by Paul A. Schroeder Rodríguez

Jump Cut

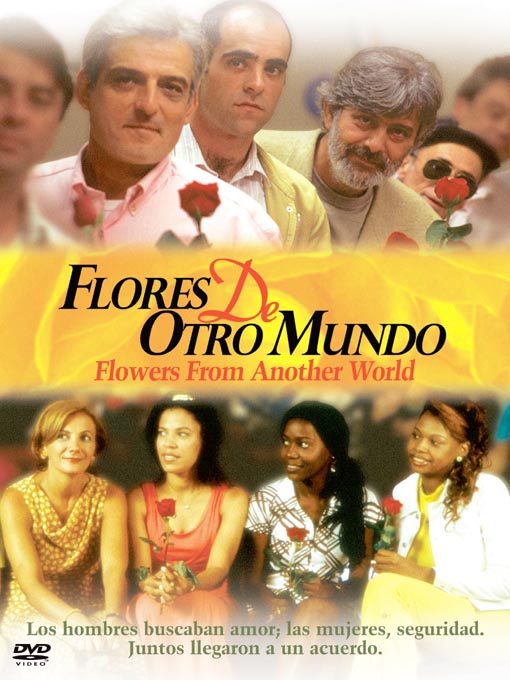

Flores de otro mundo (Flowers from Another World, dir. Icíar Bollaín, Spain, 1999) tells the story of Santa Eulalia, a small Castilian town that is losing many of its jobs and young people to corporate agriculture and the lure of big cities. The older men of the town, desperate to find mates, organize a three-day celebration for prospective single women from all across Spain. The women arrive in a single bus. About half of them are light-skinned Spanish women, while the other half is made up of younger, darker-skinned women from the Dominican Republic.

During a weekend of dancing, eating and drinking, two couples emerge from this get-together: one between Alfonso (Chete Lera), a plant nursery owner, and Marirrosi (Eleana Irureta), an economically independent Basque nurse from Bilbao; and another one between Damián (Luis Tosar), a farmer who tends to his land but also sells his labor-power to other landowners, and Patricia (Lissete Mejía), a Dominican mulatto domestic worker with two small children of her own. A third couple emerges later in the film, between Carmelo (José Sancho), the local building contractor, and Milady (Marilyn Torres), a young, college-educated, and sexually liberated black Cuban woman whom he brings back from one of his trips to the island, not as wife, but as his fiancée. In the end, only Damián and Patricia work things out through a marriage of convenience that reaffirms patriarchal structures of power, while Marirrosi returns to Bilbao and Milady hitchhikes her way out of rural Spain. In a sort of epilogue, the process begins all over again, when another busload of women arrives into town to be subjected to yet another round of legal and emotional transactions.

Flowers from Another World alternates between the celebration of women's economic and sexual liberation through the respective characters of Marirrosi and Milady, and the reaffirmation of patriarchal values through Patricia's incorporation into a nuclear, extended and ultimately, national family. The film sustains the ensuing tension between liberation and dependence through a combination of melodrama and realism, and in the end, resolves that tension in favor of Patricia’s narrative and the values of patriarchy.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment