By Paul Ryan

Criterion

Some years ago, I screened Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 film Don’t Look Now for a group of international students who were learning English. Rarely have I seen an audience more engaged by what they were watching. We discussed the film afterward, and I was delighted to discover that, despite their limited understanding of the language, these young people had not only grasped the essentials of the fragmented narrative but also picked up most of the nuances of the story. Of course, it should come as no real surprise that Roeg, who first distinguished himself as a cinematographer, would be able to convey a story in visual terms, but it was that audience’s response to the subtleties of the characters’ emotions that most underlined his achievement. The central scene of lovemaking prompted the first, hesitant remark: “It is beautiful when they try to make new baby.” It was obvious that these were not passive spectators. Where some would have seen a thriller, they had observed a tragedy.

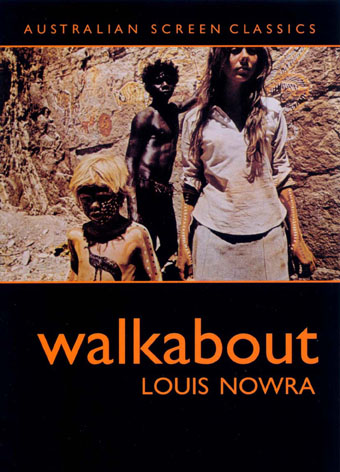

Don’t Look Now should be proof enough that, more than any other British filmmaker of his generation, Roeg has the ability to create pure cinema. But the finest example of his gift remains Walkabout (1971), his first solo outing as a director. He had codirected and photographed Performance (1970), but it is generally accepted that, while the look and the pace of that film owe much to Roeg, its “authorship” can be more properly ascribed to its screenwriter, Roeg’s codirector, Donald Cammell. Walkabout is entirely Roeg’s own. Based on the 1959 novel The Children, by James Vance Marshall (a pseudonym for the English writer Donald G. Payne), Walkabout is, like its source material, essentially a coming-of-age story. In Marshall’s novel, the two white children are survivors of a plane crash, and the core of the tale is their journey through the Australian outback and relationship with an aboriginal boy who befriends them—as it is in the film. The book has long been regarded in Australia as a children’s classic along the lines of The Swiss Family Robinson, but Roeg and his screenwriter, Edward Bond, made small, significant changes that took the film into harsher territory.

The first of these was to eliminate the plane crash (initially, perhaps, to avoid similarities to the opening of Peter Brook’s 1963 adaptation of William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies). They replaced it with the suicide of the children’s father—thus heightening the violence of the opening and personalizing the children’s sense of abandonment. Also heightened was the children’s curiosity about one another, which took on a deeper element of sensuality and, in the case of the girl and the aboriginal boy, nascent sexuality. In a justly famous sequence, the girl swims naked in a lake, and while this can be interpreted as her need to clean and refresh herself in midjourney, it has an unmistakable element of display. Toward the film’s end, it is the turn of the young aborigine to display, by means of a sexually charged ritual dance directed at the girl. The girl’s fearful rejection of him leads to another major change from the novel. There, the native boy dies from a virus to which he would not have been exposed if not for his encounter with these outsiders; in the film, the young man takes his own life. A film with two suicides and a delicately sensual nude scene was never destined for the label of “children’s classic,” and yet one can sense that Roeg has trust in the reaction of an adolescent audience, for he is speaking the truth of adolescence to us all.

The film had a curious gestation. While working as cinematographer on François Truffaut’s only English-language film, Fahrenheit 451, in 1966, Roeg met the producer Si Litvinoff, who had recently optioned the Anthony Burgess novel A Clockwork Orange. The two met again, and became fast friends, when Roeg was photographing Richard Lester’s 1968 Petulia, and when Litvinoff discovered that Roeg was eager to turn to film direction, he started seriously considering giving him his chance with A Clockwork Orange. Soon afterward, Litvinoff went into partnership with the clothing manufacturer turned producer Max Raab, who was keen to finance A Clockwork Orange and was in favor of Roeg as director. But the new team turned first to Gerry O’Hara’s drama All the Right Noises (1969), and while Litvinoff was continuing to develop the script of A Clockwork Orange with Burgess and screenwriter Terry Southern, he discovered that Roeg had become obsessed with the James Vance Marshall novel, and had approached a writer he greatly admired, the British playwright Edward Bond, to work on a script. Litvinoff helped Roeg acquire the rights to the novel, and Raab agreed to finance Walkabout.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment