by Suzidoll

Movie Morlocks (TCM)

The simplest yet most revealing filmmaking technique is the close-up, and yet it is a technique taken for granted because it is so familiar that we don’t notice it. Still, the close-up influences our sympathies and sense of identification with a character, making it a powerful technique. Recently, I have been thinking a lot about the impact of the close-up.

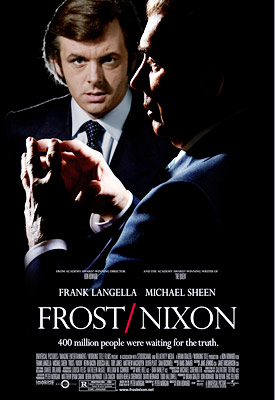

It started last week when I researched and wrote about I Want to Live, and I was struck by the number of close-ups of star Susan Hayward’s emotion-filled face. Director Robert Wise made good use of close-ups in the film to reveal what Hayward’s character is feeling and to influence us to sympathize with her. A few days later, I saw the ending of Sunset Boulevard, which ends with faded star Norma Desmond moving toward the camera and reciting her famous line, “I’m ready for my close-up, Mr. DeMille.” Then I saw Frost/Nixon over the weekend, which offers some thought-provoking ideas on the power of the close-up.

Frost/Nixon is based on the play by Peter Morgan, who adapted his work for the big screen. He also penned the scripts for The Queen and The Last King of Scotland. All three films revolve around historical figures at crucial moments in their lives, but they also share in common a point about the influence of the media in the construction and circulation of public image.

Frost/Nixon is all about the impact of television and its influence on making or breaking political leaders as well as journalists. In the film, David Frost and Richard Nixon are presented as having much in common, including their understanding of television. Though scorned by network and newspaper journalists as only a talk-show host, Frost bested them when he landed the Nixon interview. He thought that Nixon would make a compelling interview, and he believed he could get something out of Nixon that others couldn’t because he understood the power of the close-up from his talk-show experience. Nixon also knew it, because in the film he complains about his 1960s television debates with Kennedy, convinced that close-ups of the sweat on his upper lip cost him the presidency. But, Nixon did not learn his lesson, because he is tripped up by Frost, goaded into admitting that his actions during Watergate were not legal and that he inflicted damage on the American people. Then the camera lingers on his face as “the reductive power of a close-up” (a phrase used in the film) captures and encapsulates his regret, his downfall, and his realization that his political life is over.

Fictional films also benefit from the power of the close-up, though with different intent than television news or talk shows. Conventionally in films, the close-up produces a sense of intimacy between the viewer and the subject, revealing what a character is really feeling and eliciting our sympathy. Director Ron Howard uses close-ups to this effect throughout the film but in the final sequence, the use of close-ups is masterful. Frost and Nixon are shot in close-up much like a TV interview as the former bombards the latter with questions on Watergate. But, there are deeper layers of meaning in the close-ups. We see the effect of the questions on Nixon’s face as Frost asks them, and we see the impact of the answers on Frost’s face as he listens to the answers. Each knows what is at stake in regard to their futures in this interview, and each knows that only one of them will come out on top. Out of Frost’s mouth are questions about Watergate; on his face is the realization that his future rides on this interview. This is the story of Frost/Nixon, not the interview itself, and it is told through the close-ups. If you were to watch a video of the real interview, none of these other issues would be part of it.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment