by Atticus Narain

Dark Matter

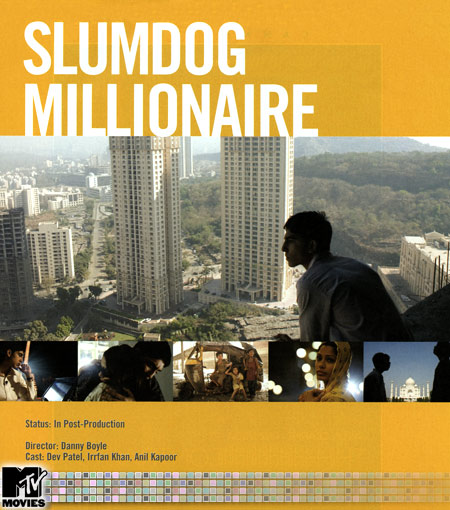

Sound bites: poverty porn, slum tourism, imperialist guilt flick, post-colonial inequalities continued, Bombay’s underbelly revealed- revelled, brilliant, feel good movie, accurate portrayal, gross misrepresentation, a visual Lonely Planet guide to Mumbai, an (anti-)Indian movie, Bollywood mania. On television Boyle takes questions from enthusiastic BrAsians; in The Guardian Rushdie laments the “impossibility on impossibility”; and angry Amitabh Bachchan writes back – sounds jealous; my own contribution would be Angelina Jolie and Madonna tussling at the Oscars over adopting the movie’s child actors.

The American and British film industries’ acclamation of Slumdog Millionaire has raised much media debate. Issues of authenticity, cultural ownership,‘burden of representation’, the nationality of its director, its content and stylistic aesthetics, and Eurocentric and/or re-Orientalist visions, have created a vast contact zone for analyzing cinema, identity, and nationalism. None of this is new of course – contention of where Kurosawa and Ray belong continues; Spike Lee’s criticism of Quentin Tarantino’s use of Afro-American linguistics replays these debates – albeit with different histories of race, empire and exploitation. Using child actors as allegories of post-colonial development is characteristic of new national cinemas. This is brilliantly done in Amir Naderi’s The Runner; Salam Bombay is a little geographically closer, and numerous Indian socials of the fifties and sixties deployed children as central to narrative development and critique.

Slumdog Millionaire does not confirm to the contexts of such debates usually associated with World – Third – Alternative – cinemas, certainly not in the political sense that these cinemas are often discussed. Every now and again a film’s popularity transcends the categories accorded them and is propelled to a much higher and holy accolade. Slumdog Millionaire is City of Joy for the twenty-first century, informed by an anthropological attempt at readdressing inequalities of representation by “giving” the camera to the Other and erasing the need for white protagonists – well almost. If Boyle’s ethnicity was different would all this discussion be taking place? What happened to Gurinder Chadha’s aesthetic and agenda? Forced to succumb to funding desires of reproducing the East for the West- Bride and Prejudice- or producing minority narratives that tick every possible identity ‘clash’? Gentle, unassuming, had never even been to India prior to filming, Boyle does it better!

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment