"My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel--it is, above all, to make you see." -- Joseph Conrad (1897)

Friday, July 30, 2010

Uses of a Whirlwind: Movement, Movements, and Contemporary Radical Currents in the United States

I recently received this extensive collection of essays Uses of a Whirlwind: Movement, Movements, and Contemporary Radical Currents in the United States on contemporary radical organizing and action... below is the announcement for the book and here is the introduction that is available online: "Sowing Radical Currents in the Ashes of Yesteryear: The Many Uses of a Whirlwind"

Valerie Strauss: 'The Dumbest Thing' in Education Thinking -- Obama, Education, Snooki, Civil Rights and Bryan Bass

'The Dumbest Thing' in Education Thinking: Obama, Education, Snooki, Civil Rights and Bryan Bass

by Valerie Strauss

Washington Post; Reposted on Common Dreams

...

In June, 2010, Bryan Bass, the principal of Brooklyn Center High School in suburban Minneapolis, was fired.

Brooklyn Center is one of 34 schools on Minnesota's list of "persistently lowest achieving" schools. The state education commissioner says that the federal School Improvement Grants (SIG) program will give the state the opportunity to "really dig deep and try to solve the educational issues" in their failing schools.

For Brooklyn Center, like all schools targeted under the SIG program, receiving federal funding for reform efforts required firing the current principal.

Brooklyn Center High School enrolls about 800 students, three-quarters of whom are low-income and children of color. Roughly 14% of the students have learning disabilities, and about 20% are English Language Learners. The school offers a strong arts magnet program, and an International Baccalaureate program, making it a popular open-enrollment school. Though 82% of students who enroll, graduate, the school has some of the lowest assessment scores in the state.

Bryan Bass has been principal at Brooklyn Center for four years. Under his leadership, the number of suspensions each month fell from 45 to about 10. The number of graduates who went on to college doubled from 35% to 70%. Student mobility dropped from 33% to 26%.

Bass and Superintendent Keith Lester also worked tirelessly on meeting another need of the school community. One wing of the school was recently turned into a one-stop medical and social service center. The center is equipped to care for any student or school-age resident in the area.

With or without health insurance, students have access to dental, vision, mental health and medical services right in the building. The need for wrap-around supports for students immediately became apparent: In the first year, 70% of students who were tested were found to have untreated vision problems. By building a network of existing providers and agencies, identified needs were met. Children who needed glasses were given them. The clinic offers a therapist to help students work through emotional issues.

A social service agency has an office in the clinic that helps students' families find health insurance.

"Overnight - overnight, it absolutely decreased the amount of behavioral issues," principal Bass told a local reporter about the new school-based center. "By eliminating barriers, you start to really understand what's in the way of students getting to learn."

The future of Brooklyn Center High School's health and social services center is not guaranteed under the federal grant program. One thing was guaranteed, though. The school's energetic principal had to go, as a condition for participation in the SIG program.

Superintendent Lester is frustrated with the rigidity of the federal grants program: "I think that's the dumbest thing I've seen coming out of education in my years in education," he said.

To Read the Restof the Commentary

by Valerie Strauss

Washington Post; Reposted on Common Dreams

...

In June, 2010, Bryan Bass, the principal of Brooklyn Center High School in suburban Minneapolis, was fired.

Brooklyn Center is one of 34 schools on Minnesota's list of "persistently lowest achieving" schools. The state education commissioner says that the federal School Improvement Grants (SIG) program will give the state the opportunity to "really dig deep and try to solve the educational issues" in their failing schools.

For Brooklyn Center, like all schools targeted under the SIG program, receiving federal funding for reform efforts required firing the current principal.

Brooklyn Center High School enrolls about 800 students, three-quarters of whom are low-income and children of color. Roughly 14% of the students have learning disabilities, and about 20% are English Language Learners. The school offers a strong arts magnet program, and an International Baccalaureate program, making it a popular open-enrollment school. Though 82% of students who enroll, graduate, the school has some of the lowest assessment scores in the state.

Bryan Bass has been principal at Brooklyn Center for four years. Under his leadership, the number of suspensions each month fell from 45 to about 10. The number of graduates who went on to college doubled from 35% to 70%. Student mobility dropped from 33% to 26%.

Bass and Superintendent Keith Lester also worked tirelessly on meeting another need of the school community. One wing of the school was recently turned into a one-stop medical and social service center. The center is equipped to care for any student or school-age resident in the area.

With or without health insurance, students have access to dental, vision, mental health and medical services right in the building. The need for wrap-around supports for students immediately became apparent: In the first year, 70% of students who were tested were found to have untreated vision problems. By building a network of existing providers and agencies, identified needs were met. Children who needed glasses were given them. The clinic offers a therapist to help students work through emotional issues.

A social service agency has an office in the clinic that helps students' families find health insurance.

"Overnight - overnight, it absolutely decreased the amount of behavioral issues," principal Bass told a local reporter about the new school-based center. "By eliminating barriers, you start to really understand what's in the way of students getting to learn."

The future of Brooklyn Center High School's health and social services center is not guaranteed under the federal grant program. One thing was guaranteed, though. The school's energetic principal had to go, as a condition for participation in the SIG program.

Superintendent Lester is frustrated with the rigidity of the federal grants program: "I think that's the dumbest thing I've seen coming out of education in my years in education," he said.

To Read the Restof the Commentary

Greg Mosson: Ars Poetica -- A Case for American Political Poetry

Ars Poetica: A Case for American Political Poetry

by Greg Mosson

The Potomac

Why should poets address political issues, ask some critics with arched disapproving eyebrows, and then often they answer that politics its too timely a subject for quality poetry. Question and the answer miss the point. First of all, any subject matter is timely in poetry. Robert Frost’s classic second book North of Boston is almost entirely comprised of narrative dialogues of people right in the middle of things, and yet the poetry he crafted with it will remain relevant as long as the English language does. The poet in the classic sense always faces the technical difficulty of making life at hand relevant to the teeming generations. The question is much more interesting if reversed: Why should poets exclude political and social issues from their poetry?

If poetry is “a statement in words about an experience,” to use critic Yvors Winters’ definition in The Function of Criticism; then why should the political aspects of “experience” be excluded from poetry? Helen Vendler in her book Poets Thinking sees “poets as people who are always thinking, who create texts that embody elaborate and finely precise (and essentially unending) meditation.” While 20th century history shows many examples of totalitarian governments oppressing artists who dare to address state matters in their work, why should poets on their own narrow their thinking to the nooks and crannies of just personal space (as if personal space can be so cut off from other people and the social and natural worlds). Lastly, if poetry is “the record of the best and happiest moments of the happiest and best minds,” as the romantic poet Shelly says in A Defense of Poetry; then do these moments automatically exclude everything political and social for every poet? In 19th century American verse, one finds a poet as solitary as Emily Dickinson, and of course a poet as socially gregarious Walt Whitman. While these

poets have different emphasis, both poets span the spectrum of the personal, social, and political. The most accurate portraits of human life always will touch on the social and the political, because people live in social and political milieus. In the reverse sense, looking at a mid-20th century political poem like Allen Ginsberg’s “America,” Ginsberg decries the war and poverty of the 1950s, which remain timely in the first decade of the 21st century, despite their “timeliness.” Ginsberg’s poem asks in modern language, “Am I my brother’s keeper” when he says in the opening lines, “When will we end the human war?” At the same time, the poem is a personal portrait of a man harried by the social milieu he cannot accept.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by Greg Mosson

The Potomac

Why should poets address political issues, ask some critics with arched disapproving eyebrows, and then often they answer that politics its too timely a subject for quality poetry. Question and the answer miss the point. First of all, any subject matter is timely in poetry. Robert Frost’s classic second book North of Boston is almost entirely comprised of narrative dialogues of people right in the middle of things, and yet the poetry he crafted with it will remain relevant as long as the English language does. The poet in the classic sense always faces the technical difficulty of making life at hand relevant to the teeming generations. The question is much more interesting if reversed: Why should poets exclude political and social issues from their poetry?

