by Jen

Skepchick

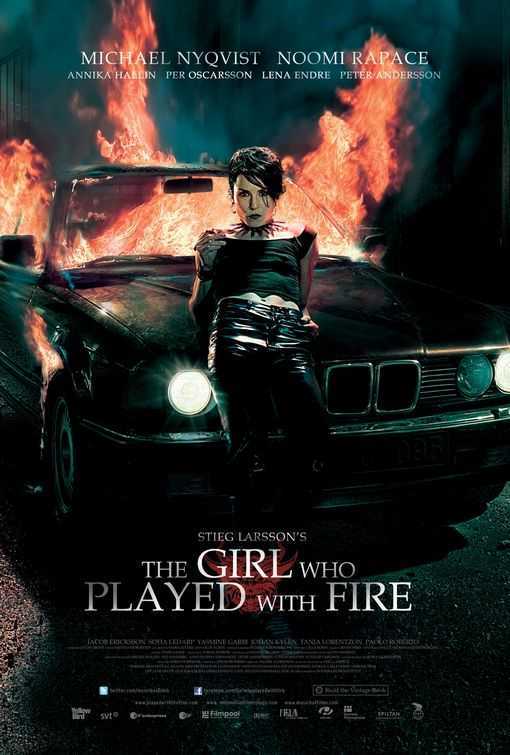

Like many another crime fiction junkie, I’m mildly obsessed with Steig Larsson’s Millennium trilogy. I pounced on the first book, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, when it first appeared in the States, and was rather thrilled to discover a good crime story with a startling unique and complex female character at its heart – an unfortunately rare occurrence. All too often, especially historically, women only occupy the backdrops of noir genre tales.

But beyond the story itself, the (anti-)heroine Lisbeth Salander has also seemed to find herself in the middle of a popular criticism debate about women, violence and the representation of both in art. The graphic depiction of both the violence – extremely sexual in nature – she is subject to and the violence she delivers in return has been the justification for critics to discuss whether or not her story deserves to be taken seriously or if it’s nothing but salacious drama only befitting the pulp from which tradition it springs.

Let’s say this immediately and clearly – misogynist imagery does not equal a misogynist work of art. That’s a lazy correlation too many readers, watchers and reviewers currently make about books, films and the like, and it’s simplistic and shallow. Rape scenes do not automatically mean sexual content is being using gratuitously. Descriptions of women being victimized do not immediately point to exploitation.

The impulse to label it as such is of course well-intended, and sometimes well-suited. It’s a sign of progress and, in general, a step in the right direction. But it’s not truly progress if it’s only an impulsive leap to the opposite end of the spectrum instead of a carefully considered conclusion about a terribly complicated and nuanced topic.

Let’s also be clear about this – it’s entirely possible for a book to be feminist without featuring a single feminist in it. Lisbeth Salander, for example, is not a feminist. She’s an extremely emotionally damaged individual focused on survival, although she seems to be at least on the path to improvement by the close of the trilogy. She’s a victim of systematic abuse and torture, and she’s committed to self-preservation and revenge by any means possible. She’s not a necessarily noble figure. She doesn’t have to be to prove Larsson’s point. The fact that she isn’t proves it even more successfully.

To Read the Rest of the Essays

No comments:

Post a Comment