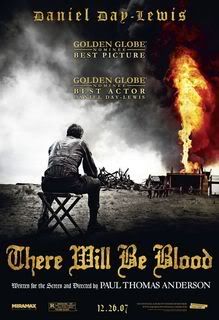

Paul Thomas Anderson's There Will Be Blood: No Gods, Just Monsters

By Norman Wilner

I really have just two words to say about Paul Thomas Anderson's There Will Be Blood: "God" and "damn".

It's nearly three hours long, but it moves like a shot. It's a period piece that's utterly contemporary in its construction. It's a character study of a monster — two monsters, actually, locked in a perpetually hubristic battle with one another for the bragging rights to all creation.

Or at least that's where it ends up. At first, There Will Be Blood just looks like a father-son story, following an oilman named Daniel Plainview — played by Daniel Day Lewis as if he was the bastard son of John Huston in Chinatown and Mr. Burns from The Simpsons — who carts a young orphan boy from one small California town to the next, as he negotiates for the drilling rights that will make him very, very wealthy. (The boy makes a great prop; with a child at his side, Daniel looks like a family man, rather than a robber baron.)

But then we meet the other monster, a young preacher named Eli Sunday whom Daniel and his lad encounter in the tiny community of Little Boston. The achingly pious Eli — presuming himself to be a civic leader — demands an honorarium for his fundamentalist church and a say in Daniel's affairs. This, as they say, does not sit well, a rivalry that stretches out over decades, and which could easily be read as an unsettling allegory for America's perpetual conflict between commerce and faith.

Anderson established himself as a natural-born filmmaker with Boogie Nights, Magnolia and Punch-Drunk Love, but There Will Be Blood is an evolutionary step beyond his previous work. As good as the earlier films are — and they are very, very good — there's a sort of shine to them. Whether it's the fluidity of the Steadicam shots in Boogie Nights, or the glistening streetscapes of Magnolia's Los Angeles, or Punch-Drunk Love's bursts of impressionistic color, they're movies that were made to be noticed; Anderson can't help drawing our attention to his accomplishments. They're somehow ... boastful.

To Read the Rest of the Appreciation

Paul Thomas Anderson's There Will Be Blood: To Be and To Have

By Jorge Morales

In one scene from There Will Be Blood, oil baron Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) asks, startled as he studies a map with one of his lackeys, why there is a territory that does not belong to him. "Why isn't it mine?" he rebukes. It's not that Daniel Plainview wants to take over the land, but that he is incapable of establishing any distance between what he has and what he wants. That is the difference between greed and envy: Plainview does not covet another's property; he considers that no one has the right to possess something that he desires. One cannot feel envious if one despises or scorns the others' existence. Not only does Plainview not want what belongs to another; he does not want that person to exist. It is an even more egocentric and perverted thirst for power than that of a despotic entrepreneur who just wants to accumulate wealth. Plainview is a predator, someone who wants to trample without resistance. At some point he says something like "I don't want anyone else to be successful". The funny thing is — and here lies the great merit of the complex personality designed by Paul Thomas Anderson — that Plainview is presented early in the film as a sensible, hard-working person who is able to give and to receive affection. And it's not just a performance to fool the people he wants to swindle out of their lands, by selling his relationship with his son (who he introduces as his partner). Plainview's love is honest and intimate but, as it is later shown, not at all faithful and inalienable; it goes through crises each time his interests are at stake. If he must choose between an oil well in trouble and his ill son, he does not hesitate for a second about leaving the boy for later. In that sense, the film's title can both refer to the subterranean violence that never manifests explicitly and completely (such as Plainview's terrifying spoken threats), and to the weakness of filial bonds, which open and close up like oil wells.

To Read the Rest of the Statement

No comments:

Post a Comment