If poetry is “a statement in words about an experience,” to use critic Yvors Winters’ definition in The Function of Criticism; then why should the political aspects of “experience” be excluded from poetry? Helen Vendler in her book Poets Thinking sees “poets as people who are always thinking, who create texts that embody elaborate and finely precise (and essentially unending) meditation.” While 20th century history shows many examples of totalitarian governments oppressing artists who dare to address state matters in their work, why should poets on their own narrow their thinking to the nooks and crannies of just personal space (as if personal space can be so cut off from other people and the social and natural worlds). Lastly, if poetry is “the record of the best and happiest moments of the happiest and best minds,” as the romantic poet Shelly says in A Defense of Poetry; then do these moments automatically exclude everything political and social for every poet? In 19th century American verse, one finds a poet as solitary as Emily Dickinson, and of course a poet as socially gregarious Walt Whitman. While these

poets have different emphasis, both poets span the spectrum of the personal, social, and political. The most accurate portraits of human life always will touch on the social and the political, because people live in social and political milieus. In the reverse sense, looking at a mid-20th century political poem like Allen Ginsberg’s “America,” Ginsberg decries the war and poverty of the 1950s, which remain timely in the first decade of the 21st century, despite their “timeliness.” Ginsberg’s poem asks in modern language, “Am I my brother’s keeper” when he says in the opening lines, “When will we end the human war?” At the same time, the poem is a personal portrait of a man harried by the social milieu he cannot accept.

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Al Jazeera: Superclass

Superclass

Al Jazeera

A new breed has emerged; they set the global agenda, ride on Gulfstreams and manage the credit crunch in their spare time.

They are anything but elected; they are entrepreneurs and entertainers, media moguls and former politicians - the self-made super rich who are using their money to lay down a new set of global rules.

They have more in common with each other than with their countrymen, set apart by their ability to regularly influence the lives of millions of people around the globe.

So where did this new global aristocracy come from and who is keeping them in check?

Why should Oprah Winfrey have the ear of President Obama, and who gave Shakira the right to dictate education policy?

But then again, when you have as much money as Bill Gates and you are prepared to give it over to a good cause who is going to stop you?

It is all well and good until the revolving door spins in the wrong direction. Empire talks to Christopher Hitchens about Henry Kissinger and his life beyond elected power - it does not seem to have changed that much.

Is the world suffering from a global governance gap? Should we be worried that the superclass seems to have an ever-expanding reach that bypasses governments and remains unchecked?

Link to the Webpage

Al Jazeera

A new breed has emerged; they set the global agenda, ride on Gulfstreams and manage the credit crunch in their spare time.

They are anything but elected; they are entrepreneurs and entertainers, media moguls and former politicians - the self-made super rich who are using their money to lay down a new set of global rules.

They have more in common with each other than with their countrymen, set apart by their ability to regularly influence the lives of millions of people around the globe.

So where did this new global aristocracy come from and who is keeping them in check?

Why should Oprah Winfrey have the ear of President Obama, and who gave Shakira the right to dictate education policy?

But then again, when you have as much money as Bill Gates and you are prepared to give it over to a good cause who is going to stop you?

It is all well and good until the revolving door spins in the wrong direction. Empire talks to Christopher Hitchens about Henry Kissinger and his life beyond elected power - it does not seem to have changed that much.

Is the world suffering from a global governance gap? Should we be worried that the superclass seems to have an ever-expanding reach that bypasses governments and remains unchecked?

Link to the Webpage

Labels:

Celebrity,

Christopher Hitchens,

Class,

David Rothkopf,

Elites,

Globalization,

Janine Wedel,

Jeff Faux,

Ken Silverstein,

Mathhew Bishop,

Media,

Moises Naim,

Paul Farhi,

Paul Theroux,

Philanthropy

Robin Murray and Joe Heumann: Passage as journey in Sherman Alexie’s Smoke Signals -- a narrative of environmental adaptation

Passage as journey in Sherman Alexie’s Smoke Signals: a narrative of environmental adaptation

by Robin Murray and Joe Heumann

Jump Cut

...

Much has been written about Native Americans’ removal to reservation lands. After more than a century of skirmishes with tribes from New England to Florida, Andrew Jackson encouraged Congress to pass the 1830 Indian Removal Act, claiming it would separate Native Americans from the onslaught of settlers moving ever westward and help them evolve into what he saw as a civilized community. In 1832, Jackson insisted that Native Americans be removed from prime farming land in the Southeast and moved to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma on what has become known as the Trail of Tears. Of the 15,000 Cherokees who began the journey, 4000 died, and many more of the 70,000 moved to Indian Territory also died along the way. The move opened up the reservation system, however, and after battles with whites in the 1860s and 70s, Plains Indian tribes were also forcibly moved to reservations, this time in Oklahoma, Arizona, Utah, and other less productive and arable lands in the West.

From the beginning of the reservation system, life on “the Rez” was like hell on earth. On these reservations, Indian agents attempted to force Native Americans to farm infertile lands, leaving them close to starvation since their allotment of cattle was small and sometimes stolen by corrupt government officials. According to Gary D. Sandefur,

Native Americans on reservations were isolated “in places with few natural resources, far from contact with the developing U.S. economy and society” (37). Breaking up reservation land into allotments after the 1887 Dawes Act only had a negative effect since the land provided was unfit for farming or ranching, and the remaining land was purchased at low prices or stolen for white settlers to homestead.

Reservation life for the Coeur d’Alene, Sherman Alexie’s tribe, has an equally brutal history, but, as Alexie asserts, “No one winds up on the Spokane Indian Reservation by accident” (quoted in Cornwall). The Coeur d’Alene tribe of the Upper and Middle Spokanes were late to the reservation system, entering an agreement with the United States in 1887 after the Dawes Act was signed. This tribe entered into a treaty more than six years after the Lower Spokanes had moved onto the Spokane Indian Reservation, resisting the move to reservation land in Lower Spokane County primarily because it was less desirable for hunting and fishing than the middle and upper Spokane. To maintain their claim on aboriginal lands, they moved onto the Coeur d’Alene Reservation in Idaho and other reservations, including the Spokane, receiving monetary compensation for houses, cattle, seeds, and farm implements. By 1905, however, the reservations lost rights to water in the Spokane River to the Little Falls Power Plant, and by 1909, the Spokane Reservation was opened up for homesteading. Coeur d’ Alene and other tribes on the reservation were now limited to allotments of from eighty to 160 acres on land too rocky for farming.

A year later, minerals were found on reservations in Idaho. But this seemingly beneficial discovery has had catastrophic environmental results. Traditional tribal fishing became impossible. According to the Official Site of the Coeur d’ Alene Tribe,

“Over a 100 year period, the mining industry in Idaho’s Silver Valley dumped 72 million tons of mine waste into the Coeur d’Alene watershed. As mining and smelting operations grew, they produced billions of dollars in silver, lead, and zinc. In the process, natural life in the Coeur d’Alene River was wiped out.”

The Spokane Reservation suffered even worse repercussions from mining waste. In 1954, at the height of the Cold War, Jim and John LeBret, both tribal members, found uranium on the side of Spokane Reservation, and the Newmont Mining Company bought the rights to the Sherwood, Dawn, and Midnight Mines, all on reservation lands. The Midnight Mine remained active for twenty-seven years and became “an economic and social mainstay of the reservation,” but it also had devastating environmental consequences (Cornwall). According to Cornwall, Sherman Alexie “felt threatened by the uranium mines near his home on the Spokane Indian Reservation” after his grandmother died from esophageal cancer in 1980 and asserted, “I have very little doubt that I’m going to get cancer” (quoted in Cornwall).

To Read the Rest of the Essay

by Robin Murray and Joe Heumann

Jump Cut

...

Much has been written about Native Americans’ removal to reservation lands. After more than a century of skirmishes with tribes from New England to Florida, Andrew Jackson encouraged Congress to pass the 1830 Indian Removal Act, claiming it would separate Native Americans from the onslaught of settlers moving ever westward and help them evolve into what he saw as a civilized community. In 1832, Jackson insisted that Native Americans be removed from prime farming land in the Southeast and moved to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma on what has become known as the Trail of Tears. Of the 15,000 Cherokees who began the journey, 4000 died, and many more of the 70,000 moved to Indian Territory also died along the way. The move opened up the reservation system, however, and after battles with whites in the 1860s and 70s, Plains Indian tribes were also forcibly moved to reservations, this time in Oklahoma, Arizona, Utah, and other less productive and arable lands in the West.

From the beginning of the reservation system, life on “the Rez” was like hell on earth. On these reservations, Indian agents attempted to force Native Americans to farm infertile lands, leaving them close to starvation since their allotment of cattle was small and sometimes stolen by corrupt government officials. According to Gary D. Sandefur,

“The lands reserved for Indian use were generally regarded as the least desirable by whites and were almost always located for from major population centers, trails, and transportation routes that later became part of the modern system of metropolitan areas, highways and railroads” (37).

Native Americans on reservations were isolated “in places with few natural resources, far from contact with the developing U.S. economy and society” (37). Breaking up reservation land into allotments after the 1887 Dawes Act only had a negative effect since the land provided was unfit for farming or ranching, and the remaining land was purchased at low prices or stolen for white settlers to homestead.

Reservation life for the Coeur d’Alene, Sherman Alexie’s tribe, has an equally brutal history, but, as Alexie asserts, “No one winds up on the Spokane Indian Reservation by accident” (quoted in Cornwall). The Coeur d’Alene tribe of the Upper and Middle Spokanes were late to the reservation system, entering an agreement with the United States in 1887 after the Dawes Act was signed. This tribe entered into a treaty more than six years after the Lower Spokanes had moved onto the Spokane Indian Reservation, resisting the move to reservation land in Lower Spokane County primarily because it was less desirable for hunting and fishing than the middle and upper Spokane. To maintain their claim on aboriginal lands, they moved onto the Coeur d’Alene Reservation in Idaho and other reservations, including the Spokane, receiving monetary compensation for houses, cattle, seeds, and farm implements. By 1905, however, the reservations lost rights to water in the Spokane River to the Little Falls Power Plant, and by 1909, the Spokane Reservation was opened up for homesteading. Coeur d’ Alene and other tribes on the reservation were now limited to allotments of from eighty to 160 acres on land too rocky for farming.

A year later, minerals were found on reservations in Idaho. But this seemingly beneficial discovery has had catastrophic environmental results. Traditional tribal fishing became impossible. According to the Official Site of the Coeur d’ Alene Tribe,

“Over a 100 year period, the mining industry in Idaho’s Silver Valley dumped 72 million tons of mine waste into the Coeur d’Alene watershed. As mining and smelting operations grew, they produced billions of dollars in silver, lead, and zinc. In the process, natural life in the Coeur d’Alene River was wiped out.”

The Spokane Reservation suffered even worse repercussions from mining waste. In 1954, at the height of the Cold War, Jim and John LeBret, both tribal members, found uranium on the side of Spokane Reservation, and the Newmont Mining Company bought the rights to the Sherwood, Dawn, and Midnight Mines, all on reservation lands. The Midnight Mine remained active for twenty-seven years and became “an economic and social mainstay of the reservation,” but it also had devastating environmental consequences (Cornwall). According to Cornwall, Sherman Alexie “felt threatened by the uranium mines near his home on the Spokane Indian Reservation” after his grandmother died from esophageal cancer in 1980 and asserted, “I have very little doubt that I’m going to get cancer” (quoted in Cornwall).

To Read the Rest of the Essay

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Allison Kilkenney: TIME magazine uses exploitive photo to pimp nation-building

TIME magazine uses exploitive photo to pimp nation-building

without comments

by Allison Kilkenney

Unreported

This morning, TIME Managing Editor Richard Stengel was one of the guests on Morning Joe because he drops by every week to unveil the new cover of TIME so my grandmother will know what it looks like when she decides not to buy it at the drugstore.

This latest edition’s cover is of a young Afghan woman who has had her nose and ears cut off by the Taliban. Stengel used the terribly sad image to argue that the US must stay in Afghanistan forever because, if we leave, women will become the victims of retribution.

Stengel also took issue with Biden’s assertion that we are not in the business of nation-building. Actually, says the guy with zero nation-building experience (playing on the Princeton basketball team – Go Tigers! – doesn’t count,) we are in the business of nation-building, and if you take issue with that reality, look at this poor girl – LOOK AT HER.

To my great surprise, Mike Barnacle sprang to life long enough to ask Stengel if the U.S. should permanently occupy every country that possesses a suffering population. What about Cambodia and Vietnam? What about Africa? In Congo, around 5.4 million people died in a single decade. Don’t they deserve Stengel’s sympathy? Furthermore, what about China and Saudi Arabia – two countries famous for their worker exploitation and human rights violations? Stengel dismissed those concerns, making the argument that we’re in the Middle East right now, so we should stay forever until all suffering has been alleviated with the healing power of our guns and bombs.

What is particularly aggravating about this latest TIME cover is that this is one of the only times a mainstream media outlet has lifted its self-inflicted censorship to show a victim of Afghan violence in a prominent way. Unfortunately, the editors at TIME didn’t show the world any of the horrific images of civilians who have become casualties of the U.S.-led invasion and occupation of the region, or any photos capturing the tens of thousands of innocent men, women, and children who have died during the Afghanistan occupation. Instead, Stengel and TIME decided to slap this poor girl on the cover as a way to pimp their nation-building bias, which by the way, nonpartisan Very Serious mainstream media publications aren’t supposed to have. Stengel was peddling an agenda like a lowly blogger.

Undoubtedly, there are those in the Taliban who seek to abuse and hurt women. That behavior is evil and should be condemned. The U.S. should seek to provide amnesty to endangered women wherever they live. However, obliterating the woman’s village in the spirit of “helping” to “liberate” her doesn’t make much sense. This latter scenario is what is happening far more often in Afghanistan.

To Read the Rest of the Commentary

without comments

by Allison Kilkenney

Unreported

This morning, TIME Managing Editor Richard Stengel was one of the guests on Morning Joe because he drops by every week to unveil the new cover of TIME so my grandmother will know what it looks like when she decides not to buy it at the drugstore.

This latest edition’s cover is of a young Afghan woman who has had her nose and ears cut off by the Taliban. Stengel used the terribly sad image to argue that the US must stay in Afghanistan forever because, if we leave, women will become the victims of retribution.

Stengel also took issue with Biden’s assertion that we are not in the business of nation-building. Actually, says the guy with zero nation-building experience (playing on the Princeton basketball team – Go Tigers! – doesn’t count,) we are in the business of nation-building, and if you take issue with that reality, look at this poor girl – LOOK AT HER.

To my great surprise, Mike Barnacle sprang to life long enough to ask Stengel if the U.S. should permanently occupy every country that possesses a suffering population. What about Cambodia and Vietnam? What about Africa? In Congo, around 5.4 million people died in a single decade. Don’t they deserve Stengel’s sympathy? Furthermore, what about China and Saudi Arabia – two countries famous for their worker exploitation and human rights violations? Stengel dismissed those concerns, making the argument that we’re in the Middle East right now, so we should stay forever until all suffering has been alleviated with the healing power of our guns and bombs.

