by Shakuntala Banaji,

Centre for the Study of Children, Youth & Media, UK

Participations

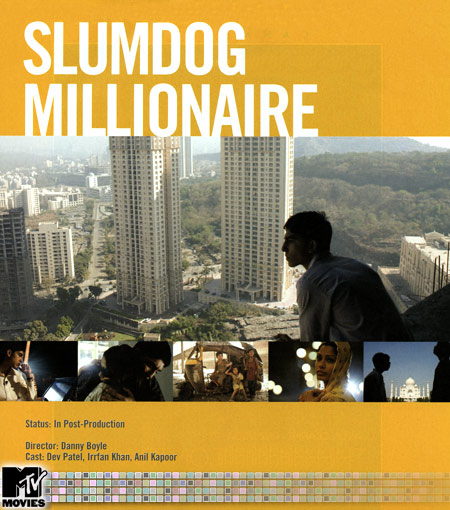

Slumdog Millionaire (Dir. Danny Boyle, 2008) is now best known for winning numerous Awards at the Baftas, Golden Globes and the Oscars. After being publicly championed by an unprecedented number of film critics, it caused something of a media sensation when celebrities in Bollywood and some (but not all) viewers in India publicly labeled it exploitative and unfair to India and Indians. Told in flashback from the point of view of a young man, the film narrates the story of two brothers from a shantytown in Bombay, who choose different pathways in life. In the opening sequence of the film, one of the brothers has reached the final of the much-vaunted TV quiz show, the Indian version of ‘Who wants to be a Millionaire’. Arrested, apparently for cheating, Jamal Malik ‘explains’ to his police interrogators how it is possible for someone like him, a slum child with little formal education, to know the answers to the most seemingly esoteric questions: he has learned the answers through bitter experience. And in the process of recounting these, he opens for the audience (what is displayed unashamedly by the film as) a window on the world of two Muslim children born in a Bombay shantytown in the 1980s. Via fast-paced sequences full of jump cuts – depicting communal riots, professional begging and child molesting gangsters – the boys and the camera travel across India and back again. They return in search of an old girlfriend as Bombay’s/Mumbai’s economy goes neo-liberal and gated communities spring up, isolating the rich from the poor. In tandem, the younger brother, Jamal, stays honest, innocent, hard-working and loyal – a tea-boy in a call centre; the older brother becomes a gangster’s lackey, corrupt and aggressive, taking the quickest possible route to what seems like financial success.

A viewing of the film during a year of media hype, followed by a series of random but heated discussions about it, crystallised into an urge to discover whether and how different kinds of knowledge and experience – about cinema, about Hindi cinema, about India, about Bombay, about urban poverty (Indian style) – played into critical responses to the film, by viewers or by established film critics. Saying that the same film and the same set of circumstances can call up wildly different even contradictory viewpoints from people, or from the same person at different times should no longer be much of a surprise. Meaning does not reside solely in media texts; this has been established over the decades via painstaking theoretical critique and empirical scholarship (see, among others, Austin 2002, Buckingham 1993, Barker and Brooks 1998, Mankekar 1999 and Staiger 1999). Although there are still those new to the subject who might write as though texts are all-powerful and hold ultimate sway, enough has been done to challenge a text-centric understanding of meaning and effects to obviate the necessity for another paper on this topic. What is interesting about people’s reactions to this particular film is not, in fact, the divergence of opinion per se. What is intriguing however is, first, the vehemence and types of the feelings called forth by what might seem a fairly prosaic rags to riches story, albeit set in a (to most Western audiences) exotic setting: delight and jubilation, inspiration, tears, disgust, anger and humiliation are only some of the emotions expressed by those who watched it. Second, and more confusingly, perhaps, it was read as an educational – almost an ethnographic – tale by some re/viewers, a contrast to Bollywood glitz and to the mawkish sentimentality of documentaries about India. Additionally, and more problematically, perhaps, opinions expressed about the film contained tropes of quasi-orientalist (Said 1978) or re-orientalist (Lau 2007) cultural and political discourse. Indeed, the quaint assumption of an ethnographic subject when a film or book happens to feature non-white and non-western protagonists is a classic feature of such discourse in relation to fiction genres. In a fascinating paper delivered on this subject, Ellen Dengel-Janic argues that ‘[w]hat the film negates and helps to mask in a pleasurable visual manner is a translocated fear of poverty and the abject…. the film’s appeal reflects not only the West’s exoticism of India, but also its repressed fear and paranoia of becoming abject and poor’ (2009: NP). But given the wide range of viewers who ultimately encountered the film, can such a critical reading be sustained? Understanding the combinations of circumstance and experience, contextual and technical knowledge and generic expectation that led to particular discourses or technical sequences in films being picked up and enjoyed or selectively critiqued has been the aim of much of my work on Hindi cinema to date (see Banaji 2006 and 2008) and remains at the core of this paper. However, even these combinations do not capture fully the investments people have in their judgments about films or indeed the complexity of the emotional and cultural histories that inflect these judgments.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment