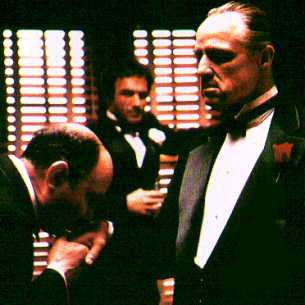

Revisiting the Godfather

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Although I vastly prefer Citizen Kane (1941) to The Godfather (1972), one facet of both films that gives me some pause—especially because I believe this facet has something to do with the current and unquestioned status of both movies as towering masterworks, not simply superb entertainments—is their worship of power, including their capacity to view corruption from a corrupt vantage point. Both movies are melancholy and wistful about their conviction that corruption is an inescapable part of American life in general and The American Dream in particular, and maybe I wouldn’t mind this attitude quite so much if its metaphysics weren’t so glib and absolute in its defeatism.

After all, accepting gangsterism along with its built-in denial as essential and inescapable parts of our condition has a lot to do what made the gangsterism/ denial of the Bush era so rampant, everyday, and taken for granted, at least until the possibility of overcoming it was implicitly posed by the Obama campaign. In his book GWTW: The Making of Gone With the Wind—–published the year after The Godather’s release, when some commentators were already touting it as that late 30s blockbuster’s natural successor—Gavin Lambert perhaps said it best: “When the most ruthless level of private enterprise becomes widely taken for granted, a film like The Godfather finds there are no questions left to be asked. Its characters exist in a nightmare which they (and the audience) accept as everyday reality.”

What Citizen Kane has that Orson Welles’ other films lack is the contribution of Herman G. Mankiewicz , whose caustic wit is valued by some for its comforting assurances about the inevitability of corruption. The more innocent and ultimately destabilizing view of corruption shared by Welles’ other films—that is to say, their lack of cynicism—surely has something to do with their failure to be fully assimilated into the American mainstream. For the Pauline Kael who viewed Kane as “kitsch redeemed”, the notion that The Godfather could be viewed as a different kind of kitsch rather than as a noble Shakespearean tragedy is never considered, because there are certain ideological givens about American violence and power, even at their most infantile and unreasoning, that are too serious to be scoffed at, especially when they’re bathed in “Rembrandt” lighting. By contrast, consider all the depictions of violence in such otherwise very different films as Renoir’s The Rules of the Game and Jarmusch’s Dead Man, which refuse the very possibility of violence having any kind of dignity whenever or however it occurs. Mythologies about macho power and the pride of wanton blood-spilling are arguably at the roots of what put George W. Bush twice into office, but this is something we’ve generally allowed ourselves to laugh at only after it’s too late to undo most of the damage.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment