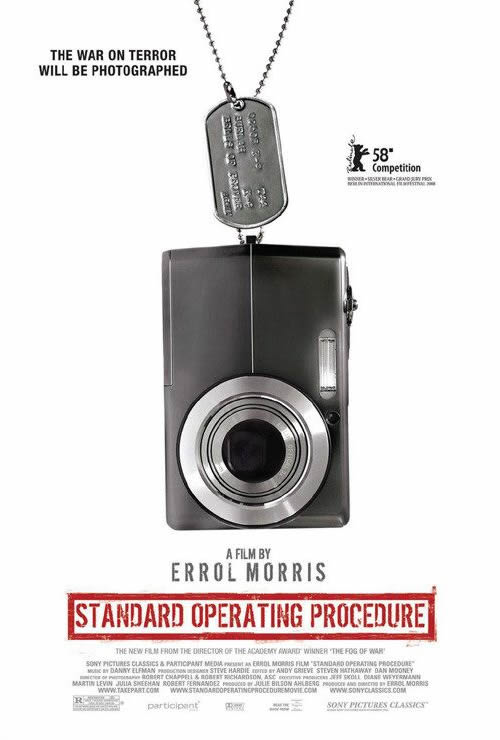

Errol Morris: "The Photographs Actually Hide Things From Us"

By Sean Axmaker

Green Cine

How did you convince the five MPs to consent to be interviewed?

Not just the five; everybody was difficult. I suppose that the easiest of all the people I've interviewed – well over twenty people, lots of interviews that are not in the movie – the easiest was Janis Karpinski. I worked as a private detective years ago and I was starting a new case, one of the first cases I worked on, and I said, "Who should I interview first?" And my boss said, "You should always pick the people who have been fired because they are always willing to talk." And that is very, very sound advice.

Janis Karpinski was fired and demoted by Bush and she'd been making the rounds. This all started because my cameraman saw an interview with her on C-SPAN and said, "You should check this out. I think you will be interested." And I brought Karpinski to Boston and we did a 17-hour interview over two days, this quite extraordinary interview where Janis Karpinski started out angry and got angrier and angrier and angrier. I suppose this goes into the DVD extras category, but at one point she made a comparison between Lynndie England and herself and Jessica Lynch. I suppose it's these pictures of American women in the military, how the story changed from the damsel in distress to these evil witches who caused perhaps the demise of our war effort in Iraq. And the way Janis put it, I will never, ever forget. She said, "They needed another face of American women in the military in Iraq and it was Lynndie England and it was me."

This is a very complex, convoluted story on so many, many different levels. I think it is, in many ways, a story about American women in the military. I think that's one of the things about the photographs that made the photographs particularly strange, particularly appalling, particularly perverse. I've often imagined, when [Charles] Graner was taking those pictures, of his 90-some-odd pound, twenty-year-old girlfriend, holding that leash on that the prisoner known as Gus, he was in some very deep sense reenacting American foreign policy.

You bring up what I think is a central point. It's about halfway through the documentary when Lynndie England tells us she was 20 when all this happened.

And turned 21.

That's not something that was part of the story in the media when it broke. We didn't think about how young she was, but in fact there were a lot of young soldiers and MPs there and not a lot of strong leadership, or at least responsible authority.

There was authority. There were commanding officers, there was a chain of command. I often think of Javal Davis and Sabrina Harman talking about their first day on the tier. This is mid-October, 2003. They walk in on something well before they arrived on the scene: prisoners in stress positions, panties on their heads, sleep depravation, stripped nude. Often the policy had them stripped nude by a female interrogator or a female MP because that would be more humiliating. Even [Tim] Dugan, the contract interrogator, talks about how he goes to work: first day at Abu Ghraib, two female interrogators have stripped this Iraqi prisoner nude, and he goes and asks his supervisor: "Excuse me, but should they be doing this?" He says, "Well they can do it, you can't. But they can do this, yes." It's part of policy!

Thus the title: Standard Operating Procedure.

I mean, to think that this happened because of a few rogue soldiers flies in the face of just overwhelming evidence. This is not a political debate, this is not left versus right. We're talking about evidence here. When one of the prosecution witnesses, Brent Pack, tells you that the iconic picture of abuse is standard operating procedure, that's not me saying it's standard operation procedure, that's Brent Pack, Army C.I.D. and photo expert, saying it's standard operating procedure. I like Brent Pack a lot. He's an uncommonly decent and helpful guy.

You mentioned that you had once been a private investigator yourself. Pack is the detective part of the movie, sorting through the evidence to piece together the timeline, but it's what the evidence reveals that is most interesting, the parts of the story that are not being covered in the media. Your film keeps returning to the photos.

Yes. They're at the center of the story. Absolutely.

What I think is so amazing about that is that, through the course of the film, you deconstruct the photos. You interview all these people, you uncover all this evidence from these witnesses, yet the only crimes that were prosecuted were those that were photographed, the ones that had the visual evidence, the ones that were seen by the public.

But it gets even worse than that. I have this essay coming out in the New York Times this week on Sabrina's smile, the photograph of her with her thumb up, the smile and the body of [Manadel] al-Jamadi. Now I remember seeing this photograph for the first time and thinking, "God Lord, what is this? It's monstrous."

She didn't kill him. A CIA interrogator either killed him or was complicit in his death. The brass of the prison was involved in a cover-up. In the log, he's described as Bernie, from Weekend at Bernie's, the body which people have to get rid of. It's an inconvenience because they don't want to be, in any way, implicated in his death. He's the hot potato being shuffled about.

Sabrina takes these photographs as an act of civil disobedience, to provide evidence of a crime. In her letter to Kelly, immediately following this whole deal, she says, "The military is nothing but lies. I took these pictures to show what the military's really, really like." And here's the weirdness of it all. The people responsible for al-Jamadi's death, the people responsible for covering up a murder, skate. Sabrina spends a year in jail.

I think this is the heretical thing. It's not just that the photographs direct us in a certain way, but they actually hide things from us. They make us think that we know a story when in fact we don't know the story at all, or we know the wrong story. It's endlessly fascinating to me and I would like to set the record straight. That represents to me an incredible miscarriage of justice. Taking a picture of a body to expose the military and to expose a crime, to me, is not a crime. Murder is a crime.

To Read the Rest of the Interview

No comments:

Post a Comment