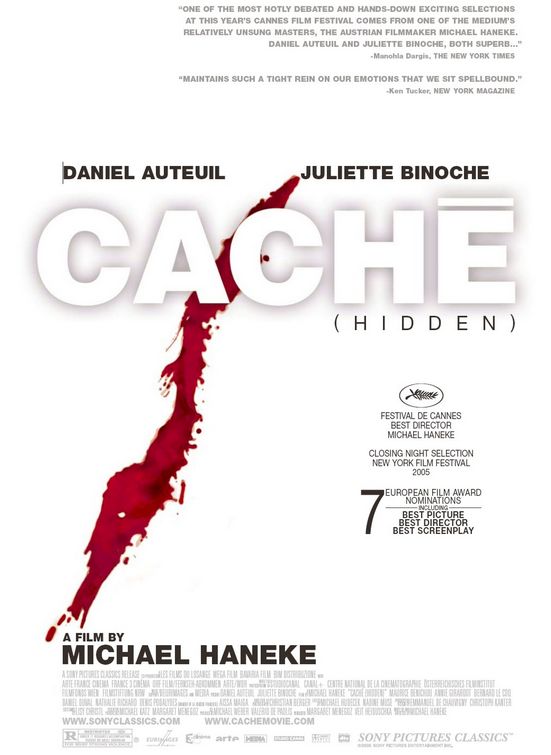

Gaze, Suture, Interface: The Suicide Scene in Michael Haneke’s Caché

Seung-hoon Jeong

Cinephile (The University of British Columbia)

Georges (Daniel Auteuil), a host of a high-brow talk show, receives suspicious videotapes that display the peaceful façade of his upper middle class house. Nothing is clear in this CCTV footage in which there is ostensibly ‘nothing happening’: who has been watching his family, and why? Subsequent clips lead him to his childhood home and to an unknown apartment, which turns out to be the dingy place of his adopted, then abandoned, Algerian brother Majid (Maurice Bénichou). This forgotten ‘other’ confronts Georges with an uncomfortable truth from the past: young Georges’s jealousy forced Majid to be sent off to an orphanage, whereafter Majid had to survive without the educational and social benefits given to Georges. The nature of the video thus changes from provocation to evocation, from surveillance to reminiscence. Michael Haneke’s Caché [Hidden] (2005) uncannily uncovers this hidden trauma that resurfaces in the present. But my primary question is simple: why video?

Let me call this video an ‘interface’. Technically meaning the contact surface between image and spectator, the notion can be applied to the camera, the filmstrip, and the screen. That such a cinematic interface appears onscreen might not merit discussion in many cases, but it can play a central role in the narrative, whose unity is often thwarted and destabilized by the interface image. The subjectivity of characters or spectators can also be shaped or shaken through their encounters with the interface-within-the-film. A diegetic interface may then affect the ‘perception’ and ‘memory’ chain along which ‘image’ and ‘subjectivity’ are interconnected. Caché seems ideal for a case study in this regard, not only because of its video insertions, but because of the consequent revelation of perceptual and mnemonic mechanisms. What follows begins with a close analysis of a scene that exposes these mechanisms and thereby inspires us to explore, even expand the theoretical implications of the interface.

Among many significant scenes, I take Georges’s second visit to Majid’s flat as a kernel of the film’s structure. Its impressiveness, of course, bursts out of Majid’s sudden suicide; Majid lets Georges in, talks for a second, takes out a knife as Georges slightly falters, and slits his own throat, leaving no room for anticipation. The abruptness of this action marks the abruption of Majid’s emotion: a remarkable calmness and gentleness, not usually found in revenge suspects. It is rather Georges, the white Parisian intellectual, who has always lost his temper in front of his lower class, dark-skinned brother (and later, in front of Majid’s son, too); this Algerian outcast has reversed the standard image of the brutal invader of the bourgeois family like the De Niro figure in Cape Fear (Martin Scorsese, 1991). By killing himself, Majid releases something repressed beneath his tranquil face and fractures the peace of both his banlieue home and Georges’s bourgeois life. The flash of his blood sprayed onto the wall visualizes this fracture like an unstitched slash; the blood slowly exuding from his head onto the floor insinuates that this trauma will only grow like a nightmare in Georges’s memory.

In view of other scenes, Majid’s bloodstain on the wall triggers a déjà-vu that allows us to retroactively recognize the drawings sent to Georges (of a child vomiting blood) as forewarnings of this suicide. And through the same logic of ‘deferred action’ (Freudian Nachträglichkeit), this bloody event serves to repeat the film’s first instant flashback, prompted by a reverse-action tape, of young Majid coughing tubercular blood by a window, and the childhood trauma staged in Georges’s nightmare: Majid kills a cockerel, which also leaves a sharp blood mark, and he approaches Georges with the bloody hatchet. This killing was in fact orchestrated by Georges, but he told his parents that Majid had wanted to scare him, a joking lie that, along with Majid’s tuberculosis, ultimately resulted in Majid’s expulsion. However, only through recurrent visual traces after the fact does that original scene manifest its latent meaning as Georges’s original sin. The question would be how guilty and responsible the child and/or adult Georges is for that tiny ‘twisted joke’ that had lifelong repercussions/consequences for Majid. One may conclude: “Georges’s refusal as an adult to acknowledge the effects of his earlier actions suggests a parallel with the postcolonial metropolitan who is neither wholly responsible for, nor wholly untainted by, past events from which he or she has benefited” (Ezra and Sillars 219).1 Or, Majid’s suicide might bring a deep, if guilty, pleasure to a deeply ‘twisted’ xenophobe European: “the comforting idea that the colonial native can be made to disappear in an instant through the auto-combustive agency of their own violence” (Gilroy 234).

To See the Video of the Scene and Read the Rest of the Analysis

No comments:

Post a Comment