by John R. Hamilton

Senses of Cinema

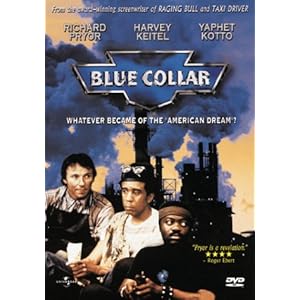

What is this desire Paul Schrader has for writing or directing films about losers or those on the edge of society: Robert de Niro in Taxi Driver (1976), Richard Gere as an American Gigolo (1980), the runaway girl in Hardcore (1979), the suicidal Mishima (1985), the washed-up prize fighter in Raging Bull (1980), the deviant savior in The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), the Stockholm-syndromed kidnapped heiress Patty Hearst (1988), or the burnt-out urban savior in Bringing Out the Dead (1999)? Is it something in his Calvinist upbringing in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where to warn him of the flames of hell, Schrader’s mother passed his little hands over a burning match? Yet at the same time he learned there the promise of salvation and redemption.

From the beginning, Schrader’s characters have shown a profound spiritual hunger. Kevin Jackson’s summary of Schrader’s career voices a typical observation, that already by the mid-1970s, his scripts were all “harsh and anguished, full of metaphors for imprisonment, preoccupied with vengeance and the thirst for redemption.” (1) (This same evaluation might also aptly describe many of the films of Clint Eastwood.)

Paul Schrader is the philosopher’s “movie brat” director. His contemporaries, film school alumni whom Hollywood gave a shot in the late ‘60s and ‘70s to try to bolster their failing box office, include Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Spielberg. Instead of coming up through the ranks of the craft guilds, these young directors studied film history, auteur theory, and audience-pleasing techniques at New York University (NYU), University of Southern California (USC), University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), and Cal State, respectively. After Calvin College, Schrader’s masters thesis at UCLA was on the esoteric style of Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu, Frenchman Robert Bresson, and Swede Carl Theodor Dreyer, whose austere “transcendental style” resonated with Schrader’s Calvinist leanings. The thesis was published in book form by the prestigious University of California Press, (2) when even very few doctoral dissertations see the light of print.

All of the movie brat directors named here became wildly commercial and mainstream, although Coppola’s career somewhat stalled out. Only Schrader can be said to have remained fairly consistently committed to deeper, psychologically darker material. He is an unabashed modernist, believing in existential struggles and reality, never lightening up or embracing a postmodern ethos in order to grab for a pop culture audience. That he has been able to continue to find financing, actors, and distributors with this approach is astonishing and encouraging, albeit not without constant application of the protestant work ethic, and sometimes years of knocking on doors and multiple rejections before finding the right combination to unlock the green-lit path. (For example, it took him four tries to get the right lead actor for The Walker (2007), and that after years in development.)

But Schrader seems to have internalised Jesus’ teaching that one must first “seek the kingdom” and be committed to one’s values and goals, rather than worrying about fame and fortune (Matthew 6:31-34). He says bluntly, “I would rather do something really small of some value than do what Marty Scorsese’s doing. I don’t see the fun in that. “ (3)

Schrader also has continually to compete against himself. Perhaps it is the curse of peaking too early. With the brilliance and success of his first produced screenplay, Taxi Driver, (4) Schrader has had the onus of having to live up to that work ever since. There are many examples of this artistic phenomenon in literature and cinema, such as William Golding’s lifelong burden of his first novel, which he found “boring and crude,” Lord of the Flies. (5)

When he speaks of doing something of value, Schrader often returns to his school days, when he wanted to stand up for the oppressed, defend the outcasts, and challenge the establishment. “There’s always been something adversarial and evangelical about my interest in film.” (6) However, this is not garden variety liberalism. One of the strong strains in reformational Calvinist philosophy is the idea of the radical third way, neither conservative nor liberal, but breaking out into a new paradigm which is informed by Biblical principles. (7)

Thus, Schrader’s early essays in film criticism for the L. A. Free Press stood apart from typical auteur or sociological analysis of the day, but also from the leftism of the underground press. He trashed Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969), for example, as being cliched and indulging in predictable stereotypes of hippies vs. rednecks.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment