by Konrad Ng

Flow TV

In “Talking About a Revolution (for a Digital Age),” New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis reflects on the evolution of American independent cinema in the wake of its “Hollywood hangover.” She contends that starting in 1993, the emergence of a “studio-indie infrastructure” transformed American independent cinema into a micro Hollywood industry that allowed some filmmakers to go “from Sundance to Scorsese.” However, she contends, this studio-indie film system has been “rocked by seismic changes – including downsized companies and emerging technologies” and giving way to a leaner, non-studio version of independent cinema. Dargis states that American independent cinema is being shaped by the rise of an interactive, digitally assisted “Do-it-yourself” (D.Y.I.) film culture. She points to how digital media forms of self-distribution and promotion have enhanced independent cinema’s important connection with audiences to create “a more complex, interactive and personalized relationship.” She states that the vitality of American independent cinema also depends on “the cultivation of younger patrons who are used to receiving much if not all of their entertainment at home and on hand-held devices” and making them into “active participants in the movie and its meaning.” For Dargis, the ebb of Hollywood’s role in independent cinema means that youthfulness and digital D.Y.I. interactivity are forming the conditions for American independent cinema’s next generation of iconic films and filmmakers.

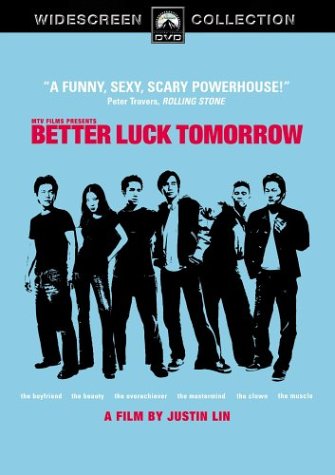

Manohla Dargis’s article prompts me to think about filmmaker Justin Lin. Lin’s young film career is characteristic of the studio-indie age before its current malaise. Lin went to great lengths, personal sacrifice and debt to make his solo debut feature film, Better Luck Tomorrow, a film that premiered at the 2003 Sundance Film Festival to critical acclaim, a distribution deal with MTV Films and eventually, work as a director for studios such as Universal Pictures and Touchstone Pictures. My interest in Lin lies not in discussing his merits as a filmmaker. Rather, I am interested in how Lin’s trajectory embodies a set of digital age D.Y.I. generational tactics and strategies that emerged in a tradition of American cinema that has rarely found studio traction during independent cinema’s Hollywood bubble: Asian American cinema. After Lin made his Hollywood films, Annapolis (2006) and The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (2006), he returned to the world of the independent cinema to make the film, Finishing the Game (2007). The promotional campaigns for Better Luck Tomorrow and Finishing the Game embody the practices of digital age independent cinema culture discussed by Dargis, but Lin’s strategy is both unique and instructive, I suggest, for its form of Asian American political and cultural engagement. The strategies behind Lin’s films reveal aims that went beyond simply “breaking out” as most independent films aspire to do. Instead, Lin’s films became platforms for community organizing and engagement that sought to impact the meaning of Asian America in American film history and popular culture.

To be sure, both films are notable for how they critically explore race and representation and both took refuge in the lean, but creatively free world of independent cinema. Better Luck Tomorrow tells the story of a group of high school students who use their status as academic overachievers to mask and enable their illicit activities. Finishing the Game is a mockumentary about the search for an actor to replace Bruce Lee after his unexpected death during the filming of Game of Death (1978). When considered through the lens of Asian American representation, each film becomes a provocative commentary on stereotypes, genre and cinema. As non-studio productions, Lin maintained a creative commitment to an Asian American agenda that included, among other objectives, introducing a range of multi-dimensional Asian American characters and showing how Asian America is a commercially viable audience and source of cinema. This creative independence and ethical imperative became inter-articulated with the political and cultural tactics behind the digital D.Y.I. promotional campaigns for the films. I want to save a fuller discussion of Justin Lin for another time and focus on just some of the practices that emerged from Lin’s films. My tack in exploring this topic is to study selected new media activities as part of a larger example of Asian American community organizing and political engagement in the digital age. In this regard, Lin is a pioneering figure.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

No comments:

Post a Comment