What is particularly aggravating about this latest TIME cover is that this is one of the only times a mainstream media outlet has lifted its self-inflicted censorship to show a victim of Afghan violence in a prominent way. Unfortunately, the editors at TIME didn’t show the world any of the horrific images of civilians who have become casualties of the U.S.-led invasion and occupation of the region, or any photos capturing the tens of thousands of innocent men, women, and children who have died during the Afghanistan occupation. Instead, Stengel and TIME decided to slap this poor girl on the cover as a way to pimp their nation-building bias, which by the way, nonpartisan Very Serious mainstream media publications aren’t supposed to have. Stengel was peddling an agenda like a lowly blogger.

Undoubtedly, there are those in the Taliban who seek to abuse and hurt women. That behavior is evil and should be condemned. The U.S. should seek to provide amnesty to endangered women wherever they live. However, obliterating the woman’s village in the spirit of “helping” to “liberate” her doesn’t make much sense. This latter scenario is what is happening far more often in Afghanistan.

To Read the Rest of the Commentary

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Glenn Greenwald: The WikiLeaks Afghanistan Leak

The WikiLeaks Afghanistan leak

Glenn Greenwald

Salon

The most consequential news item of the week will obviously be -- or at least should be -- the massive new leak by WikiLeaks of 90,000 pages of classified material chronicling the truth about the war in Afghanistan from 2004 through 2009. Those documents provide what The New York Times calls "an unvarnished, ground-level picture of the war in Afghanistan that is in many respects more grim than the official portrayal." The Guardian describes the documents as "a devastating portrait of the failing war in Afghanistan, revealing how coalition forces have killed hundreds of civilians in unreported incidents, Taliban attacks have soared and Nato commanders fear neighbouring Pakistan and Iran are fueling the insurgency."

In addition to those two newspapers, WikiLeaks also weeks ago provided these materials to Der Spiegel, on the condition that all three wait until today to write about them. These outlets were presumably chosen by WikiLeaks with the intent to ensure maximum exposure among the American and Western European citizenries which continue to pay for this war and whose governments have been less than forthcoming about what is taking place [a CIA document prepared in March, 2010 -- and previously leaked by WikiLeaks -- plotted how to prevent public opinion in Western Europe from turning further against the war and thus forcing their Governments to withdraw; the CIA's conclusion: the most valuable asset in putting a pretty face on the war for Western Europeans is Barack Obama's popularity with those populations].

The White House has swiftly vowed to continue the war and predictably condemned WikiLeaks rather harshly. It will be most interesting to see how many Democrats -- who claim to find Daniel Ellsberg heroic and the Pentagon Papers leak to be unambiguously justified -- follow the White House's lead in that regard. Ellsberg's leak -- though primarily exposing the amoral duplicity of a Democratic administration -- occurred when there was a Republican in the White House. This latest leak, by contrast, indicts a war which a Democratic President has embraced as his own, and documents similar manipulation of public opinion and suppression of the truth well into 2009. It's not difficult to foresee, as Atrios predicted, that media "coverage of [the] latest [leak] will be about whether or not it should have been published," rather than about what these documents reveal about the war effort and the government and military leaders prosecuting it. What position Democratic officials and administration supporters take in the inevitable debate over WikiLeaks remains to be seen (by shrewdly leaking these materials to 3 major newspapers, which themselves then published many of the most incriminating documents, WikiLeaks provided itself with some cover).

Note how obviously lame is the White House's prime tactic thus far for dismissing the importance of the leak: that the documents only go through December, 2009, the month when Obama ordered his "surge," as though that timeline leaves these documents without any current relevance. The Pentagon Papers only went up through 1968 and were not released until 3 years later (in 1971), yet having the public behold the dishonesty about the war had a significant effect on public opinion, as well as the willingness of Americans to trust future government pronouncements. At the very least, it's difficult to imagine this leak not having the same effect. Then again, since -- unlike Vietnam -- only a tiny portion of war supporters actually bears any direct burden from the war (themselves or close family members fighting it), it's possible that the public will remain largely apathetic even knowing what they will now know. It's relatively easy to support and/or acquiesce to a war when neither you nor your loved ones are risking their lives to fight it.

To Read the Entire Column, Acess Hyperlinked Resources and Further Updates

More resources:

Jay Rosen: The Afghanistan War Logs Released by Wikileaks, the World's First Stateless News Organization

Glenn Greenwald

Salon

The most consequential news item of the week will obviously be -- or at least should be -- the massive new leak by WikiLeaks of 90,000 pages of classified material chronicling the truth about the war in Afghanistan from 2004 through 2009. Those documents provide what The New York Times calls "an unvarnished, ground-level picture of the war in Afghanistan that is in many respects more grim than the official portrayal." The Guardian describes the documents as "a devastating portrait of the failing war in Afghanistan, revealing how coalition forces have killed hundreds of civilians in unreported incidents, Taliban attacks have soared and Nato commanders fear neighbouring Pakistan and Iran are fueling the insurgency."

In addition to those two newspapers, WikiLeaks also weeks ago provided these materials to Der Spiegel, on the condition that all three wait until today to write about them. These outlets were presumably chosen by WikiLeaks with the intent to ensure maximum exposure among the American and Western European citizenries which continue to pay for this war and whose governments have been less than forthcoming about what is taking place [a CIA document prepared in March, 2010 -- and previously leaked by WikiLeaks -- plotted how to prevent public opinion in Western Europe from turning further against the war and thus forcing their Governments to withdraw; the CIA's conclusion: the most valuable asset in putting a pretty face on the war for Western Europeans is Barack Obama's popularity with those populations].

The White House has swiftly vowed to continue the war and predictably condemned WikiLeaks rather harshly. It will be most interesting to see how many Democrats -- who claim to find Daniel Ellsberg heroic and the Pentagon Papers leak to be unambiguously justified -- follow the White House's lead in that regard. Ellsberg's leak -- though primarily exposing the amoral duplicity of a Democratic administration -- occurred when there was a Republican in the White House. This latest leak, by contrast, indicts a war which a Democratic President has embraced as his own, and documents similar manipulation of public opinion and suppression of the truth well into 2009. It's not difficult to foresee, as Atrios predicted, that media "coverage of [the] latest [leak] will be about whether or not it should have been published," rather than about what these documents reveal about the war effort and the government and military leaders prosecuting it. What position Democratic officials and administration supporters take in the inevitable debate over WikiLeaks remains to be seen (by shrewdly leaking these materials to 3 major newspapers, which themselves then published many of the most incriminating documents, WikiLeaks provided itself with some cover).

Note how obviously lame is the White House's prime tactic thus far for dismissing the importance of the leak: that the documents only go through December, 2009, the month when Obama ordered his "surge," as though that timeline leaves these documents without any current relevance. The Pentagon Papers only went up through 1968 and were not released until 3 years later (in 1971), yet having the public behold the dishonesty about the war had a significant effect on public opinion, as well as the willingness of Americans to trust future government pronouncements. At the very least, it's difficult to imagine this leak not having the same effect. Then again, since -- unlike Vietnam -- only a tiny portion of war supporters actually bears any direct burden from the war (themselves or close family members fighting it), it's possible that the public will remain largely apathetic even knowing what they will now know. It's relatively easy to support and/or acquiesce to a war when neither you nor your loved ones are risking their lives to fight it.

To Read the Entire Column, Acess Hyperlinked Resources and Further Updates

More resources:

Jay Rosen: The Afghanistan War Logs Released by Wikileaks, the World's First Stateless News Organization

Behind the News with Doug Henwood: Norman Finkelstein on Israel's Invasion of Gaza in 2009

Norman Finkelstein

Behind the News with Doug Henwood

Norman Finkelstein, author of This Time We Went Too Far, talks about Israel’s invasion of Gaza in late 2009, and about changing U.S. public opinion towards that country

To Listen to the Interview

Behind the News with Doug Henwood

Norman Finkelstein, author of This Time We Went Too Far, talks about Israel’s invasion of Gaza in late 2009, and about changing U.S. public opinion towards that country

To Listen to the Interview

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

John Pilger: There Is a War on Journalism

John Pilger: There Is a War on Journalism

Democracy Now

It’s been a week since Rolling Stone published its article on General Stanley McChrystal that eventually led to him being fired by President Obama. Since the article came out, Rolling Stone and the reporter who broke the story, Michael Hastings, have come under attack in the mainstream media for violating the so-called "ground rules" of journalism. But the investigative journalist and documentary filmmaker John Pilger says Hastings was simply doing what all true journalists need to do.

To Watch/Listen/Read

Democracy Now

It’s been a week since Rolling Stone published its article on General Stanley McChrystal that eventually led to him being fired by President Obama. Since the article came out, Rolling Stone and the reporter who broke the story, Michael Hastings, have come under attack in the mainstream media for violating the so-called "ground rules" of journalism. But the investigative journalist and documentary filmmaker John Pilger says Hastings was simply doing what all true journalists need to do.

To Watch/Listen/Read

Democracy Now: Jury Convicts Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge of Lying About Torture

Jury Convicts Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge of Lying About Torture

Democracy Now

Decades after torture allegations were first leveled against former Chicago police commander Jon Burge, a federal jury has found him guilty of lying about torturing prisoners into making confessions. Burge has long been accused of overseeing the systematic torture of more than 100 African American men. Two years ago federal prosecutors finally brought charges against Burge—not for torture, but for lying about it. On Monday afternoon, after a five-week trial, Jon Burge was found guilty on all counts of perjury and obstruction of justice for lying about the abuse. He could face up to forty-five years in prison.

To Watch/Listen/Read

Democracy Now

Decades after torture allegations were first leveled against former Chicago police commander Jon Burge, a federal jury has found him guilty of lying about torturing prisoners into making confessions. Burge has long been accused of overseeing the systematic torture of more than 100 African American men. Two years ago federal prosecutors finally brought charges against Burge—not for torture, but for lying about it. On Monday afternoon, after a five-week trial, Jon Burge was found guilty on all counts of perjury and obstruction of justice for lying about the abuse. He could face up to forty-five years in prison.

To Watch/Listen/Read

Gabriel Gatehouse: US Military 'Fails to Account' for Iraq Reconstruction Billions

US 'Fails to Account' for Iraq Reconstruction Billions

by Gabriel Gatehouse

BBC; Reprinted in Common Dreams

A US federal watchdog has criticized the US military for failing to account properly for billions of dollars it received to help rebuild Iraq.

The Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction says the US Department of Defense is unable to account properly for 96% of the money.

Billions have gone to rebuild Iraq but much of the money is impossible to trace, says a US audit. Out of just over $9bn (£5.8bn), $8.7bn is unaccounted for, the inspector says.

The US military said the funds were not necessarily missing, but that spending records might have been archived.

In a response attached to the report, it said attempting to account for the money might require "significant archival retrieval efforts".

Much of the money came from the sale of Iraqi oil and gas.

Some frozen Saddam Hussein-era assets were also sold off.

The funds in question were administered by the US Department of Defense between 2004 and 2007, and were earmarked for reconstruction projects.

But, the report says, a lack of proper accounting makes it impossible to say exactly what happened to most of the money.

This is not the first time that allegations of missing billions have surfaced in relation to the US-led invasion of Iraq and its aftermath.

To Read the Rest of the Report

by Gabriel Gatehouse

BBC; Reprinted in Common Dreams

A US federal watchdog has criticized the US military for failing to account properly for billions of dollars it received to help rebuild Iraq.

The Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction says the US Department of Defense is unable to account properly for 96% of the money.

Billions have gone to rebuild Iraq but much of the money is impossible to trace, says a US audit. Out of just over $9bn (£5.8bn), $8.7bn is unaccounted for, the inspector says.

The US military said the funds were not necessarily missing, but that spending records might have been archived.

In a response attached to the report, it said attempting to account for the money might require "significant archival retrieval efforts".

Much of the money came from the sale of Iraqi oil and gas.

Some frozen Saddam Hussein-era assets were also sold off.

The funds in question were administered by the US Department of Defense between 2004 and 2007, and were earmarked for reconstruction projects.

But, the report says, a lack of proper accounting makes it impossible to say exactly what happened to most of the money.

This is not the first time that allegations of missing billions have surfaced in relation to the US-led invasion of Iraq and its aftermath.

To Read the Rest of the Report

Ian Buchanan: Bernardo Bertolucci's The Dreamers; Kristin Ross' May 68 & Its Afterlives; Deleuze & Guattari's Anti-Oedipus

(If you would like a broad note form introduction to D & G's Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia check out my attempt of carving out meaning from this difficult, but powerful theoretical text.)

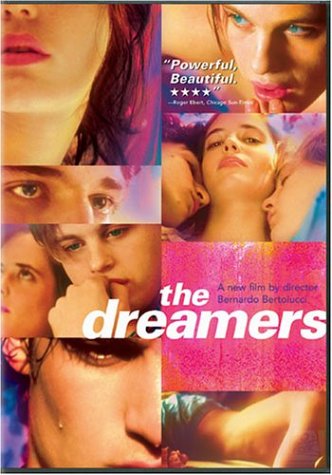

Bernardo Bertolucci's highly stylized film about May '68, The Dreamers (2003), is a vivid illustration of the narrow, exclusively Parisian image of the events that has to be overturned if we are to see things in their proper historical light. Bertolucci depicts May '68 as a student protest, which is how it began, but its significance to history derives from the fact that it soon became a nationwide protest involving more than 9 million striking workers. The effects of the strikes are made apparent to us in the film in the form of mounds of uncollected garbage mouldering in stairwells and on street corners, but the striking workers themselves are never shown. Moreover, Bertolucci makes it seem the student protests began in the privileged cloisters of the Latin Quarter, and not, as was actually the case, in the functionalist towers of the new universities in the outlying immigrant slum areas of Nanterre and Vincennes, where students were provided 'with a direct "lived" lesson in uneven development.' According to the great Marxist philosopher Henri Lefebvre, it was this daily 'experience' of the callousness of the state that radicalized the students and provided the catalyst for their connection to workers' movements. Secondly, through the vehicle of its twin brother and sister protagonists Isabelle (Eva Green) and Theo (Louis Garrel), both in their late teens or early twenties and still living at home with their relatively well-to-do parents, it depicts the students who took part in May '68 as naive, self-absorbed and perverted. Cocooned in their own fantasy world concocted from fragments of movies and books, Isabelle and Theo are a postmodern version of Ulrich and Agathe. They meet an American exchange student, Matthew (Michael Pitt), and invite him to join them. When their parents go away, they are able to indulge their whims uninhibitedly and the scene is set for a cliched romp through the three staples of 1960s counterculture, namely, sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll. They take bubble baths together and get stoned on hash; Matthew and Isabelle make love on the kitchen floor while Theo fries an egg and looks on with Brechtian disinterest; they drink papa's fine wine straight from the bottle and debate movies and politics long into the night as though nothing else mattered. They ignore the world outside.

Mathhew soon upsets their idyllic universe by accusing them both of being unwordly: Isabelle because she's never been out on a real 'date' and Theo because of his starry-eyed romanticization of the Chinese Red Guards. It all begins when Isabelle demands that he shave his pubic hair as a sign of love. He refuses because the demand is in his view nothing but a silly game, an infantilizing gesture that proves their disconnection from the reality of what is going on around them. He tells them both 'there's something going on out there, I can feel it,' but neither Isabelle nor Theo seem to care. Their political awakening comes soon enough though in the form of a brick thrown through their apartment window. The brick literally shatters their world, but also save their lives too. Awakening after another of their orgiastic episodes, Isabelle finds a cheque written by her parents and realizes they must have been in the apartment and therefore witnessed their dishabille state and perhaps guessed at their decadent behavior -- the three of them are naked, sleeping side by side in a tent Isabelle erected in the living room. Mortally ashamed, Isabelle decides to kill herself and Theo and Matthew as well, so she switches on the gas and lays down between the two boys and readies herself for death. It is at this point that the window is broken. The intrusion of the street into their self-enclosed fantasy world is thus presented as a life-saving event. The brick breaks the spell of self-indulgence they've all been under and suddenly both Isabelle and Theo realize something is going on outside and that it does concern them, does interest them, and is more important than their fantasy world. The three of them rush first to the balcony to witness the events below and then to the street to join in. But here the happy trio split up because only Isabelle and Theo are willing to take part. Mathhew, a self-proclaimed pacifist, turns his back on them. Matthew recoils in horror when he sees Theo with a Molotov cocktail in his hands and refuses to join them when they rush hand in hand towards the fray. Bertolucci's last act then is to make May '68 an exclusively French affair, but also wrongheaded and needlessly violent.

Kristin Ross's account of May '68 takes us in precisely the opposite direction to Bertolucci. She is anxious that we see that May '68 was not just a student protest, and that those involved were anything but naive (in the sense of being unaware of history) and perhaps most importantly that it was part of a longer chain of events that stretched far beyond Paris. To begin with, Ross argues for an enlargement of the timeframe in which the events are considered, not just beyond the month of May itself, which as she shows (and Bertolucci's film exemplifies) restricts the events to a limited series of goings-on at the Sorbonne, but back two decades to the start of the Algerian War. This, in turn, enables her to argue that May '68 was not a great cultural reform, a push toward modernisation, or the dawning sun of a new individualism. It was above all not a revolt on the part of the sociological category "youth". It was rather the revolt of a broad cross-section of workers and students of all ages who had grown up with and witnessed the sickening brutality of the Gaullist regime's failed attempt to deny Algeria its independence. 'Algeria defined a fracture in French society, in its identity, by creating a break between the official "humanist" discourse of that society and French practices occurring in Algeria and occasionally within France as well.' It was impossible to reconcile the ideal of a benevolent welfare state espoused by France's leaders with the truncheon-wielding reality of the hegemonic state, except perhaps in oedipal terms by casting President de Gaulle in the role of the father and relegating the protesters to the rank of children. Anti-Oedipus is of course directed against this pseudo-psychoanalytic account of the events and indeed Deleuze and Guattari argue that it was precisely the example of Algeria that makes it clear that politics cannot be reduced to an oedipal struggle. 'It is strange', they write, 'that we had to wait for the dreams of the colonised peoples in order to see that, on the vertices of the pseudo triangle, mommy was dancing with the missionary, daddy was being fucked by the tax collector, while the self was being beaten by the white man.' (AO, 105-9/114)

What Fanon's work showed us, Deleuze and Guattari go on to suggest, is that every subject is directly coupled to elements of their:

As Belden Fields writes, the Algerian War was crucial stimulus for the radicalization of French students in the 1960s because it delegitimized the structures of the state. 'The educational system, for instance, came to be viewed as a conduit funneling young people into military bureaucracies, whether public or private, to earn a living as a supporting cog in a system of repressive privilege'. Jean-Paul Belmondo, 'the doomed anti-hero' of Jean-Luc Goddard's path-breaking film of 1960, A bout de souffle [Breathless], is usually taken as the 'screen representative of that young generation of Frenchmen condemned to serve, suffer, and even die in Algeria'. This perceived lack of control over their own destiny, even among the relatively privileged classes to which the majority of students actually belonged, coupled with the oppressive archaism of the educational system itself, and indeed the state structure as a whole, generated among radicalized youth a powerful sense of empathy with all victims of the state. The students saw themselves as being in solidarity with factory workers, despite the fact that their destiny was to be the managers who would one day have to 'manage' these selfsame workers. In other words, in spite of the fact that their class interests were different, the students and the workers were nonetheless able to find a point of common interest in their dispute with the state. The usual divide and conquer tactics the state relies on to stratify the population and ensure that precisely this type of connection between strata doesn't occur failed spectacularly. It failed because the state was unable, at least in the first instance, to present itself as something other than a huge, oppressive monolithic edifice determined to stamp out dissent with an iron fist. Unfortunately, the French Communist Party, still a very strong and widely supported institution, was tarnished by its 'pragmatic response to the war -- the party line, that the war should be ended by negotiated settlement, was strictly enforced, with the result that it too came to be seen as ossified and antiquated and of little relevance to the needs of the present generation. Deleuze and Guattari clearly shared this view; their frequent anti-reformist remarks should be seen as directed at the French Communist Party.

Ross's second move is to argue for an enlargement of the geographical framework in which the events are considered, not just beyond the Latin Quarter to the outer suburbs of Paris, but beyond France altogether to still another of its former colonies, namely Vietnam, which having rid itself of its French masters in the 1950s was then in the process of expelling the American pretenders:

In fact, the events themselves were sparked by an incident -- a window of the American Express building on rue Scribe in Paris was broken -- that occurred as part of a student protest against the war in Veitnam on 20 March 1968. The irruption of student protest at Nanterre two days later was in part provoked by the heavy-handedness of the police response to the anti-Vietnam march. The students at Nantarre rallied themselves under the banner of 'Mouvement du 22 mars', deliberately recalling Castro's 'July 26th Movement' commemorating the attack on Moncada fortress and start of the insurrection against Batista. 'Vietnam thus both launched the action in the streets as well as brought under one umbrella a number of groups ... as well as previously unaffiliated militants working together. For the protesters, students and workers alike, Vietnam made manifest processes that were thought to be merely latent in the West. For one thing, it revealed both the inherent violence of the postmodern capitalist state and the lengths to which it is prepared to go in order to preserve its power. It demonstrated a willingness on the part of the powerful to use violence against the powerless to defend the status quo. Vietnam also revealed the vulnerability of the super state and its susceptibility to a 'revolution from below'. Sartre, for one, was convinced that the true origin of May '68 was Vietnam because the example of Vietnamese guerrillas winning a war against a vastly superior force, albeit at the cost of an enormous loss of life, extended the domain of the possible for Western intellectuals who otherwise thought of themselves as powerless in the face of the state.

More concretely, French workers whose livelihoods were threatened by a process we know today as globalization, the process whereby local markets are forcibly opened to global competitors, saw themselves as victims of American imperialism too. Deleuze and Guattari were keenly aware of the high cost the structural adjustments (to use the purposefully dry language of economists):

On this point, Ross argues that the geographical boundary of the events of May needs to be widened to encompass Italy because the political convulsions wrought by the first stages of globalization were in Europe nowhere felt more keenly. The striking Fiat workers' slogan 'Vietnam is in our factories!' made the connection to American imperialism explicit. This is, then, Ross's third move: she argues for a redefinition of the sociological frame in which the events are considered. May '68 would not have been the event it was if the protest action had been confined to either the students or the workers or even the farmers. It was the fact that these groups, as well as many others, found it possible and necessary to link up with each other that resulted in the extraordinary event we know as May '68. But, and this is Ross's main point, none of these groups -- students, workers, farmers, etc. -- can be treated as pre-existing, self-contained, homogeneous entities. As for the encounters between these heterogeneous groups, they obviously cannot be treated in the same way that one might regard the actions of states agreeing by treaty to work together for the sake of a common interest. Ross suggests that the process might better be described as 'cultural contamination' and argues that it 'was encounters with people different from themselves -- and not the glow of shared identity -- that allowed a dream of change to flourish'. Ross's purpose, however, is not to assert the primacy of the individual, or indeed the primacy of differences, two moves which as [Fredric] Jameson has shown in his various critiques of Anglo-American cultural studies lead inexorably to political paralysis. By repudiating both the collective and the same under the utterly misconceived banner of 'anti-totalization', cultural studies has for all practical intents and purposes divested itself of two of the most basic prerequisites for politics, namely the potential for a common action and the identification of a common aim. Well aware of the pitfalls of valorizing the individual at the expense of the collective, the different at the expense of the same, Ross argues for an approach to the sociological dimension of May '68 that is perfectly attuned to Deleuze and Guattari's work.

Buchanan, Ian. Deleuze and Guattari's Anti-Oedipus. NY: Continuum, 2008: 13-19.

Bernardo Bertolucci's highly stylized film about May '68, The Dreamers (2003), is a vivid illustration of the narrow, exclusively Parisian image of the events that has to be overturned if we are to see things in their proper historical light. Bertolucci depicts May '68 as a student protest, which is how it began, but its significance to history derives from the fact that it soon became a nationwide protest involving more than 9 million striking workers. The effects of the strikes are made apparent to us in the film in the form of mounds of uncollected garbage mouldering in stairwells and on street corners, but the striking workers themselves are never shown. Moreover, Bertolucci makes it seem the student protests began in the privileged cloisters of the Latin Quarter, and not, as was actually the case, in the functionalist towers of the new universities in the outlying immigrant slum areas of Nanterre and Vincennes, where students were provided 'with a direct "lived" lesson in uneven development.' According to the great Marxist philosopher Henri Lefebvre, it was this daily 'experience' of the callousness of the state that radicalized the students and provided the catalyst for their connection to workers' movements. Secondly, through the vehicle of its twin brother and sister protagonists Isabelle (Eva Green) and Theo (Louis Garrel), both in their late teens or early twenties and still living at home with their relatively well-to-do parents, it depicts the students who took part in May '68 as naive, self-absorbed and perverted. Cocooned in their own fantasy world concocted from fragments of movies and books, Isabelle and Theo are a postmodern version of Ulrich and Agathe. They meet an American exchange student, Matthew (Michael Pitt), and invite him to join them. When their parents go away, they are able to indulge their whims uninhibitedly and the scene is set for a cliched romp through the three staples of 1960s counterculture, namely, sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll. They take bubble baths together and get stoned on hash; Matthew and Isabelle make love on the kitchen floor while Theo fries an egg and looks on with Brechtian disinterest; they drink papa's fine wine straight from the bottle and debate movies and politics long into the night as though nothing else mattered. They ignore the world outside.

Mathhew soon upsets their idyllic universe by accusing them both of being unwordly: Isabelle because she's never been out on a real 'date' and Theo because of his starry-eyed romanticization of the Chinese Red Guards. It all begins when Isabelle demands that he shave his pubic hair as a sign of love. He refuses because the demand is in his view nothing but a silly game, an infantilizing gesture that proves their disconnection from the reality of what is going on around them. He tells them both 'there's something going on out there, I can feel it,' but neither Isabelle nor Theo seem to care. Their political awakening comes soon enough though in the form of a brick thrown through their apartment window. The brick literally shatters their world, but also save their lives too. Awakening after another of their orgiastic episodes, Isabelle finds a cheque written by her parents and realizes they must have been in the apartment and therefore witnessed their dishabille state and perhaps guessed at their decadent behavior -- the three of them are naked, sleeping side by side in a tent Isabelle erected in the living room. Mortally ashamed, Isabelle decides to kill herself and Theo and Matthew as well, so she switches on the gas and lays down between the two boys and readies herself for death. It is at this point that the window is broken. The intrusion of the street into their self-enclosed fantasy world is thus presented as a life-saving event. The brick breaks the spell of self-indulgence they've all been under and suddenly both Isabelle and Theo realize something is going on outside and that it does concern them, does interest them, and is more important than their fantasy world. The three of them rush first to the balcony to witness the events below and then to the street to join in. But here the happy trio split up because only Isabelle and Theo are willing to take part. Mathhew, a self-proclaimed pacifist, turns his back on them. Matthew recoils in horror when he sees Theo with a Molotov cocktail in his hands and refuses to join them when they rush hand in hand towards the fray. Bertolucci's last act then is to make May '68 an exclusively French affair, but also wrongheaded and needlessly violent.

Kristin Ross's account of May '68 takes us in precisely the opposite direction to Bertolucci. She is anxious that we see that May '68 was not just a student protest, and that those involved were anything but naive (in the sense of being unaware of history) and perhaps most importantly that it was part of a longer chain of events that stretched far beyond Paris. To begin with, Ross argues for an enlargement of the timeframe in which the events are considered, not just beyond the month of May itself, which as she shows (and Bertolucci's film exemplifies) restricts the events to a limited series of goings-on at the Sorbonne, but back two decades to the start of the Algerian War. This, in turn, enables her to argue that May '68 was not a great cultural reform, a push toward modernisation, or the dawning sun of a new individualism. It was above all not a revolt on the part of the sociological category "youth". It was rather the revolt of a broad cross-section of workers and students of all ages who had grown up with and witnessed the sickening brutality of the Gaullist regime's failed attempt to deny Algeria its independence. 'Algeria defined a fracture in French society, in its identity, by creating a break between the official "humanist" discourse of that society and French practices occurring in Algeria and occasionally within France as well.' It was impossible to reconcile the ideal of a benevolent welfare state espoused by France's leaders with the truncheon-wielding reality of the hegemonic state, except perhaps in oedipal terms by casting President de Gaulle in the role of the father and relegating the protesters to the rank of children. Anti-Oedipus is of course directed against this pseudo-psychoanalytic account of the events and indeed Deleuze and Guattari argue that it was precisely the example of Algeria that makes it clear that politics cannot be reduced to an oedipal struggle. 'It is strange', they write, 'that we had to wait for the dreams of the colonised peoples in order to see that, on the vertices of the pseudo triangle, mommy was dancing with the missionary, daddy was being fucked by the tax collector, while the self was being beaten by the white man.' (AO, 105-9/114)

What Fanon's work showed us, Deleuze and Guattari go on to suggest, is that every subject is directly coupled to elements of their:

historical situation -- the soldier, the cop, the occupier, the collaborator, the radical, the resister, the boss, the boss's wife -- who constantly break all triangulations, and who prevent the entire situation from falling back on the familial complex and becoming internalised in it. (AO, 107/116)

As Belden Fields writes, the Algerian War was crucial stimulus for the radicalization of French students in the 1960s because it delegitimized the structures of the state. 'The educational system, for instance, came to be viewed as a conduit funneling young people into military bureaucracies, whether public or private, to earn a living as a supporting cog in a system of repressive privilege'. Jean-Paul Belmondo, 'the doomed anti-hero' of Jean-Luc Goddard's path-breaking film of 1960, A bout de souffle [Breathless], is usually taken as the 'screen representative of that young generation of Frenchmen condemned to serve, suffer, and even die in Algeria'. This perceived lack of control over their own destiny, even among the relatively privileged classes to which the majority of students actually belonged, coupled with the oppressive archaism of the educational system itself, and indeed the state structure as a whole, generated among radicalized youth a powerful sense of empathy with all victims of the state. The students saw themselves as being in solidarity with factory workers, despite the fact that their destiny was to be the managers who would one day have to 'manage' these selfsame workers. In other words, in spite of the fact that their class interests were different, the students and the workers were nonetheless able to find a point of common interest in their dispute with the state. The usual divide and conquer tactics the state relies on to stratify the population and ensure that precisely this type of connection between strata doesn't occur failed spectacularly. It failed because the state was unable, at least in the first instance, to present itself as something other than a huge, oppressive monolithic edifice determined to stamp out dissent with an iron fist. Unfortunately, the French Communist Party, still a very strong and widely supported institution, was tarnished by its 'pragmatic response to the war -- the party line, that the war should be ended by negotiated settlement, was strictly enforced, with the result that it too came to be seen as ossified and antiquated and of little relevance to the needs of the present generation. Deleuze and Guattari clearly shared this view; their frequent anti-reformist remarks should be seen as directed at the French Communist Party.

Ross's second move is to argue for an enlargement of the geographical framework in which the events are considered, not just beyond the Latin Quarter to the outer suburbs of Paris, but beyond France altogether to still another of its former colonies, namely Vietnam, which having rid itself of its French masters in the 1950s was then in the process of expelling the American pretenders:

In its battle with the United States, with the worldwide political and cultural domination the United States had exerted since the end of World War II, Vietnam made possible a merging of the themes of anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism ...

In fact, the events themselves were sparked by an incident -- a window of the American Express building on rue Scribe in Paris was broken -- that occurred as part of a student protest against the war in Veitnam on 20 March 1968. The irruption of student protest at Nanterre two days later was in part provoked by the heavy-handedness of the police response to the anti-Vietnam march. The students at Nantarre rallied themselves under the banner of 'Mouvement du 22 mars', deliberately recalling Castro's 'July 26th Movement' commemorating the attack on Moncada fortress and start of the insurrection against Batista. 'Vietnam thus both launched the action in the streets as well as brought under one umbrella a number of groups ... as well as previously unaffiliated militants working together. For the protesters, students and workers alike, Vietnam made manifest processes that were thought to be merely latent in the West. For one thing, it revealed both the inherent violence of the postmodern capitalist state and the lengths to which it is prepared to go in order to preserve its power. It demonstrated a willingness on the part of the powerful to use violence against the powerless to defend the status quo. Vietnam also revealed the vulnerability of the super state and its susceptibility to a 'revolution from below'. Sartre, for one, was convinced that the true origin of May '68 was Vietnam because the example of Vietnamese guerrillas winning a war against a vastly superior force, albeit at the cost of an enormous loss of life, extended the domain of the possible for Western intellectuals who otherwise thought of themselves as powerless in the face of the state.

More concretely, French workers whose livelihoods were threatened by a process we know today as globalization, the process whereby local markets are forcibly opened to global competitors, saw themselves as victims of American imperialism too. Deleuze and Guattari were keenly aware of the high cost the structural adjustments (to use the purposefully dry language of economists):

If we look at today's [1972] situation, power necessarily has a global or total vision. What I mean is that every form of repression today [repression actuelles], and they are multiple, is easily totalised, systematised from the point of view of power: the racist repression against immigrants, the repression in factories, the repression in schools and teaching, and the repression of youth in general. We mustn't look for the unity of these forms of repression only in reaction to May '68, but more so in a concerted preparation and organisation concerning our immediate future. Capitalism in France is dropping its liberal, paternalistic mask of full employment; it desperately needs a 'reserve' of unemployed workers. It's from this vantage point that unity can be found in the forms of repression I already mentioned; the limitation of immigration, once it's understood we're leaving the hardest and lowest paying jobs to them; the repression in factories, because now it's all about once again giving the French a taste for hard work; the struggle against youth and the repression in schools and teaching, because police repression must be all the more active now that there is less need for young people on the job market. (DI, 210/294)

On this point, Ross argues that the geographical boundary of the events of May needs to be widened to encompass Italy because the political convulsions wrought by the first stages of globalization were in Europe nowhere felt more keenly. The striking Fiat workers' slogan 'Vietnam is in our factories!' made the connection to American imperialism explicit. This is, then, Ross's third move: she argues for a redefinition of the sociological frame in which the events are considered. May '68 would not have been the event it was if the protest action had been confined to either the students or the workers or even the farmers. It was the fact that these groups, as well as many others, found it possible and necessary to link up with each other that resulted in the extraordinary event we know as May '68. But, and this is Ross's main point, none of these groups -- students, workers, farmers, etc. -- can be treated as pre-existing, self-contained, homogeneous entities. As for the encounters between these heterogeneous groups, they obviously cannot be treated in the same way that one might regard the actions of states agreeing by treaty to work together for the sake of a common interest. Ross suggests that the process might better be described as 'cultural contamination' and argues that it 'was encounters with people different from themselves -- and not the glow of shared identity -- that allowed a dream of change to flourish'. Ross's purpose, however, is not to assert the primacy of the individual, or indeed the primacy of differences, two moves which as [Fredric] Jameson has shown in his various critiques of Anglo-American cultural studies lead inexorably to political paralysis. By repudiating both the collective and the same under the utterly misconceived banner of 'anti-totalization', cultural studies has for all practical intents and purposes divested itself of two of the most basic prerequisites for politics, namely the potential for a common action and the identification of a common aim. Well aware of the pitfalls of valorizing the individual at the expense of the collective, the different at the expense of the same, Ross argues for an approach to the sociological dimension of May '68 that is perfectly attuned to Deleuze and Guattari's work.

Buchanan, Ian. Deleuze and Guattari's Anti-Oedipus. NY: Continuum, 2008: 13-19.

Monday, July 26, 2010

Toronto Police Arrest Over 600 in Crackdown Outside G20 Summit; Naomi Klein - The Real Crime Scene Was Inside the G20 Summit

(Reports on the June G20 Summit in Toronto, The Protests, and the Police Violence)

Democracy Now

Toronto Police Arrest Over 600 in Crackdown Outside G20 Summit

Canadian police have arrested over 600 people in Toronto in a police crackdown on protests at the G20 summit. Riot police used batons, plastic bullets and tear gas for the first time in the city’s history. More than 19,000 security personnel were deployed in Toronto, and a nearly four-mile-long security wall was erected around the G20 summit site at the Toronto Convention Center. The security price tag for the summit is estimated at around $1 billion. Franklin Lopez of the Vancouver Media Co-op filed this report from the streets of Toronto.

Naomi Klein: The Real Crime Scene Was Inside the G20 Summit

As thousands protested in the streets of Toronto, inside the G20 summit world leaders agreed to a controversial goal of cutting government deficits in half by 2013. We speak with journalist Naomi Klein. "What actually happened at the summit is that the global elites just stuck the bill for their drunken binge with the world’s poor, with the people that are most vulnerable," Klein says.

Journalist Describes Being Beaten, Arrested by Canadian Police While Covering G20 Protest

Among the hundreds of people arrested at the G20 protests in Toronto were a number of journalists. Jesse Rosenfeld is a freelance reporter who was on assignment for The Guardian newspaper of London. He is also a journalist with the Alternative Media Center. He was arrested and detained by Canadian police on Saturday evening covering a protest in front of the Novotel Hotel.

Democracy Now

Toronto Police Arrest Over 600 in Crackdown Outside G20 Summit

Canadian police have arrested over 600 people in Toronto in a police crackdown on protests at the G20 summit. Riot police used batons, plastic bullets and tear gas for the first time in the city’s history. More than 19,000 security personnel were deployed in Toronto, and a nearly four-mile-long security wall was erected around the G20 summit site at the Toronto Convention Center. The security price tag for the summit is estimated at around $1 billion. Franklin Lopez of the Vancouver Media Co-op filed this report from the streets of Toronto.

Naomi Klein: The Real Crime Scene Was Inside the G20 Summit

As thousands protested in the streets of Toronto, inside the G20 summit world leaders agreed to a controversial goal of cutting government deficits in half by 2013. We speak with journalist Naomi Klein. "What actually happened at the summit is that the global elites just stuck the bill for their drunken binge with the world’s poor, with the people that are most vulnerable," Klein says.

Journalist Describes Being Beaten, Arrested by Canadian Police While Covering G20 Protest

Among the hundreds of people arrested at the G20 protests in Toronto were a number of journalists. Jesse Rosenfeld is a freelance reporter who was on assignment for The Guardian newspaper of London. He is also a journalist with the Alternative Media Center. He was arrested and detained by Canadian police on Saturday evening covering a protest in front of the Novotel Hotel.

Democracy Now: The New Pentagon Papers -- WikiLeaks Releases 90,000+ Secret Military Documents Painting Devastating Picture of Afghanistan War

The New Pentagon Papers: WikiLeaks Releases 90,000+ Secret Military Documents Painting Devastating Picture of Afghanistan War

Democracy Now