J. G. Ballard

By Richard Behrens

The Modern Word

"Fiction is a branch of neurology: the scenarios of nerve and blood vessel are the written mythologies of memory and desire."

-- J.G. Ballard

Introduction

Working quietly over the last forty years from the domestic seclusion of a London suburb, J.G. Ballard has proven to be one of the world's most imaginative and thought-provoking writers. His books are primarily known to readers of science fiction, but he has produced work that crosses many boundaries, borrowing from and blending several genres, fusing action adventure with hard science, psychiatry with surrealism, and postmodernism with pulp narratives. His stories, often hallucinatory or dreamlike in character, are futurist predictions of where technology, media and the internal logic of our own suburban landscapes may be leading us. Ballard has described his mission as writing "a mythology of the future" and that is about as accurate a label as you can give to his collected works.

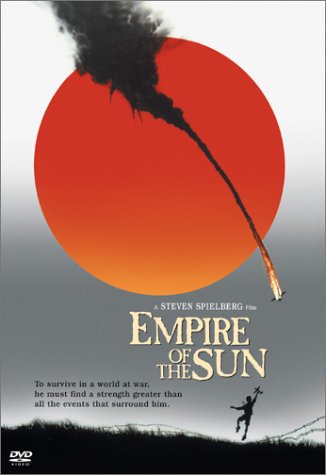

To a mainstream audience, he is the author of Empire of the Sun, a novel about his wartime experiences in China, and Crash, a puzzling and disturbing novel about the sexuality of car crashes. Both have been made into Hollywood movies, the former to great acclaim by Stephen Spielberg in 1985 and the later by David Cronenberg in 1995 amidst a controversy that resulted in the film being banned from certain parts of London. Both films have done justice to the source material, mixing Ballard's authentic poetic sensibilities with the highly individual visions of their respective directors. Hopefully, the films have helped his books find a new generation of readers.

Ballard has never stayed with the perimeters of his chosen professions. As a medical student in Cambridge, he looked at the dissected corpses upon which he labored with the subconscious fascination of a Surrealist poet. In The Kindness of Women, he wrote: "I held her dissected hand, whose nerves and tendons I had teased into the light. Its layers of skin and muscle resembled a deck of cards that she waited to deal across the table to me." As an RAF pilot-in-training, he was more concerned with the dream of mass atomic destruction than the craft of flying: "The mysterious mushroom clouds . . . were a powerful incitement to the psychotic imagination, sanctioning everything."

Likewise, as a science fiction writer, he shied away from the usual trappings of the genre. Missing are the spaceships, galactic empires, and imaginary fantasy worlds with their elven kingdoms and fanciful histories. Also gone are the alien races, the flying saucers and mutated atomic monsters so prevalent in the science fiction of the 1950's when Ballard got his start. Instead we are treated to a poet's vision of a haunted world. Though still essentially grounded in science fiction (his future technologies and ecological disasters are unsurpassed in the genre), reading one of his books is like falling into the interior world of a Surrealist painting.

Ballard often said that the main difference between a Surrealist landscape and one painted by a classical artist is that the Surrealist landscape is lacking the element of time. Whereas the scenes depicted by Rembrandt, for example, are always very explicit about time -- the light of the sun penetrating the picture in such a way that you can always pinpoint the time of day -- a landscape by Ernst shows a place where the element of time has been extracted. Ballard has tried over and again to not only portray these timeless landscapes (often needing to destroy civilization to bring them about in a way that makes narrative sense), but he has shown his main characters suffering from a time extraction that is very real.

Dr. Nathan passed the illustration across his desk to Margaret Travis. "Marey's chronograms are multiple-exposure photographs in which the element of time is visible-the walking human figure, for example represented as a series of dune-like lumps . . . Your husband's brilliant feat was to reverse the process. Using a series of photographs of the most commonplace objects-this office, let us say, a panorama of New York skyscrapers, the naked body of a woman, the face of a catatonic patient-he treated them as if they already were chronograms and extracted the element of time." Dr. Nathan lit his cigarette with care. 'The results were extraordinary. A very different world was revealed. The familiar surroundings of our lives, even our smallest gestures, were seen to have total altered meanings. As for the reclining figure of a film star, or this hospital...." (The Atrocity Exhibition)

The virus in The Crystal World that is destroying the African jungle is not a conventional virus, but one which freezes matter into a timeless state:

Radek paused, collecting his energies with an effort. 'Tatlin believes that this Hubble Effect, as they call it, is closer to a cancer than anything else -- and about as curable -- an actual proliferation of the sub-atomic identity of all matter. It's as if a sequence of displaced but identical images of the same object were being produced by refraction through a prism, but with the element of time replacing the role of light." (The Crystal World)

The infected jungle landscapes he describes in the novel are worthy of a painting by Max Ernst, who transformed the Arizona desert with the keen eye of a timeless visionary. No wonder many of Ballard's early paperback collections of stories feature cover paintings that depict Tanguy-like amorphic blobs floating on the fused sands of psychic landscapes. What Ballard wrote was more like a Surrealist painting in prose, visions of vast subconscious shifts and the intersections where they touch the perimeter of conscious reality and every day life.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment