists, duplicate evidence collection forms, etc. The file of secret FBI documents was accidently mixed in with Gawboy’s files, and was found in a filing cabinet on April 30. We are now releasing them to the public.

To Access the Documents

Saturday, May 28, 2011

The American Society of Cinematographers: Lance Accord -- Where the Wild Things Are

The American Society of Cinematographers

Where The Wild Things Are: Lance Acord, ASC - Part 1

Lance Acord, ASC, cinematographer of Spike Jonze’ adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, discusses the creative underpinnings of this film and the techniques he used to tackle its artistic challenges with fellow ASC member Rodney Taylor.

Where The Wild Things Are: Lance Acord, ASC - Part 2

Lance Acord, ASC, cinematographer of Where the Wild Things Are, continues his conversation with fellow ASC member Rodney Taylor, focusing on his career and the art scene in Los Angeles and San Francisco in the 80s.

To Listen to the Conversation

Where The Wild Things Are: Lance Acord, ASC - Part 1

Lance Acord, ASC, cinematographer of Spike Jonze’ adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, discusses the creative underpinnings of this film and the techniques he used to tackle its artistic challenges with fellow ASC member Rodney Taylor.

Where The Wild Things Are: Lance Acord, ASC - Part 2

Lance Acord, ASC, cinematographer of Where the Wild Things Are, continues his conversation with fellow ASC member Rodney Taylor, focusing on his career and the art scene in Los Angeles and San Francisco in the 80s.

To Listen to the Conversation

Peter Hames: In the Shadow of the Werewolf - František Vláčil's Markéta Lazarová

In the Shadow of the Werewolf: František Vláčil's Markéta Lazarová

by Peter Hames

Central Europe Review

Dawn breaks against a black and white snowscape and a party of wolves makes its way obliquely towards the camera. A hawk hovers above the marsh reeds and we note that it is linked to the hand of its master. The sombre photography and the images of hunters, both animal and human, establish the context of a harsh and predatory world.

This is the opening to František Vláčil's 13th-century epic Markéta Lazarová . It's a film from the mid-1960s, and by no means a familiar title, yet some rank it as one of the best films ever made. In the Czech Republic, a poll of film professionals has ranked it as the best Czech film. That places it above the work of Miloš Forman, Jan Švankmajer, and Oscar-winning titles such as Ostře sledované vlaky (Closely Observed Trains) and Obchod na korze (A Shop on the High Street).

Adapted from a pre-war novel by the avant-garde writer, Vladislav Vančura, Vláčil's film deals with the conflicts between the rival clans of the Kozlíks and the Lazars, and the doomed love affair between Mikoláš Kozlík and Markéta Lazarová. Interwoven with all this is an evocation of the conflict between Christianity and paganism.

Revealing the essence

Vláčil's objectives run counter to the traditional historical film in which he felt he was "seeing contemporary people dressed up in historical costumes." He sought instead to penetrate the psychology of the times. "People then were much more instinctive in their actions, and hence much more consistent. The controlling emotion was fear, and that brought its pressure to bear mainly at night. That is why some pagan customs stayed with man for such a long time."

Not satisfied with a purely intellectual exercise, he took his cast and film team to the Šumava forest for two years. "There we lived like animals ...lacking food, and dressed in rags. I wanted my actors to live their parts. Finally they did. And they loved me, because I gave them the opportunity to live the way they always wanted."

While he was clearly influenced by models such as Ingmar Bergman's Det Sjunde inseglet (The Seventh Seal, 1957) and Akira Kurosawa's Shichinin no samurai (Seven Samurai, 1954), Vláčil's ambitions reached further. Apart from authentic clothes, implements, and sets constructed by traditional methods, he drew on anthropological studies and used historical language. Like the original novel, he attempted to reveal the essence of human nature.

Despite its extended period of preparation and shooting, the film has the intensity of an almost instantaneous inspiration. The combination of an elliptical narrative with a visually rich and evocative style produces a powerful and fascinating film.

Rich and hallucinogenic

Dramatic scenes such as the attack on a Saxon count and his retinue, a battle filmed as hallucination, and scenes of sexual passion, contrast with rare episodes of repose. The story is complemented by powerful animal images—the raven, the snake, the deer, and the lamb—a poetic menagerie of hunters and hunted. The superstition of the werewolf, common at the time, hangs over the characters' actions.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by Peter Hames

Central Europe Review

Dawn breaks against a black and white snowscape and a party of wolves makes its way obliquely towards the camera. A hawk hovers above the marsh reeds and we note that it is linked to the hand of its master. The sombre photography and the images of hunters, both animal and human, establish the context of a harsh and predatory world.

This is the opening to František Vláčil's 13th-century epic Markéta Lazarová . It's a film from the mid-1960s, and by no means a familiar title, yet some rank it as one of the best films ever made. In the Czech Republic, a poll of film professionals has ranked it as the best Czech film. That places it above the work of Miloš Forman, Jan Švankmajer, and Oscar-winning titles such as Ostře sledované vlaky (Closely Observed Trains) and Obchod na korze (A Shop on the High Street).

Adapted from a pre-war novel by the avant-garde writer, Vladislav Vančura, Vláčil's film deals with the conflicts between the rival clans of the Kozlíks and the Lazars, and the doomed love affair between Mikoláš Kozlík and Markéta Lazarová. Interwoven with all this is an evocation of the conflict between Christianity and paganism.

Revealing the essence

Vláčil's objectives run counter to the traditional historical film in which he felt he was "seeing contemporary people dressed up in historical costumes." He sought instead to penetrate the psychology of the times. "People then were much more instinctive in their actions, and hence much more consistent. The controlling emotion was fear, and that brought its pressure to bear mainly at night. That is why some pagan customs stayed with man for such a long time."

Not satisfied with a purely intellectual exercise, he took his cast and film team to the Šumava forest for two years. "There we lived like animals ...lacking food, and dressed in rags. I wanted my actors to live their parts. Finally they did. And they loved me, because I gave them the opportunity to live the way they always wanted."

While he was clearly influenced by models such as Ingmar Bergman's Det Sjunde inseglet (The Seventh Seal, 1957) and Akira Kurosawa's Shichinin no samurai (Seven Samurai, 1954), Vláčil's ambitions reached further. Apart from authentic clothes, implements, and sets constructed by traditional methods, he drew on anthropological studies and used historical language. Like the original novel, he attempted to reveal the essence of human nature.

Despite its extended period of preparation and shooting, the film has the intensity of an almost instantaneous inspiration. The combination of an elliptical narrative with a visually rich and evocative style produces a powerful and fascinating film.

Rich and hallucinogenic

Dramatic scenes such as the attack on a Saxon count and his retinue, a battle filmed as hallucination, and scenes of sexual passion, contrast with rare episodes of repose. The story is complemented by powerful animal images—the raven, the snake, the deer, and the lamb—a poetic menagerie of hunters and hunted. The superstition of the werewolf, common at the time, hangs over the characters' actions.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

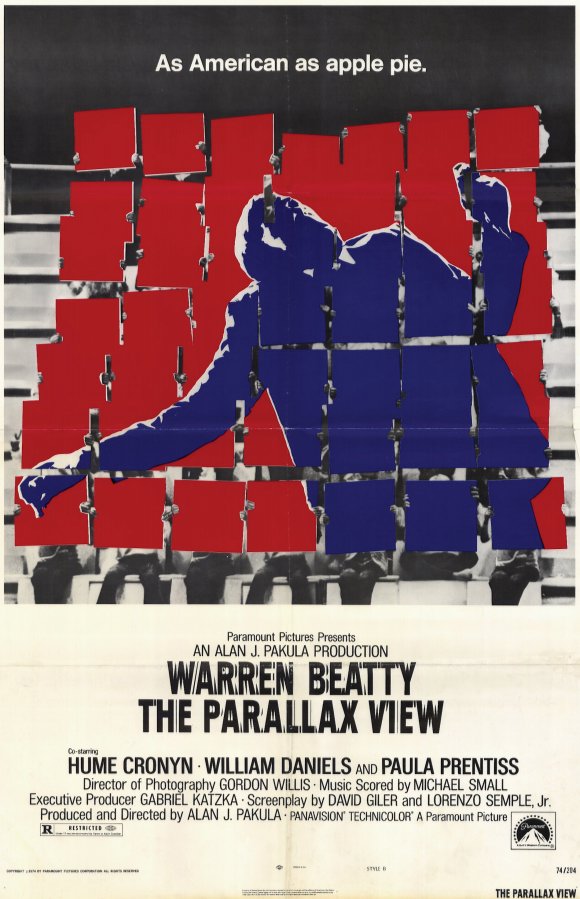

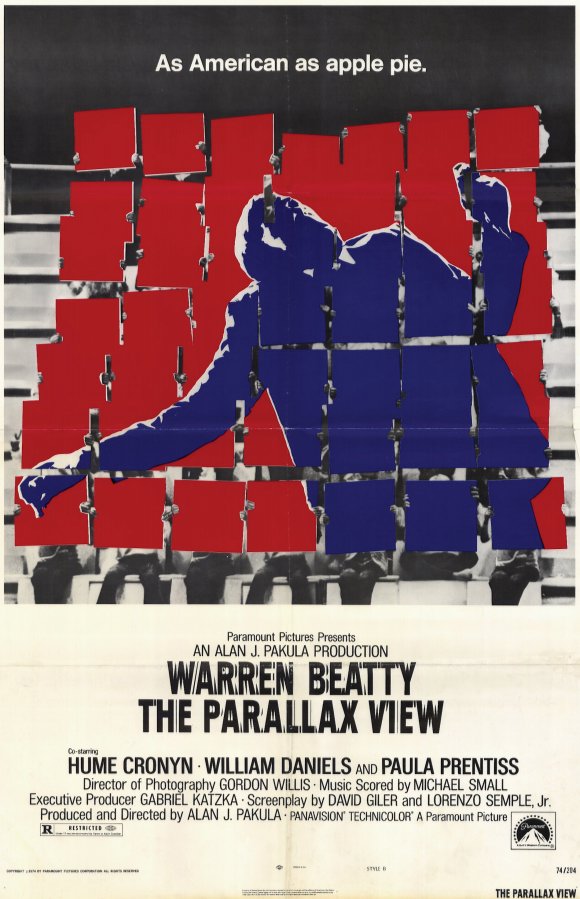

Damon Smith: America is Watching -- Southland Tales and The Parallax View

America Is Watching

Damon Smith on Southland Tales and The Parallax View

Reverse Shot

“The pure products of America/go crazy”—William Carlos Williams

Paranoia has been out of fashion in the movies since the 1970s. After Oliver Stone’s JFK, the last serious Hollywood-style entry of the post-Kennedy era to posit a hinky what-if conspiratorial scenario, Richard Donner’s execrable Conspiracy Theory, featuring a wild-eyed, motor-mouthed Mel Gibson, demonstrated how marginalized and discredited such tortuously convoluted mindsets had become to the mainstream. In the late ’90s, the American empire was flourishing, and world conflict seemed distant. The X-Files movie, created by Paranoiac-in-Chief Chris Carter, was more an homage to TV’s favorite paranormal investigators Mulder and Scully than it was an attempt to version reality; it was character-based rather than event-driven. But the tragedy of 9/11 roiled all the old fears about government deception, and the culture industry set about its work: Jonathan Demme remade The Manchurian Candidate, AMC created the series Rubicon, modeled after the classic paranoid thrillers, and the Truth Movement gained a foothold, thanks to the Internet-distributed documentary Loose Change. This film, a farrago of irresponsible, sensationalized conjecture, stoked the imagination of those primed to believe that the Bush administration had either orchestrated the attacks on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center towers, or had allowed the hijackers to implement mass murder in accordance with a neo-conservative ideology hatched under the aegis of William Kristol and Robert Kagan’s Project for the New American Century. Theories like these proved that the will to believe anything was still a feature of American public discourse and its politically disenfranchised classes.

By late 2007, as critics dutifully compiled their year-end best-of lists, one film in particular seemed to be vying with Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (an allegory of capitalism-as-madness) for the grand prize of over-the-top, deranged masterpiece: Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales, an independently financed, studio-distributed amalgam of Biblical and pop-cultural prophesying spiked with a heady dose of security-state paranoia. Unlike films of the earlier era—Executive Action and Marathon Man, The Conversation and Three Days of the Condor—or present-day thrillers which sought to explain world events in terms of secret political or corporate rationales (Michael Clayton’s tagline: “The truth can be adjusted”), Kelly’s logic-defying Southland Tales was a baffling exercise in futuristic, sci-fi apocalyptica that appears to have burst like a loose, baggy monster from the director’s adolescent id.

The story, like the film itself, is incredibly knotted and nearly impossible to summarize. It doesn’t help that the movie begins with an atomic bomb exploding on the Fourth of July 2008 in Abilene, Texas, and the onset of World War III in the Axis of Evil nations, information conveyed to us by a narrator, Pilot Abilene (Justin Timberlake), who happens to be a badly disfigured Iraq War veteran and drug addict. From there, we enter the world of an amnesiac, Republican Party–connected action-movie star, Boxer Santaros (Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson), who, after vanishing in the Nevada desert for several days, returns believing he is Jericho Kane, a fictional character from a screenplay he’s co-written with celebrity porn star and talk-show host Krysta Now (Sarah Michelle Gellar) about the end of the world. The reasons for his disappearance have to do with the machinations of an evil baron (Wallace Shawn), a troupe of culture-jamming neo-Marxist renegades, the advent of new government program USIdent, and the tortured recollections of L.A. police officer and Fallujah survivor (Seann William Scott). Got all that?

