The power behind the screen

Robbie Graham and Matthew Alford

The New Statesman

The output of Hollywood is intrinsically pro-establishment, and to understand why you have to follow the money

Baz Luhrmann's epic film Australia has been criticised by many, and most vociferously by Germaine Greer, for sanitising the country's colonial history. At the same time it has served the purpose of making Australia look like a great place to go on holiday - its release was accompanied by reams of coverage in the travel sections of newspapers and a lavish advertising campaign by the Australian tourist board. This kind of marketing is hardly new - throughout cinematic history, films have served political and social ends. But in order to understand the influences at play in Hollywood today it is still worth asking in more detail: what prompted 20th Century Fox to produce this kind of material? The answer becomes clearer when we learn that the studio's parent company is Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation, which worked hand in hand throughout the film's production with the Australian government. The arrangement works well for both parties: the government benefits from the increase in tourism, and in turn Murdoch will receive tens of millions of dollars in tax rebates.

This is just one example of how the content of Hollywood movies is determined not only by the demands of the box office and the vision of studio "creatives", but also by those higher up the economic food chain. Indeed, in its cinema power list the Hollywood Reporter placed Rupert Murdoch at number one. Steven Spielberg, at number three, was the only director in the top ten.

The economic structure of the film industry is built around the dominant Hollywood studios ("the majors"), each of which is a subsidiary of a much larger corporation. Each studio is therefore not a separate or independent business, but rather just one of a great many sources of revenue in its parent company's wider financial empire. So, just as 20th Century Fox is owned by News Corp, Paramount is a subsidiary of the media conglomerate Viacom. Universal is owned by General Electric/Vivendi, Disney by the Walt Disney Corporation, and so on. These parent companies are huge corporations, and their economic interests are sometimes closely tied to politicised areas, such as the armaments industry. They also depend on governments, which have the power to regulate in their favour and grant them tax breaks.

This is not to say that the content of a studio's films is determined entirely by the political and economic interests of its parent company; studio CEOs typically have considerable leeway to make the pictures they want to make, without any direct interference. But it is important to understand how and why Hollywood studios are tied into these wider corporate interests. At best, such interests contribute to a culture of conservative film-making. At worst, it is certainly not unknown for parent companies to take a conscious and deliberate interest in certain films.

To take one example: in 1969, Haskell Wexler - the cinematographer for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest - had considerable trouble releasing his classic Medium Cool, which riffed on the anti-war protests at the Democrat convention the previous year. According to Wexler, documents he has received under the Freedom of Information Act reveal that on the eve of the film's release, Chicago's mayor and others in the Democratic Party let it be known to Gulf & Western (then the parent company of Paramount) that if Medium Cool was released, certain tax benefits and other perks would be withheld.

In a telephone interview, Wexler told us that Hollywood's business leaders "have no conscience". He explained how this corporate agreement was made discreetly: "Paramount called me and said I needed releases from all the [protesters] in the park, which was impossible to provide. They said if people went to see the movie and left the theatre and did a violent act, then the offices of Paramount could be prosecuted." Although Paramount was obliged to release the film, it successfully pushed for an X rating, advertised it feebly, and forbade Wexler from taking it to film festivals. Hardly the way to make a profit on a movie, but certainly the way to protect the broader interests of the parent company.

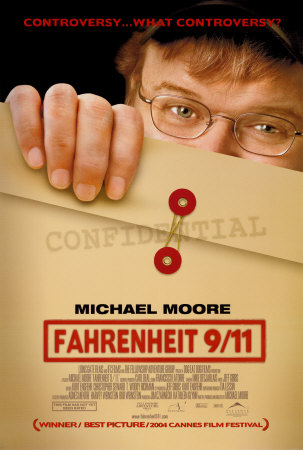

More recently, the Walt Disney Company tried to withhold Miramax's Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004), the Michael Moore blockbuster. Miramax insisted Disney had no right to block it from releasing the film since its budget was well below the level requiring Disney's approval. Disney representatives responded that they could veto any Miramax film if it appeared that its distribution would be counterproductive to the interests of the company. Ari Emanuel, Moore's agent, alleged that Disney's boss Michael Eisner had told him he wanted to back out of the deal due to concerns about political fallout from conservative politicians, especially regarding tax breaks given to Disney properties, including Walt Disney World in Florida (Florida's governor was the then-president's brother, Jeb Bush). Disney denied any such high political ball game, explaining that they were worried about being "dragged into a highly charged partisan political battle" and alienating customers.

To Read the Rest of the Article

No comments:

Post a Comment