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Damon Smith on Southland Tales and The Parallax View

Reverse Shot

“The pure products of America/go crazy”—William Carlos Williams

Paranoia has been out of fashion in the movies since the 1970s. After Oliver Stone’s JFK, the last serious Hollywood-style entry of the post-Kennedy era to posit a hinky what-if conspiratorial scenario, Richard Donner’s execrable Conspiracy Theory, featuring a wild-eyed, motor-mouthed Mel Gibson, demonstrated how marginalized and discredited such tortuously convoluted mindsets had become to the mainstream. In the late ’90s, the American empire was flourishing, and world conflict seemed distant. The X-Files movie, created by Paranoiac-in-Chief Chris Carter, was more an homage to TV’s favorite paranormal investigators Mulder and Scully than it was an attempt to version reality; it was character-based rather than event-driven. But the tragedy of 9/11 roiled all the old fears about government deception, and the culture industry set about its work: Jonathan Demme remade The Manchurian Candidate, AMC created the series Rubicon, modeled after the classic paranoid thrillers, and the Truth Movement gained a foothold, thanks to the Internet-distributed documentary Loose Change. This film, a farrago of irresponsible, sensationalized conjecture, stoked the imagination of those primed to believe that the Bush administration had either orchestrated the attacks on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center towers, or had allowed the hijackers to implement mass murder in accordance with a neo-conservative ideology hatched under the aegis of William Kristol and Robert Kagan’s Project for the New American Century. Theories like these proved that the will to believe anything was still a feature of American public discourse and its politically disenfranchised classes.

By late 2007, as critics dutifully compiled their year-end best-of lists, one film in particular seemed to be vying with Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (an allegory of capitalism-as-madness) for the grand prize of over-the-top, deranged masterpiece: Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales, an independently financed, studio-distributed amalgam of Biblical and pop-cultural prophesying spiked with a heady dose of security-state paranoia. Unlike films of the earlier era—Executive Action and Marathon Man, The Conversation and Three Days of the Condor—or present-day thrillers which sought to explain world events in terms of secret political or corporate rationales (Michael Clayton’s tagline: “The truth can be adjusted”), Kelly’s logic-defying Southland Tales was a baffling exercise in futuristic, sci-fi apocalyptica that appears to have burst like a loose, baggy monster from the director’s adolescent id.

The story, like the film itself, is incredibly knotted and nearly impossible to summarize. It doesn’t help that the movie begins with an atomic bomb exploding on the Fourth of July 2008 in Abilene, Texas, and the onset of World War III in the Axis of Evil nations, information conveyed to us by a narrator, Pilot Abilene (Justin Timberlake), who happens to be a badly disfigured Iraq War veteran and drug addict. From there, we enter the world of an amnesiac, Republican Party–connected action-movie star, Boxer Santaros (Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson), who, after vanishing in the Nevada desert for several days, returns believing he is Jericho Kane, a fictional character from a screenplay he’s co-written with celebrity porn star and talk-show host Krysta Now (Sarah Michelle Gellar) about the end of the world. The reasons for his disappearance have to do with the machinations of an evil baron (Wallace Shawn), a troupe of culture-jamming neo-Marxist renegades, the advent of new government program USIdent, and the tortured recollections of L.A. police officer and Fallujah survivor (Seann William Scott). Got all that?

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Friday, May 27, 2011

Thursday, May 26, 2011

Common Sense with Dan Carlin: #169 Money Talks

#169 Money Talks

Common Sense with Dan Carlin

A Supreme Court decision involving campaign finance has Dan thinking about ways to level the Free Speech playing field. He also interviews Jackie Salit of independenttvoting.org and the Neo-Independent Magazine.

Notes:

1. U.S. Supreme Court case "United v. Federal Election Commission" Justice Stevens' Dissenting Opinion

2. "Court Ruling Invites a Boom in Political Ads" by Brian Stelter for The New York Times, January 25, 2010.

3. "The Corporate States of America" by E.J. Dionne for The Washington Post, January 24, 2010.

4. "41 industry leaders call on Congress to halt corporate 'bribery' " by The Raw Story, January 26, 2010.

5. "Lobbyist gift limit survives" by the Eugene Register-Guard Editorial Staff, January 5, 2010.

To Listen to the Episode

Common Sense with Dan Carlin

A Supreme Court decision involving campaign finance has Dan thinking about ways to level the Free Speech playing field. He also interviews Jackie Salit of independenttvoting.org and the Neo-Independent Magazine.

Notes:

1. U.S. Supreme Court case "United v. Federal Election Commission" Justice Stevens' Dissenting Opinion

2. "Court Ruling Invites a Boom in Political Ads" by Brian Stelter for The New York Times, January 25, 2010.

3. "The Corporate States of America" by E.J. Dionne for The Washington Post, January 24, 2010.

4. "41 industry leaders call on Congress to halt corporate 'bribery' " by The Raw Story, January 26, 2010.

5. "Lobbyist gift limit survives" by the Eugene Register-Guard Editorial Staff, January 5, 2010.

To Listen to the Episode

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

Conversations with History: Philip Gourevitch - Reporting the Story of a Genocide

Philip Gourevitch - Reporting the Story of a Genocide

Conversations with History (Institute of International Studies at the University of California, Berkeley)

Interviewed by Harry Kreisler